Reformed theology in the American Colonies developed primarily among those who spoke English from Scotland, Wales, Ireland, and England. Reformed societies from the western Continent such as the Swiss, German, Dutch, and French tended to establish their own communities where communication was achieved using their native languages. The Huguenot churches in America were dissolved over the years as the French Reformed joined Presbyterian or other Reformed denominations, but speakers of German and Dutch tended to worship exclusively in their own languages into the nineteenth century with some congregations coming to have both Dutch and English services. Danny E. Olinger provides the historical context for Geerhardus Vos: Reformed Biblical Theologian, Confessional Presbyterian, Reformed Forum, 2018, observing that knowledge of Reformed Dutch theology in America was impeded by the hesitancy of the Dutch to transition to using English. However, in recent years Dutch titles from the past have been translated with the prospects for future translations promising. Geerhardus Vos may be known for his exegetical and biblical theological work, but in conjunction with his scholarship is his significance as the first native speaker of Dutch on the faculty of Princeton Seminary which gave him the opportunity to produce works in English.

Reformed theology in the American Colonies developed primarily among those who spoke English from Scotland, Wales, Ireland, and England. Reformed societies from the western Continent such as the Swiss, German, Dutch, and French tended to establish their own communities where communication was achieved using their native languages. The Huguenot churches in America were dissolved over the years as the French Reformed joined Presbyterian or other Reformed denominations, but speakers of German and Dutch tended to worship exclusively in their own languages into the nineteenth century with some congregations coming to have both Dutch and English services. Danny E. Olinger provides the historical context for Geerhardus Vos: Reformed Biblical Theologian, Confessional Presbyterian, Reformed Forum, 2018, observing that knowledge of Reformed Dutch theology in America was impeded by the hesitancy of the Dutch to transition to using English. However, in recent years Dutch titles from the past have been translated with the prospects for future translations promising. Geerhardus Vos may be known for his exegetical and biblical theological work, but in conjunction with his scholarship is his significance as the first native speaker of Dutch on the faculty of Princeton Seminary which gave him the opportunity to produce works in English.

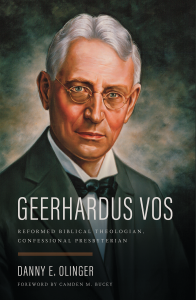

Geerhardus Vos: Reformed Biblical Theologian, Confessional Presbyterian is a cloth-bound volume wrapped in a glossy dustjacket bearing an original portrait. After Camden Bucey’s forward, the text begins with a detailed account of Vos’s background growing up the son of a minister in Holland. The 317 pages of text are divided into fourteen chapters with each having subdivisions. Following the author’s acknowledgements at the end there is an index but unfortunately no bibliography. Reformed Forum might consider providing a bibliography via download from their website; it would give readers not only source information but could also serve to promote the book.

Briefly, Geerhardus was born to Reverend Jan Hindrik and Aaltje Beuker Vos in Heerenveen, Friesland, March 14, 1862. Jan had been raised German Reformed but his ministry was with the Reformed Dutch (a general term used for convenience but the reviewer recognizes it does not do justice to all the Dutch that are Reformed). Over the years Jan changed calls and the family moved, but all were in the context of Dutch influences until later years. Olinger explains the steps in Vos’s education in his homeland before moving to America for study at the Theological Institute, Grand Rapids, where he also taught as a student. He entered Princeton Seminary in September 1883 with the second-year class. The faculty included: A. A. Hodge, C. Wistar Hodge, James C. Moffatt, C. A. Aiken, Francis L. Patton, and most importantly for Vos, Professor of Old Testament William H. Green. Vos’s senior paper so impressed Green that he influenced a publisher to issue it bearing the title, The Mosaic Origins of the Pentateuchal Codes. The work shows Vos’s concern to defend Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch in an era when source criticism was increasingly challenging the divine origin and authenticity of Scripture. After studying Hebrew in Berlin and earning the PhD from Strasburg, Vos returned to teach at the Theological Institute but became frustrated with the low academic standards. He returned to Princeton to teach after persistent requests by Green. Vos became Professor of Biblical Theology in 1893 and then the following year married Catherine Smith in Grand Rapids. The couple settled into life in Princeton. Vos taught nearly forty years retiring in 1932 and then died August 13, 1949 with his memorial service held in Grand Rapids at Calvin College. He maintained friendships with Herman Bavinck and Abraham Kuyper in the Netherlands, but contact with Kuyper waned as he became increasingly involved in politics.

During Vos’s life in Princeton he was often seen walking the campuses of the seminary and university. He made friends in addition to Green, such as B. B. Warfield who was his closest colleague and confidant. Vos and Warfield often walked the village chatting as they watched the squirrels cavorting on the grounds. When Warfield had the heart attack that led to his death, he was on the Vos property. Another friend was Woodrow Wilson who arrived at the university in 1890 to teach and then was its president, 1902-1910. If this trio walked together it made for an interesting mix—a Kentucky theologian who had bred cattle, hunted quail, and was not only a polemicist-professor but a hymnwriter; a progressivist politician whose father, Joseph R. Wilson, was the stated clerk of what is often called the Southern Presbyterian Church; and then there was Dutch American Vos, who, according to Olinger, was retiring and more comfortable in casual situations.

