I begin to note down and arrange some recollections of my past life, for the gratification of my children and other friends when I am gone; and also, for the purpose of celebrating the goodness of Divine Providence towards one who was exposed, from early childhood, to the hardships of orphanage, and the temptations of the world, and who, without earthly guardian vested with authority, was left to follow the propensities of a wayward and depraved heart. Truly, “a Father of the fatherless, and a Judge of the widows, is God, in his holy habitation.”

I begin to note down and arrange some recollections of my past life, for the gratification of my children and other friends when I am gone; and also, for the purpose of celebrating the goodness of Divine Providence towards one who was exposed, from early childhood, to the hardships of orphanage, and the temptations of the world, and who, without earthly guardian vested with authority, was left to follow the propensities of a wayward and depraved heart. Truly, “a Father of the fatherless, and a Judge of the widows, is God, in his holy habitation.”

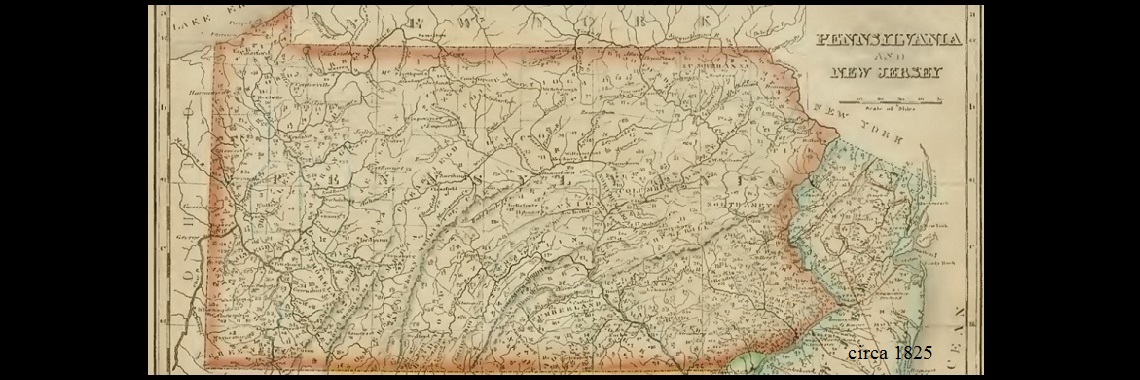

William’s father, likewise named William, and mother, Jane (Snodgrass) Neill, were born and raised in Chestnut Level, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. William was of Irish descent; one branch of Jane’s ancestry was Scottish. The year before the American Revolution the Neills and their children Dorcas, Mary, John, and Jane moved west to Allegheny County and purchased two farms with each on opposite sides of the Monongahela River just a few miles from Fort Pitt. In their new residence the Neills added two children—William and his youngest sister, Margaret. He was born April 25, 1778. The frontier was a difficult place to live not only because of the depravations of such isolated living, but also because the local Indians sometimes raided farms and villages. When the settlers observed signs of an impending raid, they would grab their muskets and head for the local block house. William’s father and his uncle Adam were killed by a raiding party when they went out to check the horses one day. Will’s mother perceived the danger and grabbed him in her arms and led the other children to the block house about a mile away. The loss of his father left his mother with the challenge of raising six children alone. William’s mother died when Will was about four years old. Left an orphan, he was taken in by his uncle Robert Snodgrass who lived a few miles south of Pittsburgh. William commented on the time he lived with his uncle:

I passed six years of my boyhood, in a manner by no means favorable to intellectual or moral improvement, doing light work on the farm, and attending a common country school, at the distance of two or three miles. I used to be terribly afraid of wolves, bears, and panthers in passing to and from school, there being great numbers of those ferocious animals prowling about the rugged hills and dense forests in that part of the county. Deer, wild turkeys, pheasants, quails, and various other species of game were also very abundant and constituted an important item in the provision of most tables.

Uncle Robert and his household were not regular attenders of worship. William had no remembrance of attending church with his aunt and uncle during his six-years under their care. He left their home and went to live with his oldest sister, but he then tired of the arrangement and simply wandered away on his own except for “the unseen and unheeded guardianship of Divine Providence.” He bounced from house to house but was able to pick up a smattering of reading and enough ciphering to become a clerk in a store. The owner was John Daily, but despite his kindness to William, he took another clerk’s job about 1795 in a store in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania. One night he attended a dance and when heading home it rained and he was soaked to the skin. William became very ill. He called on God to heal him promising he would repent, but once he recovered, the ways of the past continued. Despite his return to old habits, he attended the near-by church pastored by Rev. Dr. John McMillan. McMillan was “a very faithful and alarming preacher and aimed directly at the heart and conscience.” Will adds that sometimes he found McMillan troubling.

