Before reading this post, it is suggested that “Philadelphia Centennial, 1876, Presbyterians,” be read for background information.

It had been a long and bumpy road to the Witherspoon statue unveiling with many individuals contributing time and talents. Among those involved planning the memorial in Philadelphia were members of the PCUSA General Assembly Centennial Committee, other individuals from the Synod of Philadelphia, Presbyterian women of the city, the Philadelphia mayor and Pennsylvania governor spoke at gatherings, and architect of the Philadelphia City Hall and Presbyterian deacon, John McArthur, Jr., was consulted for guidance regarding nuances of the statue project.

It had been a long and bumpy road to the Witherspoon statue unveiling with many individuals contributing time and talents. Among those involved planning the memorial in Philadelphia were members of the PCUSA General Assembly Centennial Committee, other individuals from the Synod of Philadelphia, Presbyterian women of the city, the Philadelphia mayor and Pennsylvania governor spoke at gatherings, and architect of the Philadelphia City Hall and Presbyterian deacon, John McArthur, Jr., was consulted for guidance regarding nuances of the statue project.

When it came to help with the Centennial and speakers at the unveiling and associated events, the PCUSA sought to include all aspects of the Reformed and Presbyterian family. For example, Princeton University President James McCosh spoke at the unveiling. An example of kindred denominations participating was the United Presbyterian Church which was represented by Rev. W. W. Barr and ruling elder John Alexander. But the elephant in the kitchen for the PCUSA was the Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS) which from 1861-1865 had been the Presbyterian Church in the Confederate States of America (PCCSA). Many of the Presbyterians in the South had left the PCUSA because of the Gardiner Spring Resolutions which required affirmation of extra-confessional principles that they believed were not within the spiritual ministry of the church. One likely awkward moment during the unveiling occurred when some members of the crowd recognized Stuart Robinson was present. There were calls for him to speak even though he was not on the docket of participants. Robinson was the minister of Second Presbyterian Church, Louisville, and he had been vocal when the War began and after it ended regarding the PCUSA requiring conformity to stipulations contrary to or in addition to the church standards. Shortly after the War, Robinson led several churches in Louisville and the greater Synod of Kentucky from the PCUSA to unite with the PCUS. If there was any one minister the Centennial Committee of the PCUSA did not want to speak, it had to be Robinson. But apparently, the crowd pressure for Robinson to speak was too great for the Centennial Commission leadership to ignore, so he was allowed to discourse briefly at the end of the ceremony. As Robinson spoke, there were surely some Centennial Commission members pulling on their collars, squirming, and grimacing at the Kentuckian’s presence and words. When The New York Times reported the unveiling it listed the leading participants and speakers, but Robinson was not mentioned and the article concluded “the attendance was very large and the exercises interesting.” Nothing is said about how much interest was generated by Robinson’s impromptu speech.

So, if the PCUSA was going to have a PCUS participant, who would it be? The General Assembly almost immediately after the War adopted the requirement that a minister desiring a change of call from a PCUS church to one in the PCUSA had to affirm loyalty to the Federal government, support emancipation, deny the Bible teaches slavery, and repent for siding with the Confederacy. The number of Presbyterian leaders that would have been willing to accept all or even some of the requirements would have limited the selection. Further, if the PCUSA invited a minister who did not affirm the points of the requirement, then it would have transgressed its ministerial transfer legislation for the single-engagement speaker. It was likely a difficult choice to decide who should be invited.

If there would be an official participant from the PCUS, who would it be?

