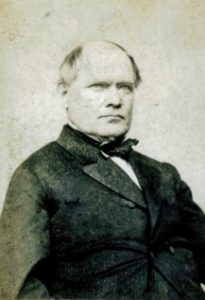

Is it a scowl of anger or grimace of pain that is on the face of Stuart Robinson? His appearance may very well be due to pain. When he was an infant his nurse was tossing him in the air, as adults sometimes do, and watching him giggle, as babies will do, when she accidentally missed him and he fell to the floor. One can only imagine the horror of the nurse as she saw the child she cared for screaming in pain. The injuries were fearful. His right shoulder was dislocated, his hand and thumb were seriously injured, and his head was injured such that the doctor believed, using the terminology of the day, “idiocy,” might be the result. Robinson recovered fully from his head injury but both his arm and hand were disabled for the remainder of his life such that stiffness and awkwardness could be seen in his gestures from the pulpit. Matters were made worse when he broke the same arm in an accident while riding a train from Baltimore to Kentucky. Yes, his facial appearance may very well be due to pain, but then there is the possibility of the scowl of anger, an appearance of antagonism because his character, integrity, and honor as a man and a minister were assailed and slandered such that he sued the source of the defaming words.

Is it a scowl of anger or grimace of pain that is on the face of Stuart Robinson? His appearance may very well be due to pain. When he was an infant his nurse was tossing him in the air, as adults sometimes do, and watching him giggle, as babies will do, when she accidentally missed him and he fell to the floor. One can only imagine the horror of the nurse as she saw the child she cared for screaming in pain. The injuries were fearful. His right shoulder was dislocated, his hand and thumb were seriously injured, and his head was injured such that the doctor believed, using the terminology of the day, “idiocy,” might be the result. Robinson recovered fully from his head injury but both his arm and hand were disabled for the remainder of his life such that stiffness and awkwardness could be seen in his gestures from the pulpit. Matters were made worse when he broke the same arm in an accident while riding a train from Baltimore to Kentucky. Yes, his facial appearance may very well be due to pain, but then there is the possibility of the scowl of anger, an appearance of antagonism because his character, integrity, and honor as a man and a minister were assailed and slandered such that he sued the source of the defaming words.

Stuart Robinson was of Scotch-Irish stock, born November 14, 1814, to James and Martha (Porter) Robinson in Strabane, County Tyrone, Ireland. Martha was the daughter of an elder in the Irish Presbyterian Church and her grandfather had been a Presbyterian minister. Stuart’s father was a successful purveyor of linen until he lost his wealth through guaranteeing some loans that did not work out. Thus, as so many residents of Ireland were doing in the era, James took the family first briefly to New York and then on to Virginia where they settled. When Stuart was but six or seven years old his mother died. The household had no relatives in the United States, so Stuart lived with another family, the Troutmans, through an arrangement by his father.

The Troutmans raised Stuart as their own and came to realize he was highly intelligent. They made sure that he attended the best schools possible. As with several of the biographical subjects presented on Presbyterians of the Past, his intellectual gifts were evidenced by an incredible memory. The Troutmans sought the advice of their pastor, Rev. James M. Brown, regarding the best course for study for Stuart. Brown observed the thirteen year old’s abilities, took him into his home, and directed his studies until he was sent to study in an academy in Romney, Virginia, mastered by Rev. William H. Foote. At about the age of sixteen he professed faith in Christ. When it was time to enter college, Robinson joined the freshman class at Amherst in Massachusetts, graduating in 1836. For preparation for the ministry he studied one year in Union Seminary, Virginia; then he taught for two years to earn tuition for more study; and then studied two years in Princeton Seminary but did not receive a certificate of completion.

Stuart Robinson was licensed by Greenbrier Presbytery, 1841, then ordained, October 8, 1842, at Lewisburg, Virginia (currently in West Virginia) to serve the Kanawha Salines Church. He continued in the ministry serving churches in Kentucky, then Baltimore, and then moved back to Kentucky where he taught in Danville Seminary before becoming minister of Second Church, Louisville. Stuart Robinson was known for his preaching gifts, the precision of his sermons, his pointed and no holds barred writing, and a short-fused temper. His memorialist, J. N. Saunders, commented that, “his temper sometimes got the better of him; that his great will was sometimes too imperious, and that he often said things that were unnecessarily severe and wounding” (p. 34). At the time of the lawsuits that will be discussed in the following paragraphs, Robinson had been at Second Church since 1858.

