John Todd was born April 13, 1792 to Henry and Polly (Boyce) Edgar. His parents were of Scotch-Irish descent and resided in Sussex County in southern Delaware, a region originally settled by Presbyterians seeking religious freedom and economic opportunity. Henry was a farmer who learned that better land at lower cost was available in the West, so he moved the household to a farm outside Lexington, Kentucky when John was about three years old.

John Todd was born April 13, 1792 to Henry and Polly (Boyce) Edgar. His parents were of Scotch-Irish descent and resided in Sussex County in southern Delaware, a region originally settled by Presbyterians seeking religious freedom and economic opportunity. Henry was a farmer who learned that better land at lower cost was available in the West, so he moved the household to a farm outside Lexington, Kentucky when John was about three years old.

The family settled in Kentucky within the bounds of Cherry Spring Church but then moved to live within the parish of Mt. Pleasant Church. The Edgars were faithful members of their congregation. He was taught at home by his parents with the assistance of Rev. John Tull as a tutor. More formal studies were directed by John Lyle who mastered an academy in conjunction with his call to the Presbyterian Church in Paris, Kentucky. Lyle had studied with William Graham at Liberty Hall in Virginia before moving to Kentucky.

Edgar then attended Transylvania University but did not graduate. His reasons for not completing studies may have been due to controversy about the teaching of science at Transylvania and concern about its doctrinal direction. James Blythe was a Presbyterian minister and educator at Transylvania but left in 1818 when Horace Holley, a Unitarian, was appointed president. During the years leading up to the Holley administration there was debate between those desiring a liberal arts and science institution, while the Presbyterians and members of other denominations believed a classical curriculum was best with science playing a lesser part. Whatever Edgar’s reason for leaving Transylvania, it did not stop him from heading to Princeton Seminary as a member of the class of 1816. However, neither Edgar nor fourteen of his colleagues finished the requirements for a certificate of completion—only one student received a certificate. These candidates exemplify the challenge faced by the Presbyterian Church as it strived to provide properly and consistently educated ministers to shepherd their churches. One would think Edgar’s lack of certification would have been an impediment to licensure and ordination, but this was not the case. Failing to have a seminary certificate did not stop some presbyteries from ordaining candidates—the lower judicatories were not following the policies of their general assembly. He was licensed by New Brunswick Presbytery then examined for ordination by Ebenezer Presbytery in Kentucky and installed in the Flemingsburg church in 1817. After three years in Flemingsburg that included supplying other small churches such as the one at Millersburg, he accepted a call to the church at Maysville ending in 1827. Edgar’s first two calls were to churches in small communities, but the next call would be in the state capital.

When he began ministry with the Frankfort congregation there was good opportunity for growth because people associated with government were moving into town. The capitol had burned and a new one was under construction just a few blocks from First Church’s site on Wapping Street. Conditions seemed good for the congregation, but since the resignation of the previous minister, Eli Smith, the church had lost several members and all the officers. Edgar had been supplying the church occasionally before the congregation formed a committee to compose a memorial to presbytery requesting assistance and asking that Edgar be appointed the stated supply. He began as full-time supply in 1827. The church continued to appreciate his ministry, so a unanimous vote to offer him a full-time call was issued in March 1829. He was installed in July. The author of the church’s history, W. H. Averill, says that Edgar’s ministry quickly brought unity within the congregation and membership was boosted with sixty new members coming from a time of revival in the fall of 1829. Confirming Edgar’s pulpit skills was a politician that heard him preach in Frankfort. Henry Clay commented, “If you want to hear eloquence, listen to the young Presbyterian preacher at Frankfort, named John Todd Edgar.” Quite a compliment from one whose convincing arguments throughout his career either swayed votes or irritated the opposition because of their engaging and persuasive thrust.

Edgar’s experience serving in two rural churches was shown in his concern for vacant pulpits and poor churches. Averill commented,

During his ministry here Dr. Edgar, under direction of Presbytery, spent a considerable part of the summer and fall months in missionary tours, confirming and strengthening the weak and destitute churches in different parts of the Presbytery. He also preached to the country churches in this vicinity. At that time, the Presbyteries seemed to have exercised a very close watch and paternal care over their weaker and struggling congregations, using regular supplies from the pulpits of the stronger churches for their spiritual nourishment. (p. 70)

Edgar’s work at First Church did not hinder his participation in presbytery’s ministry to churches in need. Henry Clay had appraised Edgar as a speaker, but E. P. Humphrey, a minister and educator, said in The Dead of the Synod of Kentucky that Edgar’s Frankfort years were preparation for his continued ministry and likened his sermons to those of John Chrysostom (347-407) whose facility with language was balanced by concern for clarity for all listeners. It is important for ministers to discern the spiritual needs and educational capacities of the congregation, then contour their messages appropriately. Edgar was particularly gifted in this area. During the six years serving in Frankfort, 158 members were added to the church, the session was established with five elders, nine deacons were chosen to minister to physical needs, and a proper minute book with church records was written. Ministers that preach well are sought by other congregations for their pulpits and ministers that have experience dealing with difficult situations are sometimes needed as well—John Todd Edgar qualified for both and he would use his gifts to help a different church.