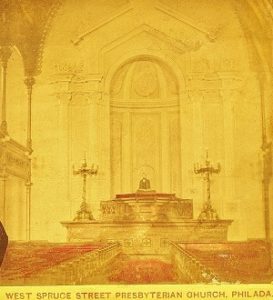

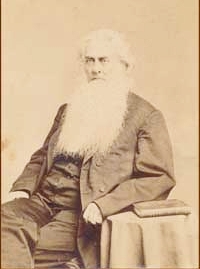

It may be indicative of the trouble answering this question that the PCUSA General Assembly waited until its meeting in May 1876, just five months before the unveiling. The minister chosen to speak was William S. Plumer whose subject was to be the life and works of John Witherspoon. Plumer left his ministry in Baltimore, 1854, to take both a pastoral call to a church and a professorial call to Western Seminary in Allegheny in his home state of Pennsylvania. Beginning in 1862 he supplied churches in Philadelphia and then served in Pottsville before leaving to teach in Columbia Seminary in South Carolina in 1867. During the course of the Civil War, Plumer was a minister of the Old School PCUSA in Pennsylvania, so he did not have some of the sectional issues that other prominent PCUS ministers had. Also, Plumer was the only minister to be moderator of both an Old School General Assembly, 1838, and moderator of a PCUS Assembly, 1871. He was a father of Presbyterians in his era and was greatly respected for his pastoral manner, leadership, and publications in serials, pamphlets, and books. His admirers transcended the sectional divide. On Sunday evening, October 22, Dr. Plumer delivered his Witherspoon lecture in the West Spruce Street Church in Philadelphia (currently, Tenth Church). The faded picture of the church interior accompanying this post shows the pulpit from which he may have spoken.

The text of “John Witherspoon, D.D., LL. D., His Life, Times, and Writings,” that follows was copied from, Witherspoon. Proceedings and Addresses at the Laying of the Corner-Stone and at the Unveiling of the Statue of John Witherspoon in Fairmount Park, Philadelphia, edited by William P. Breed and issued by the Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1877. Plumer’s summary of Witherspoon’s life and works is nicely and concisely done. Note his characteristic use for public events of simple but not simplistic language and an effective combination of short and extended sentences. Even though it is a bit tedious to read and was likely more pleasing when delivered with voice inflection and gestures, the staccato of important personalities in history and their birth dates is effective. There is a brief Latin saying concerning Benjamin Franklin which likely would have been common knowledge for Plumer’s listeners. Even though Witherspoon was distinctively Presbyterian, Plumer’s address does not emphasize his Presbyterianism but instead presents his three-fold life as minister, educator, and statesman for all Americans. Also to be noted is the Civil War had been over just eleven years but there are no sectional or Civil War comments. Plumer was speaking to Americans united for a glorious Centennial occasion to remember Scot-American John Witherspoon. Aging Dr. Plumer recognized the difficulties of the continuing sectional tension, and spoke as a true pastoral and American gentleman with class, character, and compassion. More ministers like Dr. Plumer who can discern difficult situations, interpret adiaphora, stick to their theological guns, yet minister and teach with grace and peace are needed .

The text of “John Witherspoon, D.D., LL. D., His Life, Times, and Writings,” that follows was copied from, Witherspoon. Proceedings and Addresses at the Laying of the Corner-Stone and at the Unveiling of the Statue of John Witherspoon in Fairmount Park, Philadelphia, edited by William P. Breed and issued by the Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1877. Plumer’s summary of Witherspoon’s life and works is nicely and concisely done. Note his characteristic use for public events of simple but not simplistic language and an effective combination of short and extended sentences. Even though it is a bit tedious to read and was likely more pleasing when delivered with voice inflection and gestures, the staccato of important personalities in history and their birth dates is effective. There is a brief Latin saying concerning Benjamin Franklin which likely would have been common knowledge for Plumer’s listeners. Even though Witherspoon was distinctively Presbyterian, Plumer’s address does not emphasize his Presbyterianism but instead presents his three-fold life as minister, educator, and statesman for all Americans. Also to be noted is the Civil War had been over just eleven years but there are no sectional or Civil War comments. Plumer was speaking to Americans united for a glorious Centennial occasion to remember Scot-American John Witherspoon. Aging Dr. Plumer recognized the difficulties of the continuing sectional tension, and spoke as a true pastoral and American gentleman with class, character, and compassion. More ministers like Dr. Plumer who can discern difficult situations, interpret adiaphora, stick to their theological guns, yet minister and teach with grace and peace are needed .

