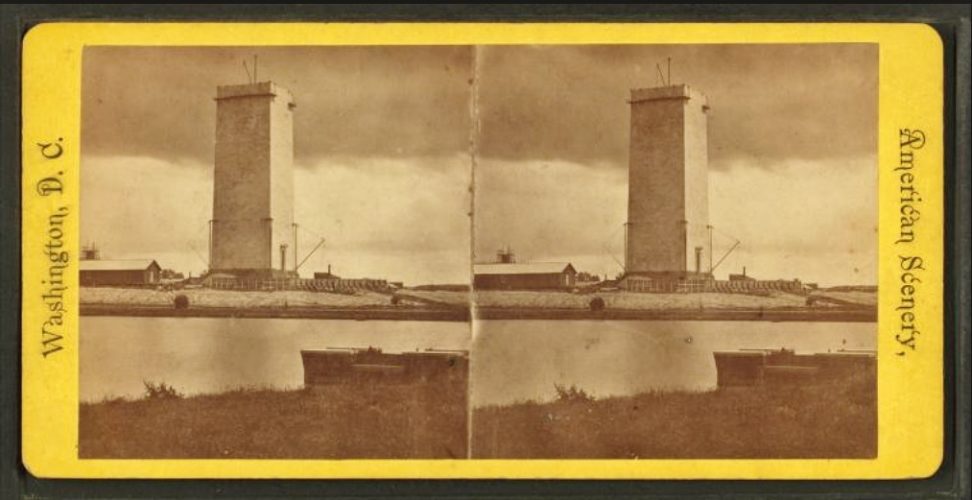

Pictured in the header is the Washington Monument during the process of construction. It currently towers 555 feet and can be seen from just about anywhere in the national capital. Thanks to a building height limitation in Washington, the monument continues to be the capital’s tallest building. It has been noted previously on this site in the biography of E. A. Smyth that the life stories posted are heavily weighted towards members of the clergy—whether they are called teaching elders or ministers. The reason for the imbalance is that ruling elders, deacons, and other church members are known to historians for their professions and public presence but not necessarily for their church work. In the case of the Washington Monument a Presbyterian enters the picture because it was designed by a gifted and talented architect, Ruling Elder Robert Mills. Mills was an industrious, creative, well-known figure in his day, but his importance to architectural and church history has been lost to the passage of time.

Pictured in the header is the Washington Monument during the process of construction. It currently towers 555 feet and can be seen from just about anywhere in the national capital. Thanks to a building height limitation in Washington, the monument continues to be the capital’s tallest building. It has been noted previously on this site in the biography of E. A. Smyth that the life stories posted are heavily weighted towards members of the clergy—whether they are called teaching elders or ministers. The reason for the imbalance is that ruling elders, deacons, and other church members are known to historians for their professions and public presence but not necessarily for their church work. In the case of the Washington Monument a Presbyterian enters the picture because it was designed by a gifted and talented architect, Ruling Elder Robert Mills. Mills was an industrious, creative, well-known figure in his day, but his importance to architectural and church history has been lost to the passage of time.

Robert was born in Charleston, South Carolina, the son of William and Anne (Taylor) Mills. His father emigrated to America from Dundee, Scotland, 1770. Anne and William were sheep of the flock gathered in the cote of First Scots Presbyterian Church. William was a tailor. When his parents passed away in 1790 and 1802, both were buried in the churchyard. Young Robert may have been tutored by his brother before formal preparatory education at the College of Charleston. He had an artistic sense which combined with an engineering penchant meant that building design would be his future. Just as divinity students were taught by ministers and other students read law with attorneys, Mills chose a skilled and respected mentor for instruction in architecture, James Hoban. As has been seen on Presbyterians of the Past, John McArthur, Jr. in a later generation was tutored by another great architect, Thomas U. Walter (1804-1887). Hoban learned construction and drawing as a lad in Dublin and was involved in restoration of the first South Carolina State House, which was in Charleston, but he is more commonly known for designing the White House. He drew up the plans for the presidential residence and saw his vision through to completion in 1800. Hoban was the obvious choice for Mills. As young Robert headed for the national capital and Hoban’s teaching, he passed the recently completed capitol of Virginia in Richmond. It was created by Thomas Jefferson and Charles-Louis Clérisseau and is situated on the highest point of the city. In Mills’s day, before modern structures blocked much of it from view, it could be seen clearly from a distance as a symbol of the pinnacle of government, Jeffersonian Republicanism. Mills was impressed with what he saw. Arriving in Washington, he settled in to absorb the basics of statics, design, and structural engineering from James Hoban.