First Church in Nashville, Tennessee was hit a heavy blow in January 1832. Pastor Obadiah Jennings died on the twelfth after an extended illness and the church sanctuary burned to the ground on the thirtieth. The congregation quickly planned to resolve both situations. With regard to a minister, Phillip Lindsley, who worked at the University of Nashville, agreed to become interim pastor while the search committee sought a suitable candidate for pastor. A building committee was appointed to acquire an architect and begin construction post haste. After an attempt to call Robert J. Breckinridge from his charge in Baltimore and no interest to adopt his suggestion to call his brother William L. Breckinridge, the call was issued to John Todd Edgar, December 22, 1832. He accepted the call after considerable correspondence with Lindsley about the church situation and updates about the cholera epidemic. The Edgars moved to Nashville and settled in the recently purchased manse as he began preaching in the temporary facility August 4, 1833. Installation was not until December 25 with the sermon delivered by Lindsley from the verse, “For I have not shunned to declare unto you all the counsel of God,” Acts 20:27. Unfortunately, Edgar would not be able to preach in the new church until 1836. The massive building would have a seating capacity of 1200 and a spire towering 150 feet

Just as his ministry began in Frankfort with a revival, such was the case in Nashville, but this revival included the Baptist and Methodist churches. Also, as he had done in Frankfort, the session began keeping minutes, rolls, and other information in a session book. Edgar continued his work with the presbytery, often supplied churches without ministers, and was involved with parachurch ministries such as the American Bible Society. But possibly one of the most challenging tasks he would face during his entire ministry would be at the general assembly.

The General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, Old School, convened at 11:00 the morning of Thursday, May 19, 1842, in the Seventh Presbyterian Church, Philadelphia. Retiring moderator Robert J. Breckinridge delivered the sermon from 2 Thessalonians 1:11,

Wherefore also we pray always for you, that our God would count you worthy of this calling, and fulfil all the good pleasure of his goodness, and the work of faith with power.

Following Breckinridge’s prayer, the enrollment of commissioners, and other business, Edgar was elected the new moderator. He did not know it when he grasped the gavel, but the assembly would end June 4 after 15 days of sessions. Among some of the issues addressed were receiving a report from the Standing Committee on Psalmody which included distributing to the commissioners 200 copies of the committee’s proposed book of hymns. Later, a motion was made to adopt the book, but another motion proposed removal of some hymns and editing others. Motions for editing additional hymns continued until Charles Hodge moved the proposed hymnal be returned to the committee, revised as needed, and then resubmitted to the next assembly.

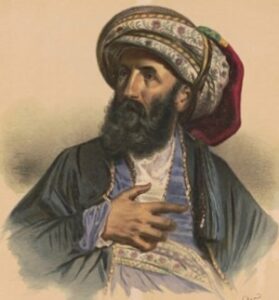

Then there was a curious motion from R. J. Breckinridge, curious because it seems out of line with his Old School subscription to the Westminster Standards. He moved that Mar Yohannon, a bishop of the “Nestorian Christians” of Ooromiah (Urmia) in Persia visiting the United States “be invited to sit with the Assembly; that a seat be provided for him near the Moderator; and that the Moderator invite him to address the Assembly, at such time as may suit his convenience.” Breckinridge was a member of the Board of Foreign Missions which had been working with the Nestorians because Yohannon was unusually receptive to the Old School’s involvment. The motion passed, and Mar Yohannon with American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) missionary Justin Perkins were seated in the assembly. The Nestorian bishop spoke to the confessional Presbyterians. What is curious about this is that Nestorius (d. 451) understood the person of Christ as not only having two natures but two natures manifest in two persons, one human, the other divine. The understanding of Nestorianism at the time of the Assembly was based on secondary sources written in opposition to Nestorius’s view. It was not until the end of the nineteenth century that documents writen by Nestorius were discovered to provide a primary source. Nestorious’s view was condemned as heresy by the Council of Ephesus in 431. The Westminster Confession, 8:2, says about the person of Christ that,