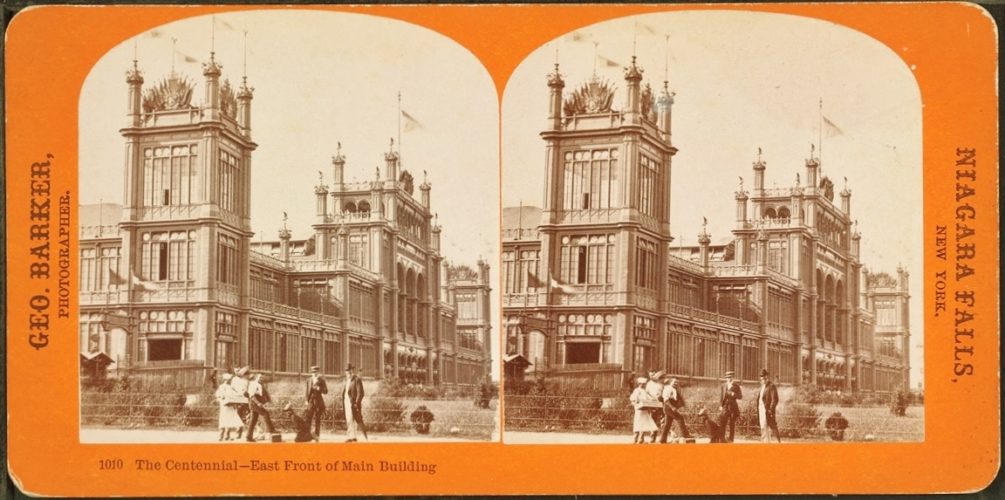

The portrait of Plumer is from the Presbyterian Church in America Historical Center in St. Louis, and the two other images are from the New York Public Library Digital Collection. The header stereoscope view shows one end of the Main Exhibition Building which was just to the left of bronze Witherspoon as he faced the Exposition with the Schuylkill at his back. For information on Robinson and Kentucky Presbyterians see Moore’s Digest, 1898, p. 126ff. In the transcription, a few comments have been made in brackets [ ].

Barry Waugh

Discourse of Dr. Plumer

The whole enterprise received a most fitting climax in the services of Sabbath evening, the 22d of October, when, in the West Spruce Street Presbyterian church, the Rev. W. S. Plumer, D. D., LL.D., of Columbia, S. C, delivered by request of the Centennial Committee of the General Assembly in the presence of a large and intelligent congregation the following eloquent discourse upon the life and writings of Dr. Witherspoon.

John Witherspoon, D. D., LL.D.—His Life, Times, Writings and Services

by William S. Plumer

Most men live and die unknown beyond a narrow circle. Their memory soon fades from earth; but if in this life they walked with God, their record is on high, and in the best sense they shall be held in everlasting remembrance.

A smaller portion of mankind are of low and vicious tastes and habits. They are the tenants of the abodes of infamy and wretchedness. They are led on till they fall into the worst vices and crimes. For fame they have infamy. They have notoriety, but it is with disgrace. Their names rot. They are covered with ignominy.

A still smaller part of the human family rises high in personal worth and accomplishments, in usefulness and honor. They are by Providence favored with good opportunities, and they embrace them. Their names are enrolled among the good, the wise and the great.

Such men are helpful to each other. Like the stars, they are often seen in constellations. The example of one draws many. This remark is illustrated through the eighteenth century. It was ushered in by bright lights, though some of them were great blessings, while others were not. Literature then greatly revived. In many places a marvelous spirit prevailed. Both truth and error, both virtue and vice, had giants for their defense. Addison, born 1672, Pope, born 1688, and their friends and contemporaries, mightily stirred the British mind in the early part of the last century. At the same time, Voltaire, born 1694, Rousseau and Diderot, both born 1712, and their allies, were preparing to shake continental Europe. On the other hand, Turgot in France, born 1727, and Necker in Switzerland, born 1732, gave to the world new and wondrous views and thoughts on finance and the best modes of making a nation great. Still later Mirabeau, born 1749, and Napoleon Bonaparte, born 1769, were rising up to move the world, one with his eloquence, the other with his military genius. If we return to England, we see Johnson, born 1709, early giving token that a man of prodigious powers had come into the world. Lord Chatham, born 1708, Edmund Burke, born 1718, Charles James Fox, born 1749, William Pitt, born 1759, and several of their contemporaries would have made any age or country great. Nor was distinction confined to the Old World. The British colonies shared largely in like honors. In 1706 was born Benjamin Franklin; in 1732, George Washington; in 1735, John Adams; in 1743, Thomas Jefferson; in 1750, James Madison; in 1755, John Marshall; in 1757, Alexander Hamilton; and in 1758, James Monroe—all of them illustrious and some of them peerless.