After studying with Hoban, Mills was invited by President Jefferson in 1803 to live in Monticello for further study. Such an opportunity could not be passed up. Jefferson’s well-known bibliomania included a collection of architecture books that may have been the most comprehensive in North America. Mills must have felt like he was set free to raid the local balustrade and pilaster architectural shop. Greek Revival architecture would influence him as it had Jefferson, and the president’s books provided the text and drawings required for mastering nuances of the movement. Jefferson also played a part in his marriage. Mills and Eliza Barnwell Smith were married in 1806 following a courtship began when he delivered a letter from Jefferson to Eliza’s father Gen. John Smith. Jefferson and Mills maintained their friendship over the years. Mills gave Jefferson a drawing of the Bank of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. As of the posting of this biography, the drawing is displayed in the dining room of Monticello.

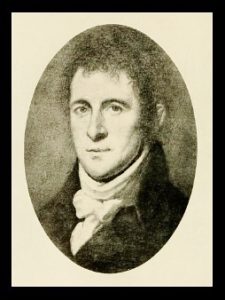

Having begun architectural studies with Hoban, then continuing with volumes from the library of polymath Jefferson, Mills enhanced his curriculum with instruction from Benjamin H. Latrobe (1764-1820). Latrobe studied and worked in Europe before emigrating to the United States in 1795. Latrobe’s Bank of Pennsylvania had entranced Mills and he considered the transplanted Yorkshire Englishman the greatest influence on his work. How would Mills get his foot in the door of the great architect’s office? His friend Jefferson provided the recommendation needed to work with Latrobe.

Having begun architectural studies with Hoban, then continuing with volumes from the library of polymath Jefferson, Mills enhanced his curriculum with instruction from Benjamin H. Latrobe (1764-1820). Latrobe studied and worked in Europe before emigrating to the United States in 1795. Latrobe’s Bank of Pennsylvania had entranced Mills and he considered the transplanted Yorkshire Englishman the greatest influence on his work. How would Mills get his foot in the door of the great architect’s office? His friend Jefferson provided the recommendation needed to work with Latrobe.

During the years in Philadelphia, Mills submitted a plan for building South Carolina College. A prize of three-hundred dollars had been offered for the winning plan by the design committee. Included among the ten individuals submitting drawings, correspondence, or ideas was President Samuel S. Smith of Princeton College in New Jersey. In the end, the committee did not accept any single plan but instead drafted its own drawings using concepts from the designs by Mills and a man with the surname Clark. Even though the committee’s decision appears to be a thinly veiled unwillingness to pay the prize, the members voted to give half of the fee to each man. Maybe Bertram Wyatt-Brown would deem this Southern honor, but then the committee may have had more pragmatic concerns because it wanted to keep Mills interested in the project for drafting some of the drawings used for the first college building, Rutledge Hall. Even at this early stage in Mills career, his gifts were obvious. Rutledge was completed in 1805 and exists today despite fires, war, and storms, but it has been modified. While Mills continued designing in Philadelphia, he drew up the plans for the Congregational Church in Charleston known as the Circular Church, which he layed out with an auditorium floor plan particularly suited for preaching the Word.

As the time passed working with Latrobe, Mills increased popularity and commissions led to establishment of his own practice in Philadelphia where he continued into 1817. In 1812 Mills renovated the municipal office wings of the Old State House (Independence Hall). Among his designs were a row of houses on Ninth Street between Locust and Walnut; Washington Hall, a large auditorium; Octagon Unitarian Church, dedicated February 14, 1813; and Sansom Street Baptist Church. His designs were not limited to buildings but included the protective enclosures for the wooden Upper Ferry Bridge across Neshaminy Creek which is believed to have been the longest spanned wooden bridge in the nation at the time. Mills’s sketch of the Bank of Philadelphia given to Jefferson may have been a way of showing his presidential mentor that he had done well as he transitioned across the Mason-Dixon Line. From Latrobe, the father of the Greek Revival in America, he absorbed not only design, but also his principles of administrative professionalism and the science of building and aesthetics. Mills’s next project would be a turning point in his professional development.

On December 26, 1811 the Richmond Theater Fire occurred in Virginia. In order to remember the catastrophe and avoid desecration of the bodily remains left on the site, Mills was commissioned to design Monumental Church. Monumental is still standing with its octagonal design and columned portico on the site of the fire. It was an important architectural project for Mills because it led to other commissions in Richmond. One set of plans was drawn up for the Wickham House, a residence completed in 1812. That same year First Presbyterian Church in Augusta, Georgia, was designed by Mills and dedicated May 17. The church stands today but it was refaced in 1847 and one of its pastors, Joseph R. Wilson, was the father of President Woodrow Wilson. Other work in Richmond included submission of a design for the Court House in 1814 (apparently not used). The Dr. John Brockenbrough house was completed in 1818 and was later occupied by Jefferson Davis during his presidency and is currently the White House of the Confederacy Museum. Presbyterian Robert Mills began his work in Quaker Philadelphia but found expanded opportunities in the former Church of England stronghold of Richmond.

