Drury Lacy was born to William and Elizabeth (Rice) Lacy in Chesterfield County, Virginia, October 5, 1758. William was a farmer whose money management skills were not the best, but despite fiscal challenges, Drury was able to attend a school mastered by an Episcopal priest named McCrea. William died when Drury was about ten years of age leaving the household in a dire financial situation, and the shortage of funds limited his opportunities for schooling. But Drury studied on his own after having to leave McCrea’s school.

One day when Drury was about sixteen, the local militia was drilling while he and some other boys were watching. One militiaman mistakenly overcharged his firearm with powder. He did not want to discharge the weapon so he looked for a volunteer among the crowd of boys, but he did not disclose the potential danger of triggering an over-charged gun. Drury Lacy stepped forward. He grasped the weapon and pulled the trigger resulting in the breach exploding and tearing off his hand. It is difficult to understand why the militiaman knowing the danger of the situation would ask a boy to pull the trigger. The explosive gun problem could have been resolved by wedging it between rocks, tying a cord to the trigger for a lanyard, getting behind a tree, and pulling the cord. Gunsmiths of the day used this technique to test the metal of their barrels before selling their guns. Because of the negligence of the militiaman, Drury Lacy went through life with his stump covered by a silver cup which had a device in which eating utensils and other hand-held items could be clamped for use. Prosthetics are nothing new. As the years passed he came to be called “Old Silver Fist” by some of his less-than-kind peers and later his colleagues in ministry modified the nickname into a more dignified “Lacy with the silver hand and the silver voice.”

After the tragic accident suffered by Lacy matters were compounded by his mother’s death. He needed to support himself fully, possibly siblings too, while trying to complete his hit-and-miss education. He had learned enough to qualify for teaching a school for impoverished children. The wage was limited, but it was income. When the American Revolution started, his handicap kept him from joining the troops, but his teaching work would help the new nation after the Revolution to have citizens with principles built on the common good and the knowledge needed for building a new nation. Education would be important for the Republic.

Lacy found a better paying position teaching the children of Daniel Allen, a Presbyterian elder who served a congregation pastored by John Blair Smith. Smith was struggling to equitably divide his time between pastoral ministry to the Briery and Cumberland congregations while serving as president of Hampden-Sidney College. The college’s first president had been John Blair’s brother, Samuel Stanhope Smith. Drury became a Christian through influences from John B. Smith and the Allen family. His next engagement was teaching the children of Colonel John Nash. Nash was a founding member of the board of Hampden-Sidney College and he fought in the Revolution. One of the advantages Lacy enjoyed because of his friendship with John B. Smith was getting together with him a few hours each week for tutoring in an array of subjects. Drury acquired considerable ability with Latin and Greek and by the age of twenty-three he was a tutor for Hampden-Sidney College; the first one to teach without a formal college education. From the time he became a Christian he had hoped to become a minister and President Smith not only taught him general subjects but also theological studies. Drury Lacy was taken under care of Hanover Presbytery in April 1787 and then licensed in September. He would be ordained in October the following year.

Smith became frustrated with juggling pastoral work and the college presidency and wanted to resign. However, instead he tried for a year to fulfill Hampden-Sidney’s request that he continue in office with Drury Lacy coming on as vice president. Lacy took on some of Smith’s duties to allow him more time for pastoral work and guest preaching, but in 1789 Smith resigned the presidency to dedicate all his time to his congregations. On the 25th of December 1789, Lacy married Anne, the daughter of William Smith of Powhatan County. For several years after their marriage he continued pastoral work supplying churches within the area including a part-time term for Briery Church, 1792-1793, where both the Smiths had ministered. He was also a leader of revival meetings at the Peaks and Pisgah Churches during the communion season and supplied worship services for the churches at Hampden-Sidney College, Charlotte Courthouse, and Buffalo. During the revival at Hampden-Sidney that influenced not only the college but the local people, Lacy worked with Nash Le Grand to bring him to Christ. Lacy was intermittently pastor or supply for Cub Creek Church for about ten years after the Revolutionary War ended. He continued at Hampden-Sidney as vice president (also effectively filling the president’s office) until he left in 1796 to live on a farm that he named Mount Ararat.

There was not an ark on Ararat but there was a classical school started by Lacy where he continued at the lecturn for the remainder of his life. The school was residential with many pupils coming from considerable distances to live with his family or the neighbors while studying. Lacy was known particularly for his ability with Greek and Latin and families chose him to teach their children because of his linguistic skills. Some of Lacy’s students went on to become ministers, lawyers, public servants, and doctors. Just as James Hall was important for North Carolina education, Drury Lacy was influential for Virginia education.

Lacy was often a commissioner representing Hanover Presbytery in the General Assembly and was moderator of the General Assembly in 1809. He was the clerk of Hanover Presbytery for a number of years and was known for his exquisite, flowing, even artistic handwriting.

Drury Lacy was afflicted with a calcification, possibly a gall or kidney stone, which led him to seek medical help in Philadelphia. While there he lodged with an old friend named Robert Ralston. The physicians consulted recommended surgery which was accomplished successfully, but after a few days of improvement Lacy took a turn for the worse and passed away December 6, 1815 at the age of fifty-seven. Anne had stayed home and unbeknownst to Drury she was ill with a fever that led to her predeceasing him. News of her passing was received at Ralston’s but it was withheld from Lacy due to his condition. Drury Lacy was interred in the burying ground of Second Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia. The Lacy’s had six children—three sons and three daughters; two of the sons became Presbyterian clergymen, the third was a physician.

