John Rogers Peale was born to Samuel Alexander and Elizabeth (McIntire) Peale September 17, 1879 northwest of Harrisburg in New Bloomfield, Pennsylvania. He prepared for college in a local academy and professed faith in Christ in the Presbyterian Church at the age of twelve. For college he attended Lafayette in Easton. John was involved in several extra-curricular activities including president of the campus YMCA chapter, membership in the Dramatic Association, a brother of Delta Upsilon fraternity, and editor of the college yearbook. He won the Coleman Biblical Prize his freshman year and graduated Lafayette with honors in 1902.

John Rogers Peale was born to Samuel Alexander and Elizabeth (McIntire) Peale September 17, 1879 northwest of Harrisburg in New Bloomfield, Pennsylvania. He prepared for college in a local academy and professed faith in Christ in the Presbyterian Church at the age of twelve. For college he attended Lafayette in Easton. John was involved in several extra-curricular activities including president of the campus YMCA chapter, membership in the Dramatic Association, a brother of Delta Upsilon fraternity, and editor of the college yearbook. He won the Coleman Biblical Prize his freshman year and graduated Lafayette with honors in 1902.

That fall John moved to New Jersey to study for the ministry at Princeton Theological Seminary. The president of Lafayette College at the time of Peale’s studies was Ethelbert D. Warfield who may have influenced him to go to Princeton given that he was on the board and his brother B. B. Warfield was a professor. Included among his extracurricular activities at the seminary were leading the student band and participating in just about anything related to missions. Demonstrating for all visitors to his dorm room his interest in foreign missions was a large map including annotations for the various fields. Seminary friends commented that when they dropped in to visit John they often found him with an open Bible and in prayer. He was quiet, reserved, and greatly admired by other students and the faculty. John looked out for opportunities to promote world missions by scheduling mission-minded students to fill pulpits in area churches. Before graduating Princeton Seminary in May 1905, he earned a Master of Arts from Princeton University.

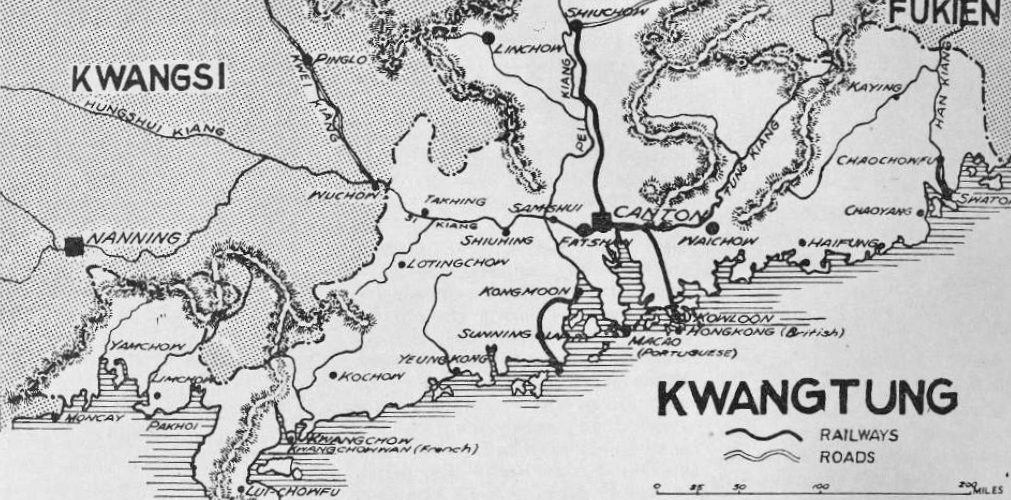

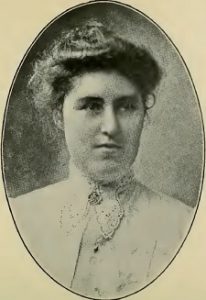

Before he could leave for the mission field there were a few things to do. As a Presbyterian ministerial candidate it was necessary for him to be licensed and ordained by his presbytery. On April 11, 1905, just before he graduated seminary, the Presbytery of Carlisle of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA) licensed him, then just a month later on May 15 he was ordained an evangelist to serve on the foreign field. With his education and ecclesiastical requirements completed before moving overseas, the next step for Peale was marrying Rebecca Gillespie June 29, 1905 in Maryland. Before leaving the port in San Francisco for Lienchou, Kwangtung Province, Rev. Peale expressed hope that he and Rebecca would be allowed to serve the Lord with the Chinese people for forty years.