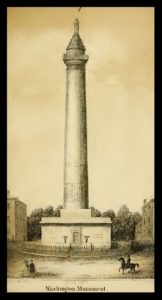

As has been mentioned, Mills is known for designing the Washington Monument in the nation’s capital, but the great obelisk was not his first tribute to the country’s founding father. The city of Baltimore commissioned him to design a memorial as the winner of the competition for a plan. His proposed single column monument might be considered a form study for his more famous towering tribute to General Washington in later years. The corner stone was laid in Mount Vernon Place on July 4, 1815, and fourteen years later on November 25, 1829, Robert Mills issued an announcement inviting people to the setting of Italian sculptor Henrico Caucici’s statue of George Washington atop the grand pillar.

As has been mentioned, Mills is known for designing the Washington Monument in the nation’s capital, but the great obelisk was not his first tribute to the country’s founding father. The city of Baltimore commissioned him to design a memorial as the winner of the competition for a plan. His proposed single column monument might be considered a form study for his more famous towering tribute to General Washington in later years. The corner stone was laid in Mount Vernon Place on July 4, 1815, and fourteen years later on November 25, 1829, Robert Mills issued an announcement inviting people to the setting of Italian sculptor Henrico Caucici’s statue of George Washington atop the grand pillar.

ELEVATION OF THE STATUE.

The public are respectfully invited to witness the final elevation of the Statue of Washington to the summit of the Monument this day at 12 o’clock, should the weather prove favorable, if not, on the first fair day after.

Seats are provided for the public authorities, adjoining those of the Managers of the Monument, fronting the works Seats [contractors?], are also provided for those venerable and honorable survivors of the Revolutionary war who may attend—and such are earnestly invited to witness this public expression of their country’s gratitude, not only to him who led her armies to victory, and established her liberties upon a sure basis, but through him to all those noble spirits who fought and bled under his banner.

ROBT. MILLS, Architect, November 25, 1829

As was his experience with Monumental Church in Richmond, his Washington project led to additional commissions in Baltimore, such as First Baptist Church (“Old Round Top”) and St. John’s Episcopal Church. Mills expanded his design interests by turning more to public works projects and increasing his civil engineering efforts. He was supervisor of the city’s water works, which likely provided the experience needed for his return to South Carolina for a new job.

In 1820 Mills relocated his family to Charleston so he could work for the state board of public works. Residence in his hometown proved impractical because the hub of state government was in Columbia, so the family moved once again. In his new position Mills directed an extensive program of improvements on roads, rivers, and canals. His book A Treatise on Inland Navigation: Accompanied by a Map was published in 1820 and it showed readers his knowledge of the subject. Extensive waterway ventures were accomplished under his direction on the Saluda, Broad, and Catawba rivers including canals with locks connecting the waterways and bays into a navigable highway system. By 1826 he boasted in Statistics of South Carolina, Natural, Civil, Military, History, General that the state had 2,370 miles of inland navigation. Not only did he improve transportation by water, but there are many structures and other evidence of Mills throughout the state. Lancaster County’s jail was completed in 1823 according to plans by Mills; the South Carolina State Hospital (originally, South Carolina Lunatic Asylum) in Columbia opened its doors in 1822; and in Charleston is his “Fireproof Building” which is the oldest such building in the nation. Additional jails were drawn up by Mills in Union, Spartanburg, and Yorkville (York), but work for the criminal justice system did not end with incarceration because he provided plans for administering judicial decisions in courthouses in Greenville County in Greenville, Newberry County (possibly), Fairfield County in Winnsboro, and Kershaw County in Camden. The Mills design portfolio includes numerous entries in South Carolina.