A portrait of Lacy could not be located. Unfortunately, portraits of ministers who died before the development of photography are few in number because painting, engravings, or cameo images were generally expensive and purchased only by those with means to do so. In lieu of a visual portrait, one will be given with words from those who knew him. Anne, the wife of John Holt Rice, knew him when they were children and they continued to be friends as adults. Her letter in remembrance of Lacy is in Sprague’s Annals and she included a quote by Archibald Alexander about him.

His person was very large and imposing and his countenance, when lighted up, was most expressive and delightful. I can in no way bring him more plainly before me, than by remembering him when he was listening with delight to Dr. Archibald Alexander’s eloquence as he gazed with his deep blue eyes over the congregation with tears streaming down his cheeks, to notice the effect which it produced on him. His own preaching was simple and natural, and sometimes very eloquent. His prayers, especially in his latter years, were peculiarly fervent. He seemed, like Abraham, the friend of God, most reverently and devoutly speaking, as if face to face, to his Heavenly Father.…My recollections of him, both in the pulpit and out of it, are most grateful and affectionate.

Archibald Alexander remembered Lacy. The two were often on committees and commissions together for Hanover Presbytery. Alexander observed him often and they were close friends.

His preaching was calculated to produce deep and solemn impressions. His voice was one of extraordinary power. Its sound has been heard at more than a mile’s distance. His voice was not only loud, but clear and distinct. In the largest assemblies convened in the woods, he could always be heard with ease at the extremity of the congregation. On this account, Mr. Lacy was always one of the prominent preachers at great meetings. His preaching was also with animation. His address to his hearers, whether saints or sinners, was warm and affectionate. Indeed, according to his method of preaching, lively feeling in the speaker was an essential thing to render it either agreeable or impressive. Mr. Lacy was therefore a much more eloquent and impressive preacher on special occasions, when every circumstance combined to wind up the mind to a high tone of excitement, than in his common and every day discourses in which he was always evangelical, but sometimes flat and uninteresting. Upon the whole, it may serve to characterize his preaching, to say that it was better suited to the multitude, than to the select few who possess great refinement of taste; better adapted to satisfy and feed the plain and sincere Christian, than to furnish a feast for men of highly cultivated intellect. He enjoyed the unspeakable pleasure of knowing a considerable number of humble, exemplary Christians, who ascribed their first impressions to his preaching or conversation; for he excelled in the art of conversing on the subject of experimental religion. To inquirers and young converts he addressed himself in private in a very happy manner, which was to them often the means of important spiritual benefits. And on general subjects he conversed in an agreeable and instructive manner.

Alexander’s comment that Lacy’s sermons were “flat and uninteresting,” is blunt. It seems that despite Lacy’s “silver voice” his pulpit presentation was not as polished as some listeners desired.

Hugh Blair Grigsby, one of Lacy’s students at the classical school, described Lacy as an imposing and dignified figure.

Above six feet in height, his form a model of the human figure, a dark stern gray eye, and a skin whose olive tints told of his descent from a Norman ancestry, and may still be seen in his descendants; with a self-possession not readily ruffled, and withal, of a pleasing address, and ardently devoted to the duties of his station, he made a favorable impression upon all who approached him. As he walked along, you might suppose him to be a knight who had just descended from the saddle to take his seat in the council.

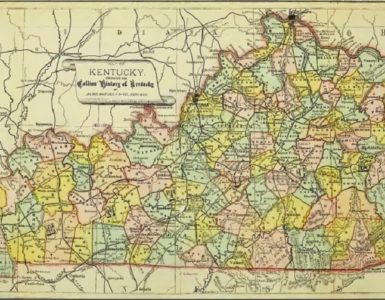

Lacy published A Sermon, Preached on the Occasion of the Death of the Rev. Henry Pattillo: to his former Congregations in Granville County, North Carolina, October 11th, 1801. Sprague mentioned that Lacy published a book on “the great revival in Kentucky and the strange appearances connected with it,” but I could not locate it.

Barry Waugh

Notes—The header image is from Pixabay and it was used on this site several years ago. I could not locate images relevant to Lacy, which may indicate how much he was in the background even though greatly respected and elected General Assembly moderator. The picture of Briery Church in the header was taken by the author several years ago; it is in a remote location accessed by a gravel road (at the time of the picture). In addition to William B. Sprague’s Annals of the American Pulpit, vol. 3, sources used for this post include, A Manual for the Members of the Briery Presbyterian Church, Virginia, compiled by J. W. Douglas and published in Richmond, 1828, it was reprinted in 1971 by Thomas P. Hughes, Jr., Memphis, Tennessee; Encyclopedia of Virginia Biography, volume 2, 152-53, provides a short biography; Bulletin of Hampden-Sidney College, 7:4, January 1913, includes “Centennial Address Delivered June 14, 1876 by The Hon. Hugh Blair Grigsby,” which has an entry for Lacy on pages 21-23; Cub Creek Church and Congregation, 1738-1838, by Elizabeth Venable Gaines, 1931; and William H. Foote, Sketches of Virginia. Second Series, 1856, reprinted by Sprinkle Publications, 2007, has a number of mentions of his name.