The story of Dr. Robinson’s litigation begins with The Hickman Courier of Hickman, Kentucky, which reported in March 1872 that an important libel suit had been filed by Rev. Stuart Robinson against the proprietors of the Chicago Evening Post seeking damages of 100,000.00. The compensation sought was described as, likely tongue in cheek, “a moderate sum.” Robinson was responding to a thirty-one word article published that January in the Post’s “Personal and Impersonal” column.

Rev. Stuart Robinson of Louisville, who advocated from the pulpit during the war, the shipping of yellow fever infected clothing to Northern cities, narrowly escaped death from small pox last week.

The purpose of the sentence was likely to inform the Post’s readers of Dr. Robinson’s illness. Despite the availability of an early type of vaccination, the “pox” was a common disease of the day that sometimes horribly scarred the victim. It is believed that the ghostly appearance of Queen Elizabeth, I, of England in her portraits is due to heavy makeup covering her small pox scars. The libelous portion of the piece was the comment that, expressed in a matter of fact manner as though it was common knowledge, Robinson had recommended from the pulpit that the Confederacy engage in what could be called today germ warfare by distributing yellow fever in the North. Could it be the between-the-lines purpose of the snippet was to interpret Robinson’s small pox as a divine judgment for his alleged yellow fever plan? One can only imagine the response of Robinson when he read the slanderous words given the struggles he had controlling his Scots-Irish ire as he grew in grace and sanctification.

The Chicago Evening Post had pursued an investigation into the facts and was “able to speak intelligently in reference to both” the yellow fever plan and Stuart Robinson’s character. The Post determined that one Mr. Conover was the source of the accusation and that it was “utterly without foundation in fact.” Another slice of humble pie was eaten by the Post as it went on to praise the character and integrity of Robinson saying he was “a Presbyterian clergyman of national reputation….For integrity, ability, and all those qualities of head and heart which adorn the profession, he stands second to few clergymen in the country.” Noted further it was said that Stuart Robinson had shown generosity and compassion for the people of Chicago the previous year by giving 1,000.00 to the relief fund for victims of the Great Fire. The Post continued noting that the comment had been added to its “Personal and Impersonal” column from another paper, the name of which is not mentioned. No Post editor had reviewed the piece before its publication. The Post’s confession ends with sorrow, penitence, and a touch of justification for its mistake.

It is the duty of a newspaper to expose and denounce wrong in whatever station or profession it may be found, but no editor can supervise all the items which will creep into his columns. Injustice is thus sometimes done, but the Chicago Evening Post has made it an invariable rule, voluntarily and without condition, as far as possible, to repair the wrong.

In this case, we are sincerely sorry for the publication of this item. We take pleasure in retracting it, and, that no injustice may be done to the party, we hope other papers which copied the items will give the retraction a circulation as extensive as the charge.

What a nightmare for Dr. Robinson. In the nineteenth-century a newspaper often copied the reports of other papers and used them for their own articles. Sometimes the source was cited, but in many cases the source was not mentioned. It was not seen as plagiarism but rather an informal wire service among publishers. If a New York newspaper copied an article from an Atlanta newspaper reporting a fire in a local theater that killed twenty people, then it was the accepted practice to reprint it as its own and no one thought anything about it. When an article was borrowed from another newspaper it was hoped the source from which the account was copied had provided accurate information, but obviously, this was not always the case. Thus, not only did the Chicago Evening Post publish a lie about Robinson, but each newspaper that used the article would have spread the errant information.

As commented above, the Chicago Evening Post did not name the newspaper from which it had obtained the Robinson article, but it could be that the unnamed paper was published in St. Louis. The Hartford Herald of Kentucky, five years after the defamatory piece was published in the Post, reported that a judgment for slander had been made against “the old St. Louis Democrat.” The amount awarded Robinson was 30,000.00, which circa 2014 would amount to over a half million dollars according to computation using the history of the index of inflation. This substantial judgment against the Democrat was just one of a number of suits, including the Chicago one, that was filed by Robinson and in each suit he was “vindicated by the courts.” If the judgments for Robinson were all at the level of the Democrat award, then the already wealthy Robinson would have benefited considerably.