When the Mills family moved from Charleston to Columbia, they became members of First Presbyterian Church in the fall of 1821 during the pastorate of Thomas C. Henry. The information about their time in the church is limited but their memberships continued through the pastoral call of Robert Means. During Means ministry in May 1824, Mills was elected a ruling elder along with James Young and a physician named Thomas Wells. The three were ordained and attended their first session meeting June 12, 1824. Mills was one of the signers of the deed to the church property. Attendance of session meetings by Elder Mills was consistent until 1826 when he was absent and church attendance became irregular likely due to travel for work. As far as sessional records go, his name does not appear after 1828. While in Columbia the family lived at the intersection of Pendleton and Sumter Streets by the South Carolina College campus. Continuing financial troubles led to the property being foreclosed in 1825. Robert and Eliza’s son, John Smith Mills, was born September 13, 1820, but he died just two years later July 13, 1822. The toddler is buried in the southwest corner of the churchyard plot west of the George Howe family. Mills was working in Camden on construction of the Bethesda Presbyterian Church at the time of John’s death. A consequence of his residence in Columbia was designing a home for fellow church member, Ainsley Hall. Mills may have taken the commission because he owed Hall money, so designing and overseeing construction was a way to cover a debt. The Mills family, despite Robert’s success, struggled financially all his life. Ainsley Hall died and never resided in his grand mansion. The stately home and its four acres became the campus of Columbia Theological Seminary before serving Columbia Bible College. The house is extant as the Robert Mills House and can be visited.

With the cessation of state appropriations for public works in 1830, Mills moved to Washington where he would continue to live until his death. He was appointed Architect of Public Buildings in the nation’s capital which was a position he held for fifteen years. Included in his portfolio were three key federal buildings—the Treasury was completed 1839, the Patent Office opened in 1840, and the Post Office. He designed some Marine Hospitals, the jail in Washington (1839), the courthouse in Alexandria (1838), and continued working in his home state by designing the Library at South Carolina College (1838, currently South Caroliniana Library). Four customs houses for the government were built from his plans—two in Connecticut and two in Massachusetts including the elaborate one in New Bedford. During his years in Washington, Mills published books related to his public works service such as The American Pharos, or Lighthouse Guide (1832), and a Guide to the Capitol of the United States, which first appeared in 1834 and continued to be printed in several editions. His work increasingly enjoyed attention and his duties for the U. S. Government and other entities established him as the premier architect in the nation.

The pinnacle of the South Carolinian’s legacy is the Washington Monument in the District of Columbia. The corner stone was laid in 1848. After a good beginning, the project languished for lack of funds, politics, dampened enthusiasm, and squabbling resulting in suspension of construction when the structure had only reached a height of 152 feet in 1855, the year Mills died. In spite of the efforts of the Monument Association it could not be resumed, and it was not until after years of controversy that Congress, in 1878, facilitated restarting the project. Thirty-six years after it was started, Mills’s magnum opus was completed in 1884. At the time, the Washington Monument was the tallest structure in the land. Mills’s experience with his obelisk was similar to that of John McArthur, Jr. with Philadelphia’s city hall. The Washington Monument is grouped with other capital buildings in the heart of the city such as the White House and presidential memorials, but certainly none of the buildings can be seen from as far away as the Washington Monument.

The pinnacle of the South Carolinian’s legacy is the Washington Monument in the District of Columbia. The corner stone was laid in 1848. After a good beginning, the project languished for lack of funds, politics, dampened enthusiasm, and squabbling resulting in suspension of construction when the structure had only reached a height of 152 feet in 1855, the year Mills died. In spite of the efforts of the Monument Association it could not be resumed, and it was not until after years of controversy that Congress, in 1878, facilitated restarting the project. Thirty-six years after it was started, Mills’s magnum opus was completed in 1884. At the time, the Washington Monument was the tallest structure in the land. Mills’s experience with his obelisk was similar to that of John McArthur, Jr. with Philadelphia’s city hall. The Washington Monument is grouped with other capital buildings in the heart of the city such as the White House and presidential memorials, but certainly none of the buildings can be seen from as far away as the Washington Monument.

Robert Mills continued to work extensively in Washington and other locations for the remainder of his life. He died about half-past seven Saturday morning, March 3, 1855. Eliza and Robert had been blessed with four girls in addition to John Smith—Eliza Virginia, Jacqueline Smith, Mary Powell, and Sarah Jane. Despite prominence in his field, he died as he had lived, a man of modest means. Liscombe (Altogether American) notes his estate was valued at 390.50, which was not impoverished but one might expect a professional man to have accrued more. Eliza struggled to cover the debts which Liscombe concludes exceeded a thousand dollars, but fortunately, due to the sale of some property, the debts were covered. Eliza managed to live her last ten years in their home in Washington at 553 New Jersey Avenue at the corner of B Street South. Money was not only a personal issue for the Mills family, it was also a public one because Mills’s designs often suffered budget overages leading to public and government outrage. It is difficult to tell whether the intention of the article, “Cost of Public Buildings,” in The Jeffersonian, March 8, 1855—note just after Mills died—was to honor Mills or dishonor his memory because the prices of several public buildings are given. However, the piece ends stating the “Treasury, Patent Office, and General Post Office were all erected by Robert Mills and they are constructed in the most substantial manner.” Whether cost efficient or not, the buildings were made to last. The Baltimore American, as reprinted in the Alexandria Gazette, March 7, mentioned his monument to Washington at Mount Vernon Place, twelve buildings on Calvert Street known as Waterloo Row, and his efforts to direct the water from Jones Falls around the city of Baltimore. Robert Mills is buried in Congressional Cemetery in Washington, plot number 111. He did not have a monument on his grave until 1930 (or 1937) when concerned, admiring, and indebted architects funded one.

