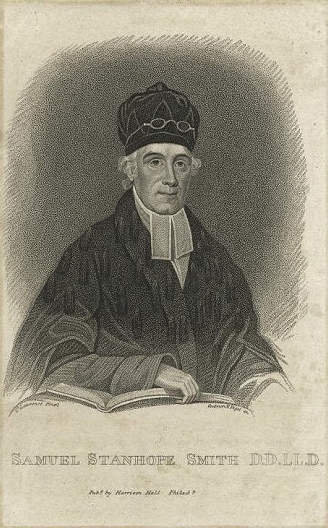

The image of Samuel Stanhope Smith shows him in his later years. Archibald Alexander described his impressions of Dr. Smith when they first met at an earlier time in his tenure at Princeton College.

The image of Samuel Stanhope Smith shows him in his later years. Archibald Alexander described his impressions of Dr. Smith when they first met at an earlier time in his tenure at Princeton College.

I had met Dr. Samuel Stanhope Smith in Philadelphia, six or seven years before; and certainly, viewing him as in his meridian, I have never seen his equal in elegance of person and manners. Dignity and winning grace were remarkably united in his expressive countenance. His large blue eye had a penetration which commanded the respect of all beholders. Notwithstanding the want of health, his cheek had a bright rosy tint, and his smile lighted up the whole face. The tones of his elocution had a thrilling peculiarity, and this was more remarkable in his preaching, where it is well known that he imitated the elaborate polish and oratorical glow of the French school. Little of this impression can be derived from his published discourses, which disappoint those who do not know the charm of his delivery. On this occasion, Dr. Smith appeared to great advantage, for though he had passed his acme, he was erect and full of spirits. The formality used in the collation of degrees does not appear to be of much importance, but with the sonorous voice and imposing mien of President Smith, it added dignity to the scene, and left an indelible impression.

In Smith’s last years Alexander said of him that he was “tall, slender and feeble, but erect,” and that until his death, he was noted for “the eloquence of his pulpit discourses, and for the matchless courtliness of his manners.”

The infant Samuel Stanhope Smith who would mature to be the gentleman described by Alexander, was born March 16, 1751 in Pequea, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Pequea is a bit over twenty miles east southeast of York on the east bank of the Susquehanna River. His father was a Presbyterian minister named Robert Smith who had entered the colonies from Ireland, pastored a church, and operated an academy he established. His mother was Elizabeth, the daughter of Reverend Samuel Blair, and she was the sister of two ministers of the Faggs Manor Presbyterian Church, Samuel and John Blair. Samuel Stanhope showed remarkable intellectual gifts like his brother John Blair Smith. When only six or seven years old he began studying the classical languages in his father’s school. The only language spoken in the school was Latin and whoever uttered a word in the vernacular was rebuked. Young Samuel made the best of his educational opportunities in the academy and made full use of his father’s fine library. He worshipped with his family in his father’s church and listened attentively to the sermons. It was said that he could reiterate a considerable portion of a sermon at its conclusion when asked to do so. The apple did not fall far from the tree because Samuel was interested in becoming a minister. As a lad he would sometimes gather his brothers and sisters into a congregation, then he would be the minister and lead his siblings through worship.

Young Smith was sent to Princeton for his college studies. His student years in the college began just after the death of President Samuel Finley in 1766 and then continued for a few years into the tenure of John Witherspoon. He entered Princeton with the junior class just like his younger brothers John Blair and William Richmond would do in a few years. At the age of eighteen he received the Bachelor of Arts then returned to Pequea to assist his father in the academy while he continued his own studies of interest. However, at the invitation of John Witherspoon he returned to Princeton in 1770 to become a tutor in the college. During the time as tutor he was also under Witherspoon’s oversight as he studied divinity in preparation for the ministry. In 1773, Smith was licensed to preach by the Presbytery of Newcastle and then he relocated to Virginia to become a missionary.

When Licentiate Smith arrived in Virginia there was considerable interest within Hanover Presbytery to provide schools for educating the local youth. He concurred with the movement and provided support and encouragement. One of his indirect influences on education was through a student he tutored at Princeton, William Graham, who began an academy in the fall of 1774 that later became Liberty Hall, then Washington College, and is currently Washington and Lee University. Continued concern for schooling resulted in Smith’s appointment, February 1775, to head Prince Edward Academy which would become Hampden-Sydney College eight years later. Also that year, Smith married the daughter of his Princeton mentor, Ann Witherspoon. Parallel to his educational work in the college was pastoral ministry to the Cumberland and Prince Edward congregations. He was ordained and installed on October 24, 1775. Smith wasted no time when it came to adding faculty to the academy. He hired his brother, John Blair Smith; his brother in law, David Witherspoon; and Samuel Doak who had briefly assisted his father in the Pequea academy. It was as if Princeton College had opened an extension in Virginia given the common alma mater of the academy’s faculty and their use of its curriculum program for education. But Smith was not in Virginia very long because in 1779 he returned to Princeton to become its Professor of Moral Philosophy.