Then there was a curious motion from R. J. Breckinridge, curious because it seems out of line with his Old School subscription to the Westminster Standards. He moved that Mar Yohannon, a bishop of the “Nestorian Christians” of Ooromiah (Urmia) in Persia visiting the United States “be invited to sit with the Assembly; that a seat be provided for him near the Moderator; and that the Moderator invite him to address the Assembly, at such time as may suit his convenience.” Breckinridge was a member of the Board of Foreign Missions which had been working with the Nestorians because Yohannon was unusually receptive to the Old School’s involvment. The motion passed, and Mar Yohannon with American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) missionary Justin Perkins were seated in the assembly. The Nestorian bishop spoke to the confessional Presbyterians. What is curious about this is that Nestorius (d. 451) understood the person of Christ as not only having two natures but two natures manifest in two persons, one human, the other divine. The understanding of Nestorianism at the time of the Assembly was based on secondary sources written in opposition to Nestorius’s view. It was not until the end of the nineteenth century that documents writen by Nestorius were discovered to provide a primary source. Nestorious’s view was condemned as heresy by the Council of Ephesus in 431. The Westminster Confession, 8:2, says about the person of Christ that,

the Godhead and the manhood, were inseparably joined together in one person, without conversion, composition, or confusion. Which person is very God and very man, yet one Christ the only Mediator between God and man.

It appears the assembly was simply showing hospitality to the bishop because of his enthusiastic cooperation with the Board of Foreign Missions, but it could easily have been misunderstood, particularly in light of the Confession. During the first centuries of church history many churchmen labored to define precisely the person and work of Christ as well as the doctrine of the Trinity; the Nestorian heresy was contrary to fundamental, basic theology. However, denominations founded by individuals or groups holding to a defining doctrine sometimes advance in Bible knowledge and find their distinctive view is clearly incorrect and since the view is fundamental to the denomination’s identity, it is downplayed but not abandoned. Maybe the Nestorinism of Nestorius was on the back burner and the Board of Foreign Missions believed it could work with Yohannon (see Notes for more information). However, it seems that by the end of the nineteenth century the Russian Orthodox Church was predominant.

One case before the assembly involved the marriage of Rev. Archibald McQueen to his deceased wife’s sister. McQueen had appealed the decision of the Presbytery of Fayetteville in North Carolina disciplining him for the marriage. McQueen was not in attendance to present his case but a commissioner was appointed to represent him. Several motions were brought with considerable debate, delays, and even a proposal to revise the Westminster Confession. The case would remain on the assembly’s docket for a few years because of appeals and overtures from presbyteries. Read the biography “Archibald McQueen, 1796-1854” for further information.

As the sessions continued, the Bills and Overtures Committee presented Overture 12 concerning ordination. The assembly adopted the committee recommendation.

A communication from the Presbytery of the Western District, on the subject of allowing ruling elders to unite in the imposition of hands in the ordination of bishops [ministers]. The committee unanimously recommended an adherence to the order, and until recently, the uniform practice of our Church on this subject, viz. to allow preaching elders or bishops only to engage in that service.

This action by the assembly shows the growing influence of the two-office view, elders and deacons, compared with the existing three office view including bishops/ministers, ruling elders, and deacons. Elders in the two-office view have two functions—teaching elders that administer the word and sacraments as members of presbytery, and ruling elders that rule as shepherds and are members of the congregations. This topic would be debated during the subsequent years with the two-office view being adopted by the Southern Presbyterians, and the three offices would continue in the PCUSA.

Overture 18 on slavery as reported by the Bills and Overtures Committee was tabled. A motion to take up the slavery overture was lost, but then it was referred to the next General Assembly.

A stellar group was appointed to the Standing Committee on Commemoration of the Westminster Assembly [Bicentennial]. The committee included assembly moderators past and future, R. J. Breckinridge, John M. Krebs, Charles Hodge, Drury Lacy, George Howe, Benjamin M. Smith, and William W. Phillips, who were joined by three other ministers Alexander Macklin, William Chester, and Robert Stuart. The lack of ruling elders on special committees was not unusual in the era and it is indicative of a hierarchical understanding of the ministerial office.

As the assembly neared its end, John T. Edgar, Archibald Alexander, Henry A. Boardman, R. J. Breckinridge, William Neill, and William M. Engles, among others, were appointed to the Board of Foreign Missions. The Board had been recently formed by the Old School to directly oversee the mission work of the church. Before the division of 1837 missions had been operated by parachurch organizations such as the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM).

