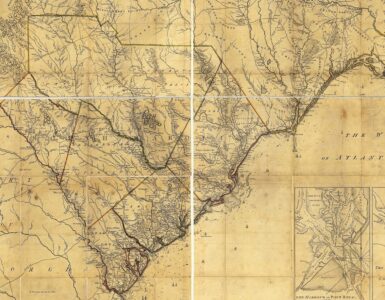

A drive east on Fork Church Road south of Columbia, South Carolina, just a short distance from Gadsden will pass Old Richland Presbyterian Church in lower Richland County. According to Robert Mills in Statistics of South Carolina, “The name of this district is said to have originated from the large bodies of rich highland swamp which border on its rivers.” The narrow road cuts through farmland as the intermittent wind-break rows of trees go by until a white church is seen ahead on the right. When I saw the church in July 2006 its exterior was covered with bright white paint, secured with black double doors and shutters, and the enclosed cemetery was neatly kept. The church is as it has been for over a century with its arched Gothic entry set in an octagonal steeple accessed by simple wooden steps. The application filled out to select Old Richland as a National Historic Landmark notes the interior has plastered walls, board-and-batten ceiling, and wood floors, but the pulpit, pews, and other furnishings are missing. I was on the property for about half-an-hour and not one vehicle passed on the road; there was no noise from anything on a breezy, clear but hot day.

A drive east on Fork Church Road south of Columbia, South Carolina, just a short distance from Gadsden will pass Old Richland Presbyterian Church in lower Richland County. According to Robert Mills in Statistics of South Carolina, “The name of this district is said to have originated from the large bodies of rich highland swamp which border on its rivers.” The narrow road cuts through farmland as the intermittent wind-break rows of trees go by until a white church is seen ahead on the right. When I saw the church in July 2006 its exterior was covered with bright white paint, secured with black double doors and shutters, and the enclosed cemetery was neatly kept. The church is as it has been for over a century with its arched Gothic entry set in an octagonal steeple accessed by simple wooden steps. The application filled out to select Old Richland as a National Historic Landmark notes the interior has plastered walls, board-and-batten ceiling, and wood floors, but the pulpit, pews, and other furnishings are missing. I was on the property for about half-an-hour and not one vehicle passed on the road; there was no noise from anything on a breezy, clear but hot day.

The Richland Church began, as did many churches organized in America in the nineteenth century, with a mission Sunday School. Beginning in 1873 classes likely met in an earlier structure, residence, or outbuilding on or near the Old Richland site. The Sunday School was taught by Thomas Luther Haman, a senior at Columbia Theological Seminary. Providing oversight and assistance was the evangelist for Charleston Presbytery, John Reid Dow. Dow was an immigrant from Scotland that began American life in Georgia operating a store, but was then called to the ministry with his first charge at the John’s Island and Wadmalaw Island Churches. He would go on to be stated clerk of his presbytery for twenty years ending with his death from pneumonia in 1895. Haman’s ministry at Richland was short because he returned to Mississippi for ordination and installation as pastor of First Church, Greenwood. The group interested in having a church continued using the property because the earliest decipherable burial date on a grave marker in the cemetery is 1878.

The Richland Church began, as did many churches organized in America in the nineteenth century, with a mission Sunday School. Beginning in 1873 classes likely met in an earlier structure, residence, or outbuilding on or near the Old Richland site. The Sunday School was taught by Thomas Luther Haman, a senior at Columbia Theological Seminary. Providing oversight and assistance was the evangelist for Charleston Presbytery, John Reid Dow. Dow was an immigrant from Scotland that began American life in Georgia operating a store, but was then called to the ministry with his first charge at the John’s Island and Wadmalaw Island Churches. He would go on to be stated clerk of his presbytery for twenty years ending with his death from pneumonia in 1895. Haman’s ministry at Richland was short because he returned to Mississippi for ordination and installation as pastor of First Church, Greenwood. The group interested in having a church continued using the property because the earliest decipherable burial date on a grave marker in the cemetery is 1878.

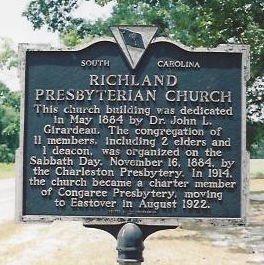

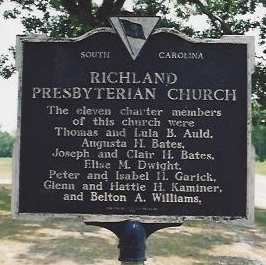

In 1883, a building committee was chosen consisting of J. J. Kaminer, G. A. Kaminer, Joseph Bates, J. P. Garrick, T. H. Auld and S. J. Dwight. The land for the cemetery and church was donated by the Joyner family. Construction began in 1883 with the clapboard building completed the next year. The church was dedicated to the glory of God in May 1884 with a service conducted by native South Carolinian and Professor of Didactic and Polemic Theology at Columbia Seminary, John L. Girardeau. His sermon text was the second half of Isaiah 6:13. It would be interesting to have heard how he interpreted and applied this passage.

As a teil tree, and as an oak, whose substance is in them, when they cast their leaves: so the holy seed shall be the substance thereof.