The same century and people were remarkable for many fine specimens of eloquence. George Whitefield, born in 1714, Samuel Davies, born 1724, James Waddel, born in Ireland, 1739, Patrick Henry, born 1736, and Lord Erskine, born 1750, wielded power that would have been felt in any age. These estimates are not extravagant. When Patrick Henry heard Waddel preach on the creation he said, “When I was listening to that man, it seemed to me that he could have made a world.” Of Henry’s eloquence, Jefferson said it was “bold, grand and overwhelming…. He gave examples of eloquence such as had probably never been excelled.” Of Franklin, Turgot said, Eripuit cœlo fulmen, sceptrumque tyrannis [He snatched lightning from the sky and the scepter from tyrants]. Lord Chatham spoke of Franklin as one whom all Europe held in high estimation for his knowledge and wisdom and ranked him with our Boyles and Newtons—which was an honor not only to the English nation, but to human nature.

And what shall be said of Washington? The strength of his character is found in its symmetry, propriety and high moral principles. He felt exquisitely, but his passions never dictated a single measure of his life. Jefferson’s testimony is clear and has been accepted by mankind. Of Washington he says, “His integrity was the purest, his justice the most inflexible I have ever known, no motives of interest or consanguinity, of friendship or hatred, being able to bias his decision.” Lord Brougham says, “It will be the duty of the historian and the sage, in all ages, to omit no occasion of commemorating this illustrious man, and until time shall be no more a test of the progress which our race has made in wisdom and virtue will be derived from the veneration paid to the immortal name of Washington.”

In such times, and with such contemporaries there was born in Haddingtonshire, Scotland, February 5, 1722, John Witherspoon, the son of a pious, faithful, scholarly minister of the gospel, and a lineal descendant of John Knox of blessed memory.

At an early age he was sent to school at Haddington. Here his good habits, quick conception and rapid progress gave assurance that one day he should fill a large space in the eye of mankind. From fourteen to twenty-one years of age he attended the University of Edinburgh. In each class he was respectable; in the divinity class he displayed much soundness of criticism and remarkable precision of thought.

Leaving the university, he was invited to be the assistant and successor of his honored father, but he preferred to go to the West of Scotland and was pleasantly settled in the parish of Beith. Before long he was called to the town of Paisley. Here both his usefulness and reputation rapidly increased. His fame went abroad, and he was soon invited to Rotterdam in the Low Countries, to Dublin in Ireland, and to Dundee in Scotland. All these proposals he declined. He was shortly there after chosen President of the College of New Jersey in Princeton. At first, he declined but on a renewal of the invitation he accepted and reached America in August 1768 at the age of forty seven. His predecessors in office were eminent ministers of the gospel—Jonathan Dickinson, Aaron Burr, Jonathan Edwards, Samuel Davies and Samuel Findley, all names that cannot be mentioned without profound respect.

In the old country, Dr. Witherspoon had established a high reputation. This followed him to America and gave him great advantage in his labors for the college, in promotion of whose interests he went South as far as Virginia and North as far as Massachusetts. His scholarship was sound and varied. His administrative talents were uncommon. His whole bearing was well suited to inspire confidence and esteem from all classes.

But the troublesome times of the American Revolution were approaching. Conflict with the mother-country was imminent. Soon the world beheld an amazing spectacle—thirteen colonies with a thousand miles of unprotected coast containing less than three million souls were arrayed in war against the tremendous power of the British empire. For a time, the college was closed and in 1776, Dr. Witherspoon, at the age of fifty-four, took his seat in the Continental Congress and with his compatriots signed the Declaration of Independence. For seven years he held this position. His exact knowledge of parliamentary usages, his native wit, his ready apprehension, his moral heroism, profound acquaintance with human nature, and knowledge of constitutional law commanded universal respect. His courage was indomitable. No sad reverses or disasters, no timidity or faithlessness in others, could dampen his ardor or blanch his purpose. As an adviser he had few equals. Regarding public affairs, the passage of time has shown his counsels to be excellent. On questions of the commissariat, finance and public credit, on the proper conduct of the war and like matters, his judgment was outspoken, unfaltering and very safe.