Before he could leave for the mission field there were a few things to do. As a Presbyterian ministerial candidate it was necessary for him to be licensed and ordained by his presbytery. On April 11, 1905, just before he graduated seminary, the Presbytery of Carlisle of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA) licensed him, then just a month later on May 15 he was ordained an evangelist to serve on the foreign field. With his education and ecclesiastical requirements completed before moving overseas, the next step for Peale was marrying Rebecca Gillespie June 29, 1905 in Maryland. Before leaving the port in San Francisco for Lienchou, Kwangtung Province, Rev. Peale expressed hope that he and Rebecca would be allowed to serve the Lord with the Chinese people for forty years.

At the time the Chinese were transitioning from the ways of the past into the modern world. China had lost the Sino-Japanese war (1894-1895) due to the superiority of Japanese weaponry manufactured with technological guidance from world powers such as Great Britain and the United States. In China, modernization lagged behind the Japanese because of greater resistance to modifying the ancient ways. The Presbyterians and other Western missionaries brought with them not only the gospel and the Bible but different clothing, foods, ways of and media for writing, recreation, and ways of thinking about life. Growing resentment towards foreigners among some Chinese had led to the Boxer Rebellion at the end of the nineteenth century. It is believed that most of the 200 to 250 foreign individuals killed by the Boxers were missionaries, however the greatest death toll was suffered by Chinese Christians with thousands murdered. Not long after the Boxer Rebellion ended, there was an uprising in Paotingfu resulting in the murders of sixteen missionaries and family members including eight from the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions, PCUSA. It was the worst massacre of PCUSA missionaries since killings in India in 1857. The Presbyterians that died included Rev. and Mrs. Frank E. Simcox and their three children, Dr. George Yardley Taylor, and Elsie and Cortlandt Van Rensselaer Hodge, MD, who was the grandson of Charles Hodge’s brother, Hugh Lenox Hodge.

In the few intervening years between the Paotingfu massacre and arrival of the Peales in China, the nation had somewhat stabilized. However, tension was increasing particularly in the larger cities near the coast because of a move to boycott American goods in protest of mistreatment of Chinese immigrants in the United States.

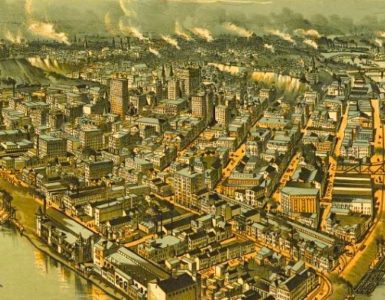

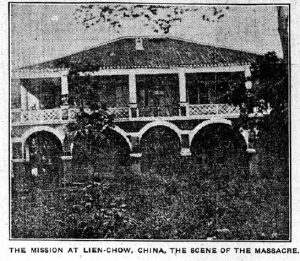

After leaving San Francisco in August, the Peales arrived in Hong Kong by September 28 because John sent a letter thus dated to a friend at Princeton Seminary, A. Lee Wilson. He mentioned to Wilson that the boycott against American goods imported to China was taking hold. He commented that heretofore, “the Americans always enjoyed special favor, and to fly the American flag meant protection; but it is different now,” then he said that no “personal violence has been attempted, but the people are less cordial and more suspicious.” From Hong Kong, the Peales traveled to Canton then continued for about 150 miles up the Pekiang River to the Lienchou River from which they accessed the town of Lienchou. The trip must have been challenging because it took three weeks to complete. When they arrived at the missionary station and were given a tour they saw a sizable campus that included hospitals, separate schools for boys and girls, a recently completed 700 seat church, and several missionary family residences. The Peales were added to the team of Presbyterian missionaries as they anticipated forty years of service.