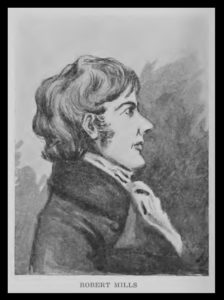

According to a Washington lady who knew Mills in her youth, he was “a man of strikingly strong features, of evidently studious habits, with an air of deep absorption or abstraction; a man of unusual dignity and reserve, yet affable and kindly. He was of simple and correct taste in dress, and his presence was always an interesting one to everybody.” She also spoke of his regular attendance at the Presbyterian Church and of his one vice, the intemperate use of snuff.

Barry Waugh

Notes–I am indebted to Ruling Elder and Calvary Presbytery Stated Clerk Mel Duncan for introducing me to Robert Mills during a tour of Greenville, South Carolina several years ago. Here is the link to Robert Mills’s “Plans for Augusta Church the State of Georgia.” The header image, the incomplete Washington Monument in DC, and the color picture postcard are from the New York Public Library Public Domain collection. The portrait of Mills is from Early Philadelphia Architects and Engineers, by J. Jackson, and the second portrait is Benjamin Latrobe as in his book, The Journal of Latrobe, 1796 to 1820. My Mills biography began with assistance from Fiske Kimball’s entry in vol. 13 of Dictionary of American Biography, Mills-Oglesby, edited by Dumas Malone. Some information regarding his work in Philadelphia was located in Philadelphia: A 300 Year History, New York: Norton, 1982. Altogether American: Robert Mills, Architect and Engineer, 1781-1855, by R. W. Liscombe, Oxford, 1994, is a fine study which includes illustrations. The Philadelphia row houses were studied in “Robert Mills and the Philadelphia Row House,” by Kenneth Ames in Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 27:2 (May 1968), pages 140-46. The South Carolina State Government was located first in Charleston, but it was then moved to Columbia, the geographic center of the state, when the South Carolina Assembly voted to do so in 1786; republicanism required not only equitable representation but also fairness of travel distance for legislators. Pictures of Mills’s South Carolina College design submission are available on page 14 of John Morrill Bryan’s book, An Architectural History of the South Carolina College, 1801-1855, they are also provided in color following the title page. The biography of Mills by Rhodri Windsor Liscombe in Walter Edgar’s edited The South Carolina Encyclopedia was used and it includes a select bibliography. See the text of an interview on NPR titled “How D.C.’s Height Limit Has Shaped the Capital,” which addresses a recent attempt to raise the limit from the standard enacted in 1910. Mills’s marriage and the Thomas Jefferson connection is from a letter on National Archives: Founders Online, “Robert Mills to Thomas Jefferson, 4 June 1810.” Information about Mills in Columbia and First Church is from Blanche Marsh, Robert Mills: Architect in South Carolina, Columbia: R. L. Bryan Company, 1970. Howe’s history of Presbyterians in South Carolina, and David B. Calhoun’s The Glory of the Lord Risen Upon It: First Presbyterian Church Columbia, South Carolina, 1795-1995, briefly note Mills at First Church. The nicely done video, “First Presbyterian Church, Columbia, South Carolina, Churchyard Tour with Tom Gottshall,” was helpful regarding Mills’s work in First Church. The newspapers The Jeffersonian and Alexandria Gazette were accessed on the Library of Congress, Chronicling America site. Some materials by Mills and early publications about him are available online, such as, Design No. 1 for a Marine Hospital on the Western Waters to Accommodate 100 Patients, 1837, which includes drawings of the project, and Design No. 2 for a Marine Hospital on the Western Waters to Accommodate 50 Patients; if the two are taken together it appears Mills offered the government greater and lesser cost options by patient-count restraints. There may have been no one who knew Washington, DC as well as Mills, so it is not surprising that he published Guide to the Capitol and to the National Executive Offices of the United States, 1851, which was preceded by Guide to the National Executive Offices and the Capitol of the United States, 1841. A very important contribution by Mills for historians is Atlas of the State of South Carolina: Made under the Authority of the Legislature: Prefaced with a Geographical, Statistical and Historical Map of the State, 1825.