When the Constitution of the United States was framed, Dr. Witherspoon’s wisdom bore an honorable part. But at no time did he abandon the character or duties of a minister of God’s word, preaching whenever he had opportunity.

The war being closed and the form of government settled, Dr. Witherspoon bent his energies to the reviving of the college—no easy task in those days of want and poverty. The heraldry of colleges is registered and read only in their alumni. A few of these—Madison among the number—were coming prominently into notice. But one swallow does not make a summer, and a few students cannot give a college renown. Dr. Witherspoon was also a laborious preacher of the gospel. For these things he laid aside almost all other pursuits.

Having reached the age of seventy, he found his bodily infirmities much increased. More than two years before his death he was blind and suffered other difficulties. But his patience, fortitude and cheerfulness never forsook him. Pain and weakness could not extinguish his ardor. He worked on to the very last. It was a distressing sight when this venerable man was led into the pulpit, and there lifted to heaven his sightless eyeballs in fervent addresses to the throne of grace in behalf of sinful men, and poured out his heart in solemn appeals to his dying fellow-men in behalf of the claims of God. Through life he preached from memory. One or two readings of his written discourses, even by another person, put him in full possession of the contents of his manuscript. He enjoyed the full exercise of his mental powers to the day of his death. He departed this life November 15, 1794, in the seventy-third year of his age.

The writings of Dr. Witherspoon are quite various, both in subject and in style.

(1) His theological writings in his collected works consist of sermons, essays and lectures. There are forty-seven sermons in which are discussed nearly all the leading or vital truths of Christianity, with many kindred matters. Then, we have his essay on justification, covering forty-eight pages, and his practical treatise on regeneration, covering one hundred and sixty-three pages. Then we have his seventeen lectures on divinity. These are quite short, averaging less than seven pages each. Then we have his inquiry into the Scriptural meaning of charity. Of all these writings no one piece is so full and complete as that on regeneration. That on justification is next in order. But if one will allow for their length, several of the sermons are as worthy of attention as any of his works. All his theological writings are remarkable for perspicuity, soundness, earnestness, a just moderation and practicality. It is risking nothing to say that they have had a very powerful influence in molding and establishing the views of large numbers of theologians in all countries where the English language is spoken. This remark is especially true of Ireland, Scotland and North America. It would be a great contribution to our popular theological literature if this land could be well supplied with Witherspoon on regeneration. Will not someone furnish means to do it?

(2) Dr. Witherspoon’s writings on moral matters must not be passed without notice. Of these the most prominent and important are a serious inquiry into the nature and effects of the stage, lectures on moral philosophy and letters on marriage. In all these are found much thought, an excellent judgment and sound speech that cannot be condemned. The piece on the stage was occasioned by the production of the play called Douglas, written by a minister of the Church of Scotland. Dr. Witherspoon’s views on this subject are both calm and spirited. The essay is easily understood; it shows sufficient learning; it is fair and cogent. The lectures on moral philosophy are the most unfinished of all Dr. Witherspoon’s works. He wholly refused to publish them himself, but after his death his students called loudly for them. In them are many good things, but their appearance has not increased their author’s reputation. It is very doubtful, as a question of morality, whether it is ever right to give to the world writings whose author was known to be averse to their publication. And every production is the worse for not receiving the final revision of the author for the press.

(3) Then we have Dr. Witherspoon’s views on many matters respecting public affairs and the political questions of his times. These are all worthy of perusal. Those who control the financial affairs of this country might be both startled and profited by a careful examination of Dr. Witherspoon’s essay on money. He was an independent thinker and freely gave his views on most of the questions which arrested the attention of Americans during their great struggle for independence. Some of his essays for the periodical press, no less than some of his speeches in Congress, are well adapted to make the thoughtful think.

(4) Then we have Dr. Witherspoon’s humorous productions. Some of these are still read avidly. They are so clever and spirited that one can hardly find anything better suited to sharpen one’s wits. The most keen, pungent and highly finished of these productions bears the title of Ecclesiastical Characteristics. The irony is very cutting, the sarcasm is very biting, and the ridicule is overwhelming. In the eighteenth century very few things so stirred Scotland as these caustic productions. The celebrated Bishop Warburton mentioned them “with particular approbation and expressed his wish that the Church of England had such a corrector.” The history of a corporation of servants has in it a rich vein of pure wit hardly less amusing and perhaps more instructive than Gulliver’s Travels by Swift. And Witherspoon’s The Recantation and Apology of Benjamin Towne is another production of the same class.