The assembly adjourned sometime in the afternoon of June 4. The next assembly would convene at 11:00, Thursday, May 18, 1843, “in such place in the city of Philadelphia as shall be designated by the Stated and Permanent Clerks.” Attempts to have the assembly somewhere other than Philadelphia had, once again, failed. The site chosen was Central Presbyterian Church. Edgar was not present, so R. J. Breckinridge filled in for him using Acts 15:14, “Simeon hath declared how God, at the first, did visit the Gentiles, to take out of them a people for his name.”

Unbelievably, First Church burned down again and Edgar would have to lead the congregation through another building program. The Nashville Union, Friday, September 15, 1848, reported that a fire began on the roof of the church as the result of some repair work being done. The flames were enabled by wind to jump the streets and eventually consume three houses. The new church was built in the Egyptian Revival style outside, but the interior was austere until sometime after the Civil War when it was remodeled to conform to the Egyptian style. The church was dedicated Easter Sunday, April 20, 1851, and it is currently the building in use by Downtown Presbyterian Church (PCUSA).

One aspect of Edgar’s ministry in Nashville was his association with President Andrew Jackson. After his second term ended in 1837, seventy-year-old Jackson retired to his plantation called Hermitage located about a dozen miles from First Church. Jackson and some other locals had built a small church on his property in 1824 that was initially called Ephesus Church until 1840 when it became Hermitage Church and a member of Nashville Presbytery. An account of Jackson’s religious life is provided in James Parton’s biography. While Jackson was in office he believed he should not commit to a particular church. He promised his wife, Rachael, who died in 1828, that once he retired he would join a church. Within a few years of Jackson’s retirement, Edgar conducted a series of revival meetings at Hermitage Church. Jackson attended all the meetings and on the last day Edgar delivered a sermon on God’s providential direction in human affairs. The subject had always interested Jackson and it engaged his attention. After the service, he asked Edgar to visit him, but he could not do so until the next morning. That night as he anticipated Edgar’s visit Jackson was restless as he continued pondering the sermon. When Edgar arrived and heard Jackson express his unrest he inquired about his understanding of the fundamentals of doctrine, presumably topics such as Christ’s work, repentance, and faith, which were answered correctly. But then one last question was asked, “General, can you forgive all your enemies?” After some thought he said he could forgive his political enemies. But Edgar persisted saying that all enemies must be forgiven. Further thought eventually brought him to say he forgave all his enemies. Soon thereafter he joined the Hermitage Church according to Parton’s account. When Jackson died June 8, 1845 the funeral service was held a few days later on the grounds of the Hermitage. Estimates set the crowd at about 3,000 people that gathered on the lawn for the service. Pastor Edgar’s Bible text was, “These are they which came out of great tribulation, and washed their robes white in the blood of the Lamb” (Rev. 7:14). He was buried next to Rachel in a tomb on the Hermitage property. Jackson’s mother had prayed that he would become a Presbyterian minister, but he did die in the Lord and spent his last years as a member in good standing of Hermitage Church.

John Todd Edgar died unexpectedly of a stroke November 13, 1860. He had served First Church for 27 years and the day before he died he delivered his last sermon. He was so important to and so loved by Nashvillians that by proclamation of the mayor there was a suspension of business and the court was adjourned to mourn his loss. His first marriage was to Mary Todd, daughter of Dr. Andrew Todd. Their children included Samuel Miller Edgar who died in 1845 while studying at Princeton Seminary. Two of his sons and daughters survived him. His second wife was a widow named Ann (Morris) Crittenden and she survived him. Honors given Edgar include being moderator of the Synod of Kentucky in 1831 and an honorary Doctor of Divinity. When Danville Theological Seminary was organized he was one of the directors and served as chairman until his death. Joseph Bardwell was Edgar’s co-pastor (term used in the source) and he delivered the memorial. Unfortunately, Pastor Edgar cannot be assessed regarding the content of his well-delivered sermons because this writer could not locate any. He delivered his sermons from memory, so it makes sense that without a stenographer to take down his messages, they could not be published. He edited a newspaper briefly and may have written some articles for that publication. It was common in the era for newspapers to sometimes publish the local minister’s sermons, so some searching might find some of his sermons.