The Richland flock had a suitable building, but it needed to become an organized congregation of the Presbytery of Charleston in the Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS). In the fall during the meeting of the Synod of South Carolina in First Church, Greenville, Stated Clerk Dow reported for the Presbytery of Charleston that:

A neat and commodious house of worship has been erected and dedicated near Gadsden, in Richland County, and a commission has been appointed to organize a church there at an early day. (Minutes, p. 8)

At the time of organization on the Sabbath, November 16, 1884, the congregation consisted of eleven communing members including two ruling elders and a deacon. As the church continued using supplies for leading worship, included were seminary students developing their gifts for licensure and ordination, as well as ministers, ruling elders, and teachers. Some of those that filled the Old Richmond pulpit then went on to other places and ministries, such as the future president of Chicora College, Samuel C. Byrd; William M. Anderson, Sr., would serve in Texas and Tennessee at First Church in Dallas and Nashville; Dr. Richard Thomas Gillespie, would be chosen a future president of Columbia Seminary; and Hugh R. Murchison would be a chaplain and professor at the University of South Carolina. As the congregation continued ministry at its first site it never had more than 35 communicant members and at one time had three elders and two deacons. The women of the congregation raised funds to purchase an organ, chandeliers, and a silver communion service. As South Carolina’s economy shifted from agriculture to manufacturing and the population relocated due to rapid growth of the textile industry, Old Richland joined other churches transferred mostly from the Presbytery of Charleston to establish a new presbytery named Congaree in 1914 (Presbyteries of Harmony and Bethel also provided churches).

In 1919 it was decided the congregation should move from its idyllic location into a new building in Eastover just a few miles away. The land there was donated by H. G. Bates, L. M. Yelton, F. G. Auld, and C. G. Rowland, and the building committee consisted of R. C. Hamer, J. N. Hardee, F. G. Auld, Alfred Scarborough, and J. B. Bates. The move was started during the pastorate of Arthur P. Toomer (1918-1920), then continued during the supply tenure of Edgar A. Dillard. The congregation settled in its new brick church in August 1922. The new church continued the Richland Presbyterian Church name while the first property came to be called Old Richland. At the time Mrs. Bates wrote her history of Richland for Jones and Mills (see notes), the congregation had over fifty communing members, but at some point during the years that followed it appears Richland at Eastover was closed, possibly after 1984.

Old Richland Church is one of many church buildings throughout the nation that are no longer used for their originally intended purpose. In Richland’s case, an opportunity for growth amidst regional change brought about moving to a new property. Some church buildings have been closed because of schism, population shifts, moving to a larger property, two or more churches became one, or due to shifts in commitment as doctrinal distinctives become for some members divisive rather than what they are—the source for unity in the truth of the Gospel. It has become common for energetic home buyers to purchase fire houses, light houses, grist mills, store fronts, schoolhouses, and other old buildings and make them into homes. What a wonderful idea it is for these structures to be re-made as residences and continue their existences as artifacts of the nation’s architectural and social history. People also buy old churches and make them into residences, but even if I wanted to restore an old building, a church would not be on my list of prospective properties. Old churches had a spiritual purpose as places for the corporate worship of God and they should be treated with dignity because of their unique place in history. We call retired teaching elders (or ministers), ruling elders, and deacons emeritus, so why couldn’t Old Richland be called a Church Emeritus?

Barry Waugh

PS–If you enjoy old churches and their design take a look at the Old Churches and Church Design categories.

Notes—There is a Richland Presbyterian Church north of Richland between Seneca and Westminster. The photographs were taken by the author in 2006. A book I could not access that would likely have corrected my assumptions and filled in gaps particularly with reference to the Eastover years is Francis K. Roberts, editor, 1884-1984: Richland Presbyterian Church, Eastover, South Carolina, Columbia: Eastside Printing Company, 1984; it is a pamphlet of 56 pages. The earliest burial in the Richland cemetery was determined on the basis of those listed on Find-a-Grave. Sources include the Richland Church article by Mrs. Joe Bates on pages 668-70 in Jones and Mills, History of the Presbyterian Church in South Carolina Since 1850, Columbia: The Synod of South Carolina, 1926. Also helpful is, Margaret Adams Gist, editor, Presbyterian Women of South Carolina, [n.p.]: Women’s Auxiliary of the Synod of South Carolina, 1929; this book contains all kinds of information in its 785 pages as well as several portraits of women including Florence Earl Thornwell (Mrs. J. H.), but access to the material is hampered by lack of an index. C. N. Willborn’s “John L. Girardeau: Pastor to Slaves and Theologian of Causes,” Ph.D. dissertation, Philadelphia: Westminster Theological Seminary, 2003, provides the definitive study of Girardeau. The South Carolina Department of Archives and History information page for Richland Church as a National Register Property in South Carolina is titled, “Richland Presbyterian Church, Richland County (S.C. Sec. Rd. 1313, Gadsden vicinity)”; the page includes links to historic documents and applications for the “Lower Richland Multiple Resource Area” that includes seventeen historic buildings. The Robert Mills source is, Statistics of South Carolina (Charleston: Hurlbut and Lloyd, 1826; reprint, Spartanburg: The Reprint Company, 1972), 692-93. Information about John Reid Dow is from his obituary in the Charleston News and Courier, Tuesday, December 24, 1895, p. 3, as found on Dow’s Find-a-Grave entry (portrait there too). For more about Columbia Seminary see, “Review, Our Southern Zion: Old Columbia Seminary, David B. Calhoun.”