Upon arrival in Princeton, however, Professor Smith realized the college was not doing very well. Because of the Revolutionary War’s Battle of Princeton just a few years earlier the campus had been severely damaged. Visitors to the campus today can see damage to an exterior wall of Nassau Hall that was caused by a cannon ball. Also, remnants of two pieces of ordnance decorate the campus in the form of cannons that have been silenced forever with concrete. The college did not have any students and all its operations had ceased. Mainly by the energy, wisdom, and generous devotion of Smith, Princeton was restored and teaching resumed.

Upon arrival in Princeton, however, Professor Smith realized the college was not doing very well. Because of the Revolutionary War’s Battle of Princeton just a few years earlier the campus had been severely damaged. Visitors to the campus today can see damage to an exterior wall of Nassau Hall that was caused by a cannon ball. Also, remnants of two pieces of ordnance decorate the campus in the form of cannons that have been silenced forever with concrete. The college did not have any students and all its operations had ceased. Mainly by the energy, wisdom, and generous devotion of Smith, Princeton was restored and teaching resumed.

President John Witherspoon died in 1794 after an extended period of declining health which included total blindness for his last few years. The obvious choice to replace him was Vice President Smith resulting in his unanimous election by the board. His Oratio Inauguralis (inaugural lecture) was published that same year. By the spring of 1802, the institution was doing well but its success was stymied by a fire that burned the libraries, furniture, and fixtures. All was destroyed except for the charter, the grounds, and the charred walls of brick and stone. The trustees began immediately to reconstruct the facilities. Thanks to a fund-raising tour by Smith through the southern states a considerable amount of money was raised for reconstruction. New buildings were quickly built, several professors were added to the faculty, and the enrollment increased. Smith was appreciated for his leadership and resourcefulness during the reconstruction, and he gained many new friends and supporters for the college.

President Smith put his imprint on Princeton with a curriculum designed to include rigorous content, discipline, and a concern for the students spiritually. His mastery of Latin, Greek, and Hebrew combined with a reading knowledge of French—he did not think he pronounced it well enough to teach it, provided the college with a president who could promote the institution and raise funds one day, and then teach classical subjects with ease the next day. With regard to recruiting students, he conceded New England recruits to Harvard, Yale, Brown, and Dartmouth, but then directed his sights to the youth in the vast land extending from the Hudson River to Georgia and the west.

In the later years of his presidency things did not go so well for Smith. The number of students on campus in the spring of 1807 was considerable, which was a good thing, but one not so good thing was a disciplinary situation that involved the suspension and dismissal of two students. A considerable portion of the student body responded to what they perceived as an injustice and petitioned the faculty regarding the case. The petition was rejected and 126 students were suspended. One thing led to another with some students rioting and breaking doors and windows. There was a takeover of Nassau Hall by club-wielding students resulting in the militia being called in, but when the students stood firm, the militia was discharged to avoid escalation of the situation. Campus buildings were set afire including the total destruction of an outhouse. It was not a good situation for the college and it was a particularly difficult one for President Smith. There was a significant drop in enrollment and by 1812 four professors had left the college. In addition to the administrative problems faced by Smith were questions regarding theological issues. The college had been Presbyterian since its inception as the Log College. Smith was a minister of the Presbyterian Church and some of the Presbyterians believed he was catering to the Episcopalians and seeking their favor. Further, he was challenged by several individuals for his indifference regarding presbyterian polity and for his limited confessional commitment. Among his detractors were the first two Princeton Seminary professors, Archibald Alexander and Samuel Miller.

When conflicts in the college were added to difficulties with the board and his weakened constitution, it was clear that he needed to retire. At the commencement in 1812, Smith tendered his resignation from the presidency and retired to a residence provided by the college. Samuel Stanhope Smith died on August 21, 1819. He was buried by the side of his predecessors in the president’s office of the college. Ann predeceased him April 1, 1817. The couple had nine children, five survived him.