He made me angry, and I felt tempted to quit hearing him; but, upon the whole, I began to find out, under his preaching, that I was a sinner, and that it was indeed a fearful thing to be in a state of condemnation with the wrath of God abiding on me. His manner was rough, and rather repulsive.

At this time Neill became acquainted with some youths who picked up on his interest in Christ and invited him to their Bible study and prayer meeting. Will began reading his Bible and praying with them. Through Scripture, fellowship with the church, and the sometimes objectionable sermons of Pastor McMillan, he became a communicant member of the church and about the same time believed he was called to the ministry. His hit and miss bits of education received throughout his early years left him at the age of nineteen starting the study of Latin at the local academy in 1797. It was quite a humbling and ambitious step for one his age to start formal studies with the hope of attending college and studying for the ministry. Some candidates for the ministry in Neill’s day were licensed or even ordained by the age of nineteen or twenty.

After a few years of work in the academy he was ready to take the next step. The fall of 1800 he and his friend John Boggs mounted their horses and headed for the College of New Jersey located over three-hundred miles east. Samuel S. Smith was president at the time and he along with the other faculty members examined the boys for admission. Boggs qualified for the junior class, but Neill was assigned to the sophomore class. Neill felt he had been placed too high and struggled to keep his head above water, but the issue that troubled him most was the rebelliousness and impiety of many of his classmates. For example, in March 1802 while some students were gathered waiting for dinner they egged-on a servant to ring the bell in Nassau Hall. While in the belfry the servant inadvertently started a fire that spread consuming the contents of the building leaving only the walls. Such rebellion in colleges of the day was not uncommon and it challenged institutional leaders throughout the nation. Another problem for Neill was the cost of education. During his senior year tuition “amounted to more than a hundred dollars.” In order to pay the bill, he took on work tutoring students. His persistence paid off because he graduated September 1803. To pursue the ministry Neill needed a theological tutor and the pastor of the Princeton Presbyterian Church, Henry Kollock, directed his studies. October 3, 1805, he was licensed to preach by the Presbytery of New Brunswick after examination and delivery of his sermon from Galatians 6:14. Just two days later he married Princeton resident Elizabeth Van Dyke. The couple moved to Cooperstown, New York, where William supplied the pulpit recently vacated by Rev. Isaac Lewis. After about a year he was called to pastor the church and was installed by the Presbytery of Oneida in November 1806.

While Neill worked in Cooperstown the church built a new sanctuary and he and Elizabeth had two children named William Van Dyke and Elizabeth. After only a few years of stable and faithful ministry he accepted a call to the First Presbyterian Church of Albany in the summer of 1809 where he succeeded John B. Romeyn. As Neill packed up the family’s worldly goods and prepared to move sixty miles east to Albany, he delivered a farewell sermon from 2 Corinthians 13:11, “Finally, brethren, farewell; be perfect, be of good comfort, be of one mind, life in peace; and the God of love and peace will be with you.” It was an encouraging passage to preach as the Neills anticipated their new home while remembering fondly the Cooperstown congregation.

The move to Albany did not begin well. Just a few weeks into his tenure Elizabeth became severely ill and died November 12, 1809 leaving two infants with the youngest but five months old. A nanny was hired to take care of the children as Neill continued his work. Among his ministries in Albany were the institution of a Bible class; assisting the establishment of Second Presbyterian Church with Rev. John Chester its first minister; and he became a leader in local parachurch ministries. In 1811 he-married Frances King. Neil also worked in the courts of the Presbyterian Church and was elected moderator of the General Assembly in 1815. From the perspective of his autobiography as Neill looked back on the Albany years, he regretted spending too much time in his study preparing sermons and not enough time with the congregation. Once again, though, Neill did not stay in his call for long.

During the summer of 1816 he received a call from Sixth Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia. Sixth had recently been formed by a group that left Third Church (Old Pine Street). But once again things did not get off to a good start. First Presbyterian Church had grown greatly and needed a larger church, but available property in the heart of the city was limited resulting in the purchase of a lot within a square of Sixth Church. When the building was completed a sizeable group who attended Sixth chose to go to the new First Church. Neill said the “good understanding between the two churches was not essentially disturbed by this occurrence,” and Sixth Church was “not disposed to complain of this as a grievance, but we felt it a hindrance to our increase.” Even though Neill downplayed the situation, it is clear he and his congregation did not think First Church’s action appropriate. It was perceived as a case of building on another man’s foundation (Romans 15:20) and it made ministry difficult for Neill. However, despite the tension with First Church he had a fruitful ministry that included a large Bible class for women and another one with the youth. He catechized the children with the Westminster Shorter Catechism once a month and visited families as he could. In conjunction with his work for Princeton Seminary as a director (1812-1860) and fund raiser he formed The Phoebean Society which included women who supported the seminary with general funds and provided scholarships for ministerial candidates in need. It was during this time that Union College gave him the Doctor of Divinity in 1821. Pastor Neill had been in Philadelphia for eight years when his ministerial direction would enter a new field but not one that was outside his interests.

Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, recently had its president, John M. Mason, resign and Neill was sought for the position. After some wrestling with the shift from pastoral to educational-administrative work, he accepted the opportunity and left Sixth Church for Carlisle, September 1824. When Neill arrived at Dickinson, he found his “new scene of labor…in rather a low and unpromising plight.” Mason’s health had been poor while he was president and the two years of his tenure produced little improvement in the college. Neill resolved to do his best to improve the college by increasing enrollment and raising funds. His goals suffered a setback the first winter because he was sick in bed, but when he recovered funds were raised and during his tenure the enrollment doubled. It is not uncommon for faculties and their governing boards to have strained relationships and this was the case at Dickinson. Neill thought the trustees were too involved in the day-to-day operations and discipline of students. Neill left the college with some of the faculty in 1829 and his successor, Samuel B. How, likewise faced challenges leading to Dickinson’s closure in 1832. It was not a wonderful experience for Neill, but for a few years of his leadership things were on the mend for Dickinson.

After commencement at the end of September 1829, Neill was without a job because the College closed in the wake of the faculty exodus. His next position was as Corresponding Secretary and General Agent of the Board of Education of the Presbyterian Church. Neill found this a difficult and unfruitful work which was complicated for him by health issues. He stayed in the position for only two years. John Breckinridge was his successor. Neill continued to be interested in the work of the Board of Education and was appointed to it by the General Assembly for many years.

The next ministry for Neill was as stated supply to the Presbyterian Church in Germantown which was not far outside Philadelphia at the time. Germantown is named for the German immigrants that settled there in the eighteenth century. The Germantown Church was a poor congregation which explains why he remained a supply for eleven years; the congregation could not pay him sufficiently. Neill commented on what the situation was like.

When I entered that uninviting field, the church had but a nominal existence. There were three ruling elders, with one deacon, and a few communicants, hard to find, scattered and disheartened. I looked after them, and found that several, whose names were enrolled, had died or moved away. I preached to the few that could be collected, twice on the Sabbath, lectured on Wednesday evenings, and opened a rotary prayer-meeting on Friday evenings; and thus, we moved on very slowly, but harmoniously. I introduced the keeping of sessional records, which was a new measure there; as they had not been used to anything more than a register of members, admissions to the Lord’s table, baptisms, marriages, and deaths. It was a day of small things, yet we grew by little and little, with ebbings and sowings; for the population was sparse and fluctuating. Presbyterianism was at a ruinous discount, and materials for a church of that name very scarce. The few churchgoing people in and about the town were Lutheran, German Reformed, Methodist, Episcopalians, Mennonites, &c.

The challenging situation was complicated further by the death of his wife Frances October 13, 1832. He married his third wife, Sarah S. Elmer, April 15, 1835. Pastor Neill worked faithfully in the church and enjoyed a revival at one point resulting in a dozen or so individuals becoming communicant members. At his suggestion a church library was developed to encourage reading good books. When he left the church in 1843 it maintained its ministry and ten years later under the leadership of Henry J. Van Dyke it was a self-sustaining church.

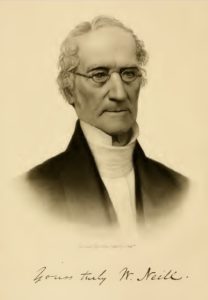

When Dr. Neill left Germantown it was to retire from full time pastoral responsibilities but not from ministry. He supplied a variety of pulpits and preached nearly every Lord’s Day. Charitable institutions such as the Widow’s Asylum (a residence for poor widows) were on his visitation list as well as hospitals and orphanages. He also found time to deliver lectures on the evidences of Christianity twice, and he published Lectures on Biblical History: Comprising the Leading Facts from the Creation to the Death of Joshua (1846), and Practical Exposition of the Epistle to the Ephesians in a Series of Lectures Adapted to be Read in Families and Social Meetings (1850). Included in Autobiography of William Neill, D.D. are a memorial message by the book’s editor, J. H. Jones, and fourteen of Neill’s sermons including ones titled, “Enoch’s Walk with God,” “The Conversion of Saul of Tarsus,” and “Choose Whom Ye will Serve.” William Neill passed away August 8, 1860 after 82 years of providential direction by God from life as an orphan to ministry and membership in the Kingdom of God. Jones says of Neill’s death, “it was so gentle that the exact moment was not perceived.”

Barry Waugh

Notes—The paragraph quoted at the beginning of this biography is from the preface of Neill’s autobiography. The portrait is the frontispiece of his autobiography. Some information about Dickinson College is from the website of the college.