Dr. Witherspoon’s wit was very uncommon. He was always ready. Whilst crossing the ocean the ship in which he sailed was overtaken by a violent storm. Officers, crew and passengers supposed their end had come. An old sailor, whom Dr. Witherspoon had often and severely reproved for his shocking profanity, came to the man of God during the storm and began to talk piously. At length he said, “If we never see land, I hope we are all going to the same place.” Instantly, Dr. Witherspoon replied, “I hope we are not!” [It is hard to believe Dr. Witherspoon would make such a statement about the eternal destiny of the sailor, and it is perplexing that Dr. Plumer would see this as humorous. Maybe it was the context of its use in the era.]

On occasion of meeting a celebrated wit, Dr. Witherspoon accidentally struck his head against a tall mantel-piece, and he said, “My head rings.” “It rings, does it?” said the witty man. “Yes,” said Witherspoon. “That is because it is empty,” said the wit. Dr. Witherspoon said, “Does not yours ring too when it is struck?” The answer was, “No.” “That,” said Witherspoon, “is because it is cracked.”

In a footnote to his essay on justification, Dr. Witherspoon in a few words fully disposed of Hume’s theory of virtue. True, that subtle and elegant writer had laid himself very liable to contempt by putting wit, genius, health, cleanliness, taper legs and broad shoulders among the virtues. Such men deserve the scorn of serious and good thinkers.

Dr. Witherspoon must have had great power as a teacher over his pupils. His influence, if felt on just a single occasion, was felt for life. Perhaps this continent has produced no man more able in debate than the late William B. Giles, once governor of Virginia. He graduated from Princeton in the class of 1781. Forty-six years after this he thus spoke in the legislature of Virginia.

It happened to be my fortune in early life to be placed under the care of the late celebrated Dr. Witherspoon, of Princeton College. The doctor, although highly learned, was as much celebrated for the simplicity and elegance of his style and for the brevity of his orations as for the extent and solidity of his erudition. He lectured the class of which I was a member upon eloquence and criticism, and I was always delighted with the exercises in that branch of science. Amidst all the refinement of the doctor’s learning he retained much of the provincial brogue of his native town. He generally approached his class with great familiarity with, “How do ye do, lads?” To which the reply was, “braly, Sir, braly.” He commenced his lecture in the simple style of conversation. “Lads, if it should fall to the lot of any of ye, as it may do, to appear upon the theatre of public life, let me impress upon your minds two rules of oratory that are never to be departed from upon any occasion whatever: Ne’er do ye speak unless ye ha’ something to say; and when ye are done, be sure to leave off.

If any pronounce these rules to be insufferably irksome, let him find better. The want of adherence to them is the secret of many failures in our day.

Most of Dr. Witherspoon’s writings fall under some one of the foregoing classes, but some of them are so peculiar as not to be easily classified. On these, time forbids us to dwell.

One thing remarkable in most of his writings is their freshness. They never grow stale. One might instance those fine discourses on “The trial of religious truth by its moral influence,” or “The charge of sedition and faction against good men, specially faithful ministers, considered and accounted for,” or on “The nature and extent of visible religion.”

Of course, the services of Dr. Witherspoon were great. As an educator, as a patriot, as a writer, as a safe and profound thinker on topics of public interest, and above all, as a theologian and preacher, he did great things for the age and the world in which he lived. Perhaps his influence was never greater than at present. Through him many are what they are without knowing that by his means they have been brought to their present line of thought and action. He molded the minds of those who swayed thousands. It seems highly probable that soon a new and complete edition of his works will be called for and will be read with profit and avidity. A man of any force of mind, if familiar with Dr. Witherspoon’s writings, could easily consign to merited disgrace not a few of the foolish notions now more or less popular with the masses and with the demagogues of the country.

Those who revere his memory, therefore, do well and wisely in erecting a public monument which shall tell to the coming generations that if they lack a model to conform them to virtue and renown, they may study the life, examine the writings, and copy the example of John Witherspoon.