As would be expected, an educator and minister of Smith’s importance was often honored and sought for leadership. For Princeton, he was not only professor and president but also the clerk of its trustees, 1781-1795, and the college treasurer, 1783-1786. The academic progression of his Princeton years includes Professor of Moral Philosophy, 1779-1783, Professor of Moral Philosophy and Theology, 1783-1812, Vice President, 1786-1795, and President, 1795-1812. He was given the D.D. by both Princeton and Yale, and then the LL. D. by Harvard in 1810. He was a member of the American Philosophical Society. With respect to his work in the Presbyterian Church, he was the moderator of the Eleventh General Assembly in 1799, which was the year after his brother John Blair Smith was moderator, and nine years after his father was moderator.

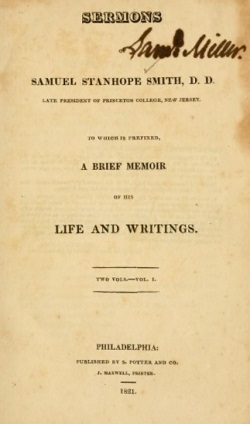

Smith’s publications are numerous and just a selection will be given with their often-lengthy titles abbreviated. In 1795, A Discourse on the Nature and Reasonableness of Fasting was published, and as did so many ministers of his day when George Washington died, Smith delivered An Oration Upon the Death of General George Washington, 1800. The perpetual debate regarding the means and mode of the sacrament of baptism was addressed by Smith in A Discourse on the Nature, the Proper Subjects, and the Benefits of Baptism, 1808. His Lectures on Moral and Political Philosophy, 1812, may be the most important of his publications because he taught moral philosophy for so many years. Sermons on the resurrection of the dead were not so common in his era, so, The Resurrection of the Body: A Discourse Delivered in the Presbyterian Church in Georgetown, 1809, might have induced a few theological descendants of the Sadducees to abandon their skepticism and become supernaturalists. His sermons were published in an edition in 1799, and then in a two-volume set that included a memorial biography in 1821. In Princetonians, W. Frank Craven gave his opinion of Smith’s sermons.

Smith’s publications are numerous and just a selection will be given with their often-lengthy titles abbreviated. In 1795, A Discourse on the Nature and Reasonableness of Fasting was published, and as did so many ministers of his day when George Washington died, Smith delivered An Oration Upon the Death of General George Washington, 1800. The perpetual debate regarding the means and mode of the sacrament of baptism was addressed by Smith in A Discourse on the Nature, the Proper Subjects, and the Benefits of Baptism, 1808. His Lectures on Moral and Political Philosophy, 1812, may be the most important of his publications because he taught moral philosophy for so many years. Sermons on the resurrection of the dead were not so common in his era, so, The Resurrection of the Body: A Discourse Delivered in the Presbyterian Church in Georgetown, 1809, might have induced a few theological descendants of the Sadducees to abandon their skepticism and become supernaturalists. His sermons were published in an edition in 1799, and then in a two-volume set that included a memorial biography in 1821. In Princetonians, W. Frank Craven gave his opinion of Smith’s sermons.

For sermons of a bygone day, these are surprisingly readable. They are neither lengthy, nor burdened by theological abstractions. The literary style is plain and free of oratorical flourishes. One is persuaded to accept the contemporary judgment that Smith knew how to put words in the right place.

BY BARRY WAUGH

Notes—Smith’s birth date is given as 1750 or 1751, I have chosen 1751 in agreement with Noll and Craven; Craven notes that Smith’s grave marker has 1750, but grave marker errors are not uncommon.

Sources— James W. Alexander, The Life of Archibald Alexander, Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1856, is the source for the description of Smith in the first paragraph. Information about the student unrest in 1807 is in the fine book by Mark Noll, Princeton and the Republic: 1768-1822, Princeton University Press, 1989. As with many biographical subjects, the work by William B. Sprague, Annals of the American Pulpit; or Commemorative Notices of Distinguished American Clergymen, volume 3, published in New York by Robert Carter & Brothers, 1858, was consulted. Richard A. Harrison’s, Princetonians: 1769-1775, Princeton University Press, 1980, is nicely done and the Smith article is especially so. Alexander Leitch, A Princeton Companion, Princeton University Press, 1978, includes information on the people, buildings, departments, clubs, societies, traditions, etc., of the university. The General Catalogue of Princeton University, 1746-1906, Princeton: Published by the University, 1908, provides basic information on its graduates through 1906. The first image of Smith is from the New York Public Library free-use online collection.