What is to be learned from the disconcerting experience of Stuart Robinson? Obviously, one living in his day would have recognized that defaming Dr. Robinson could be a financially costly mistake. The Epistle of James reminds Christians that the tongue is a fire that can burn out of control (3:6), it is like the tiller of a ship in that its movement directs the whole person (3:4). A more modern but uninspired analogy is that words are like bullets fired from a gun in that once they go forth they cannot be taken back, but even though words cannot maim and kill like bullets they can certainly anger, dishearten, or crush the one at the receiving end. It is doubtful that the one who began the lie, Mr. Conover, would have been concerned about his tongue because at the time the Chicago Evening Post investigated his accusation against Stuart Robinson, he was reported to be in prison for perjury. The reason for his perjury conviction is not given.

Stuart Robinson continued his ministry at Second Church, Louisville, until he was released from the call in June due to declining health. He died from stomach cancer, October 5, 1881. Dr. B. M. Palmer led his funeral service two days later. Dr. Robinson had served as moderator of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS) in 1877, and spoke in the sessions of the Pan Presbyterian Council in Edinburgh, Scotland. He was survived by his wife, Mary Eliza, daughter of William Brigham, M.D., and their two daughters; two sons had died before Dr. Robinson’s death. He was buried in Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville.

If interested in reading more about Stuart Robinson see, A Kingdom Not of this World: Stuart Robinson’s Struggle to Distinguish the Sacred from the Secular during the Civil War, Mercer, 2002, by Preston D. Graham, Jr., which provides a fine intellectual biography with particular emphasis on the doctrine of the spirituality of the church. Also, Robinson’s book, The Church of God as an Essential Element of the Gospel, 1858, has been reprinted by the Orthodox Presbyterian Church, 2009, with an introduction by A. Craig Troxel and a twenty-five page biography by T. E. Peck. Peck was a friend of Robinson and succeeded him at Central Presbyterian Church, Baltimore. Robinson also published Discourses on Redemption: As Revealed at Sundry Times and in Divers Manners, Richmond: Presbyterian Committee of Publication, 1866.

Barry Waugh

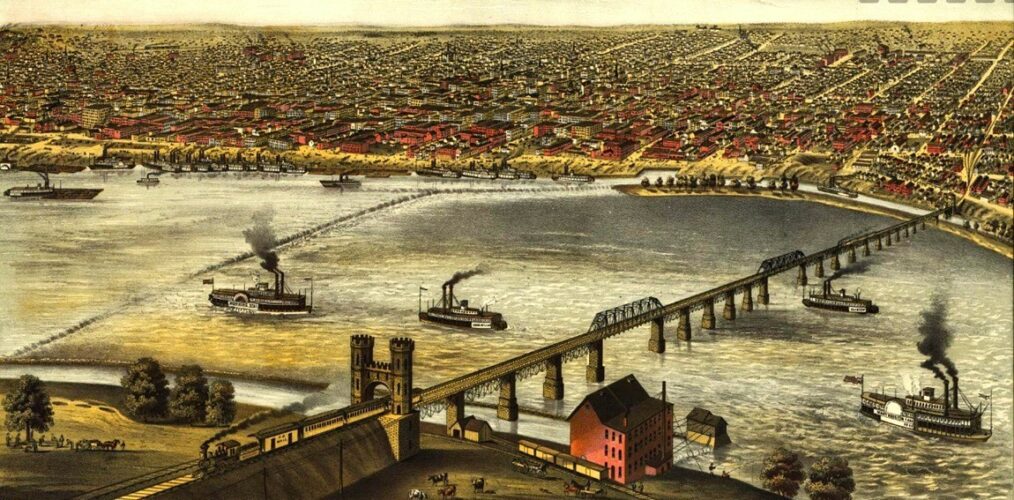

Notes–The header is cropped from a view of Louisville from across the Ohio River in Indiana titled, “Bird’s eye view of Louisville, Kentucky 1876,” as from the Library of Congress digital collection; Second Presbyterian Church is to the upper right with two steeples (see: A Manual for the Members of the Second Presbyterian Church in the City of Louisville, Kentucky, by Eli Newton Sawtell, 1833, for a larger picture of the church). Robinson did not receive his certificate of completion at Princeton, see the seminary biographical catalog of 1909, its index listing for him regarding note “b,” and the preface explanation of “b”. Thank you to Wayne Sparkman of the PCA Historical Center for use of the photograph of Robinson; the other portrait of Robinson as a younger man is from Nevin’s Presbyterian Encyclopedia, but it is not a very good image when compared to the other nice ones in Nevin. The other sources, other than the Princeton Seminary Necrological Report for Robinson, are given in the article. The memorial by J. N. Saunders is Memorial Upon the Life of Rev. Stuart Robinson, D.D., Richmond: Presbyterian Committee of Publication, 1883.