Barry Waugh

Notes— The header shows a map of Nashville in 1877. First Church is marked with a red ellipse and the capitol, which was completed the year before Edgar died, is marked with green. Both the map and the picture of Bishop Mar Yohanna, dated 1842, are from the Library of Congress digital collection. The Middle East became a significant mission field for the PCUSA, see the articles on this site, “Shushan Wright, died 1890,” tells about a murdered national who was married to an American missionary, and “Samuel G. Wilson, 1858-1916,” tells of Armenian missions.

For more about Mar Yohannon and the Old School, see Kaley M. Carpenter, “Presbyterianism in the Middle East,” in The Oxford Handbook of Presbyterianism, editors Gary Scott Smith and P. C. Kemeny, OUP, 2019; the section, “Presbyterianism and Persian Nationalism in Urmia: A Case Study,” pages 199-204, is informative.

Sources include J. Thomas Scharf, History of Delaware, 1609-1888, 2 vols, Philadelphia: L. J. Richards & Co. 1888. For the Henry Clay quote see its use in Joseph M. Wilson, The Presbyterian Historical Almanac and Annual Remembrancer of the Church, 1862, page 87. James Parton’s biography is Life of Andrew Jackson in Three Volumes, vol. 1-mother’s influence, vol. 3-church experience, were used, New York: Mason Brothers, 1860.

Sources used for Edgar’s Kentucky years include Robert Davidson, History of the Presbyterian Church in the State of Kentucky; with A Preliminary Sketch of the Churches in the Valley of Virginia, New York: Robert Carter, 1847; Louis B. Weeks, Kentucky Presbyterians, Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1983; and W. H. Averill, A History of the First Presbyterian Church, Frankfort Kentucky Together with the Churches in Franklin County in Connection with the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, Cincinnati: Montfort & Co., 1901. Also, E. P. Humphrey, The Dead of the Presbyterian Church, in Kentucky, Address Delivered before the Two Synods of Kentucky at their Joint Centennial, held at Harrodsburg, October 12, 1883, Louisville: Courier-Journal Job Printing Company, 1883. Robert S. Sanders, Presbyterianism in Paris and Bourbon County, Kentucky 1786-1961, Louisville: The Dunne Press, 1961. Thomas Marshall Green, Historic Families of Kentucky. With Special Reference to Stocks Immediately Derived from the Valley of Virginia [etc.], Cincinnati: R. Clarke, 1889. Kentucky became a state June 1, 1792 and before that was a part of Virginia.

Information about Transylvania University is found in Eric H. Christianson, “The Conditions for Science in the Academic Department of Transylvania University, 1799-1857,” in The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, Vol. 79, No. 4 (Autumn 1981), pp. 305-325; Transylvania University Alumni Directory 1981: Bicentennial Edition; and John D. Wright, Transylvania, Tutor to the West, University Press of Kentucky. The university’s website has a list of its presidents with pictures and brief bits about them.

Sources for information about his Tennessee years include Lindsley’s installation sermon for Edgar in Nashville, “The Pastoral Office and Work,” from The Works of Philip Lindsley, D.D., Sermons and Religious Discourses, vol. 2, Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1866, pages 303-377. Damaris Witherspoon Steele, First Church: A History of Nashville’s First Presbyterian Church, vol. 1, 2004; The First Presbyterian Church Nashville, Tennessee: The Addresses Delivered in Connection with the Observance of the One Hundredth Anniversary, November 8-15, 1914, Nashville: Foster & Parkes Company, 1915; W. F. Creighton, Jr., and L. R. Johnson, eds., The First Presbyterian Church of Nashville: A Documentary History, Nashville: First Church, 1986; Jesse Wills, The Towers See One Hundred Years: The Story of the First Presbyterian Church Building, [1951]; William States Jacobs (son of William Plumer Jacobs) wrote for the Ministers’ Alliance of the Presbyterian Church in Nashville an account of local Presbyterianism that was published as Presbyterianism in Nashville, A Compilation of Historic Data, Nashville: The Cumberland Press, 1904; and Joseph Bardwell, et al, Tribute of Respect to the Memory of Rev. John Todd Edgar, D.D., Pastor of the First Presbyterian Church, Nashville, Tennessee, Nashville: Published by the Church, 1860. A memorial for Edgar is in The Presbyterian Historical Almanac and Annual Remembrancer of the Church, Philadelphia: Joseph M. Wilson, 1862, pages 86-87. The addresses delivered at the Tennessee Exposition on Presbyterian Day, October 28, 1897, were published as Pioneer Presbyterianism in Tennessee, Richmond: The Presbyterian Committee of Publication [PCUS], 1898; the event included among its participants ministers James I. Vance, Walter W. Moore (future president Union Seminary, Va.), and G. B. Strickler.