After all the preparation and a considerable journey to the mission field, John and Rebecca Peale were both murdered by a mob October 28, 1905, after having been there for just four days. Other casualties included several Chinese Christians injured or killed and one missionary, Charles E. Machle, MD, was injured but his wife, Ella, and ten-year old daughter, Amy, were killed. Also killed was Eleanor Chestnut, MD, but another single woman named Patterson survived. Dr. Machle and Miss Patterson had managed to escape the riot by hiding in the office of a local Chinese official. They were fortunate because others were discovered, seized by the mob, tortured, and murdered. When the riot ended, the scene was horrible. The bodies were recovered by Chinese officials and buried by some very sad Chinese Christians.

What had caused the riot?

Dr. Machle had asked some Chinese holding a festival outside the mission hospital to move to a different location. The noise of the celebration was unsettling the patients. There was also a confrontation about some miniature cannons that were fired and it seems they were seized by the missionaries. The cannons were ornate and particularly important to the Chinese for religious or cultural reasons. One thing led to another so that some of the Chinese became aggressive and incited the crowd into a frenzy. In addition to the murders the mob destroyed a considerable portion of the mission compound. The hospitals, missionary residences, schools, and recently dedicated new church were all damaged, destroyed, or burned. The Chinese government responded by sending two gunboats and sixty soldiers along with missionaries and a doctor to the troubled village. Dr. Machle and Miss Patterson were able to be transported by armed guard to Canton for safety. The Chinese government responded further with an imperial edict directing government officials to protect missionaries and their property and pursue, capture, and punish the guilty individuals. Early reports that the riot was incited by Lienchou residents supporting the boycott of American goods were believed to be inaccurate, but certainly a few sympathizers in the crowd could have seen the opportunity for violence against the missionaries.

Dr. Machle had asked some Chinese holding a festival outside the mission hospital to move to a different location. The noise of the celebration was unsettling the patients. There was also a confrontation about some miniature cannons that were fired and it seems they were seized by the missionaries. The cannons were ornate and particularly important to the Chinese for religious or cultural reasons. One thing led to another so that some of the Chinese became aggressive and incited the crowd into a frenzy. In addition to the murders the mob destroyed a considerable portion of the mission compound. The hospitals, missionary residences, schools, and recently dedicated new church were all damaged, destroyed, or burned. The Chinese government responded by sending two gunboats and sixty soldiers along with missionaries and a doctor to the troubled village. Dr. Machle and Miss Patterson were able to be transported by armed guard to Canton for safety. The Chinese government responded further with an imperial edict directing government officials to protect missionaries and their property and pursue, capture, and punish the guilty individuals. Early reports that the riot was incited by Lienchou residents supporting the boycott of American goods were believed to be inaccurate, but certainly a few sympathizers in the crowd could have seen the opportunity for violence against the missionaries.

Thus, hopeful, dedicated, and spiritually zealous Rev. John R. Peale completed seminary, was licensed and ordained, married Rebecca, and with his bride they embarked on a lengthy journey to China only to be murdered in the streets of Lienchou by some of the residents they had hoped to serve. All of this took place within a period of just six months. The Peales four days in Lienchou fell far short of the forty-year ministry that John had anticipated. Murder is always a dreadful crime, after all, it is killing those made in God’s image and is therefore an attack on God himself. The gruesome details of the murders have not been provided in this article because some might find them particularly disturbing and inappropriate. This was a saddening article for the author to write. On November 4, 1905, a memorial service for the Peales was held at Princeton Seminary and their deaths were remembered with a memorial plaque on campus.

Barry Waugh

Notes—The spelling “Lienchou” for the Chinese town was chosen because it was the one most often used, but other spellings include Lienchow, Lien-chou, Lien chow, Lienchau, and on the map in the header, Linchow. Information about Paotingfu is from The Tragedy at Paotingfu, by Isaac C. Ketler, 1902. The excerpt from Peale’s letter to Wilson at Princeton was located in the New York newspaper The Sun, Nov. 5, 1905. Other information was taken from PCUSA General Assembly Minutes and an assortment of period newspapers. A nice China map available online is the Edward Stanford Ltd. Map of China published for the China Inland Mission, London, 1898, as found on the website of the University of North Texas Libraries, University of Texas at Arlington, The Portal to Texas History. The portraits of John and Rebecca are from a magazine clipping that was provided with some letters regarding the Peales by Ken Henke, Special Collections, Princeton Theological Seminary, in December 2016. The photograph of the mission building in Lienchou was found in a religious newspaper of the day. The map image is from Rand McNally Pocket Atlas of the World, 1906.