In view of the past, the present and the future, we Americans are bound to think of all the ways the Lord our God has led us as a people and learn to trust the Most High in the darkest hour.

Savage and barbarous people often speak of their ancestors, but civilized nations are mightily swayed by the memory of their forefathers. When their deeds have been heroic and virtuous, a just regard to them greatly conduces to the public good. When men are both great and good, their power ought to be immense. Men seldom have wise regard among their posterity unless they can look back with admiration on at least some of those from whom they claim descent. In the example of many of the contemporaries of Dr. Witherspoon we see much that was wise, patient and valiant. Let us honor by imitating their virtues. They have left us a rich inheritance. They braved great perils, they bore great hardships, they practiced simple industry, they subdued the soil to the ploughshare, and they reared a lasting monument to their good name in the institutions they left us. Let us, like them, be just to all men and fear none but the Father of nations and of men.

Our ancestors were an ingenious people. From their day to the present we have had a race of remarkable inventors. Let us encourage all useful arts and contrivances.

Our fathers placed high esteem on mental culture. In the seventeenth century they founded Harvard College in Massachusetts and William and Mary College in Virginia. In the eighteenth century they established about fifty colleges and universities. In the nineteenth century, we have colleges by the hundreds and most of them well deserve the name. Let us largely endow and sacredly guard these noble seats of learning.

The growth of our country has been marked. In 1790 the whole population of the United States was but 3,927,214 souls. Now some of our single States have more. If such things engender pride, they will work our ruin, but if they make us thoughtful and prudent, they will do us good.

Let us not be vain and frivolous, selfish and profane. How Washington reproved profaneness! How Samuel Adams and Benjamin Franklin pleaded for the worship of God in our national councils! Let us not foolishly despise such examples. Nor let us forget that our principles and conduct will mightily affect those who come after us. The next hundred years will probably confirm and establish, or shake and shatter our best institutions. What we and our immediate descendants do will affect the years to come.

When He who made and governs the world has ends to accomplish, he can be at no loss for fit instruments. Divine prescience always provides them. Our fathers were thus fitted for their work. Let us stand in our lot, girt with truth, having faith in God, intrepidly meeting every call of duty, cultivating a sincere good will to all men at home and abroad, and piously leaving all issues in the hands of Him who is in fact and by right the Judge of all the earth.

Before closing this address permit me to read two short papers. One is from an honored descendant of Dr. Witherspoon.

Camden, SC, June 30, 1876

To Rev. Dr. Plumer,

Rev. and Dear Sir: As the lineal descendant of that great and good man Dr. Witherspoon, I deeply regret that I am unable to attend the unveiling of his statue.

His bust that we have I would gladly have taken to Philadelphia. I shall ever feel that I am an American and deeply grateful to the great Presbyterian family of America for the great blessing vouchsafed to us through the exertions of my great-grandfather and his coadjutors. Oh, that the same spirit that actuated them in the hour of their country’s peril may now unite the great American family this Centennial year, knowing no North, nor South, neither East, nor West, but free and happy America!

Yours, very truly,

John Knox Witherspoon

The other is from a source honored by all good men in our land. It has been my happiness to spend the last few days in the company of my old friend, that great and good man, Professor Joseph Henry, of the Smithsonian Institute. He has obligingly handed me the following estimate of Dr. Witherspoon:

He had a mind of great and general powers, harmoniously developed in various directions, capable of analyzing any subject to which his attention might be directed, and of arriving at a clear conception of the fundamental principles on which it was founded. He possessed great facility in deducing logical inferences from general principles, applicable to the affairs of every-day life.

With clear conceptions of truth, he had the moral courage and literary ability to advocate it from the pulpit and the press in forcible language and with apt illustrations.

As an example of these characteristics, I would refer to his essay on the uses and abuses of paper money, which I do not hesitate to say is one of the best expressions of the fundamental principles of the subject to be found in the English language. It was published at a time of great excitement, when the country was suffering under an unstable currency, and is especially applicable to the condition of our own times.

A century ago, Dr. Witherspoon and our fathers were on the busy stage of life. They are gone now. Where shall we be a hundred years hence? Certainly, we shall all be in eternity, but will it be a blessed eternity? Will the world be the better for our having lived in it?