Vos’s inaugural lecture to the professorship of biblical theology at Princeton Seminary is titled, “The Idea of Biblical Theology as a Science and as a Theological Discipline” (1894). Six years earlier B. B. Warfield’s inaugural discourse was “The Idea of Systematic Theology as a Science.” The two friends agreed they were scientific theologians. Olinger quotes the definition of biblical theology presented by Vos in his lecture.

Biblical Theology, rightly defined, is nothing else than the exhibition of the organic progress of supernatural revelation in its historic continuity and multiformity. (80)

Notice here the use of “supernatural” because the term biblical theology had been tainted from use by critical-liberal theologians that viewed Scripture as the product of man and not God; biblical theology for them involved culling the words of God from a collection of ancient religious documents gathered in the Bible. Thus, Vos’s use of “supernatural revelation” particularly distinguished his biblical theology from that of the critics. If one asked for a definition of biblical theology today the response might be, “Biblical theology is the history of redemption,” or, “Biblical theology is the covenantal unfolding of God’s redemptive work,” but Vos’s definition is more encompassing because it included the whole Bible, “the organic progress of supernatural revelation.” All of Scripture, not just the facts and flow leading to Christ and his work are important because all words together constitute the Word. As noted by Olinger, 144, Vos would have preferred the discipline to be called “History of Special Revelation,” but in his preface to Biblical Theology, he reluctantly had come to accept biblical theology because “names become fixed by long usage.” However, Vos’s definition was not chiseled in stone because by the time Biblical Theology was published in 1948, less than a year before he died, his definition had changed (page 5, Biblical Theology).

Biblical Theology is that branch of Exegetical Theology which deals with the process of the self-revelation of God deposited in the Bible.

He then goes on to make four points explaining what he means by the word revelation—its historic progressiveness (with redemption part of the history); the embodiment of revelation in history; the organic nature of the historic process observable in revelation; and its practical adaptability. In over fifty years Vos refined his definition affirming the Bible is God’s word as he opposed changing liberal theological trends regarding the doctrine of Scripture. Note that “the organic process of supernatural revelation” in the former definition became “the process of the self-revelation of God deposited in the Bible” in the latter definition. In the first definition, he could speak generally of “supernatural revelation,” but it became important years later to speak of the “self-revelation of God” given in the Bible. Where supernatural describes God’s activity, such as the supernatural virgin birth of Christ, self-revelation expresses the Christ, the God-man, surely supernaturally born, but born to reveal the Son, fully God and fully man. Note that “process” ended with completion of God’s revelation of Scripture. The process is not continuing; God illumines a reader’s understanding to comprehend what He has definitively revealed in the Bible.

In addition to the biographical information, the author summarizes Vos well, with brevity and clarity. The main works addressed are Biblical Theology, Grace and Glory, Pauline Eschatology, Reformed Dogmatics, and Self-Disclosure of Jesus. As Bucey noted in the forward, Vos’s works are not easy to understand, so Olinger’s explanations are helpful. From the author’s presentation I concluded that if I were to suggest readings to someone interested in Vos, I would recommend Olinger’s book be read first, then the collection of sermons titled Grace and Glory, and for further information a copy of A Geerhardus Vos Anthology by Olinger, P&R, 2005, would provide selections of varying difficulty allowing the reader to pick and choose. I have found Vos helpful when I use the Scripture reference index to see his comments on a particular passage; it is not particularly scholarly nor does my method do justice to the extent of Vos’s thought, but I benefit from him because he often had insights unavailable in commentaries.

Barry Waugh

Notes— I originally said the header image of the Old Library at Trinity College, Dublin, was taken by me, but that is incorrect, I realized that I found it on the internet somewhere. Regarding the continued use of German see the challenges faced by one minister, William T. Sprole, while a similar experience regarding Dutch was addressed by John H. Livingston. My mention of the slow transition to English by some of the Dutch is not intended to be a criticism. If I relocated to Holland, I would go to an English-speaking church until I learned enough of the language to attend a Dutch church. I can see why the Dutch and Germans clung to their languages for so long given the many English-speaking churches available in America, so a desire to continue the language of one’s homeland is to be expected. An interesting review article by J. V. Fesko challenges the originality of Vos’s thought, “Who Lurks Behind Geerhardus Vos? Sources and Predecessors.” David F. Wells, editor, Reformed Theology in America: A History of Its Modern Development, Baker, 1997, has articles addressing the Princeton Theology, Dutch Reformed Theology, and Southern Reformed Theology.