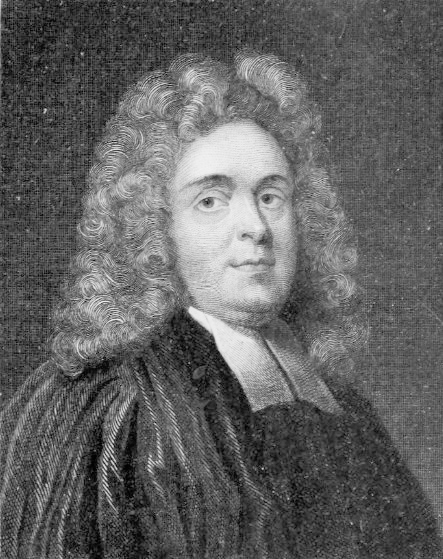

Matthew was born prematurely October 18, 1662, at Broad Oak, Flintshire, to Katharine and Philip Henry (1631-1696). His mother was the only child of Daniel Matthews; his father was the minister of the Worthenbury Church. The infant was baptized the day after he was born. It may seem unusual to baptize a child so shortly after birth but because of the high infant mortality rate parents often had their babies baptized as soon as possible. Given that Matthew was premature and weak, the mother and father sensed increased urgency.

Matthew was born prematurely October 18, 1662, at Broad Oak, Flintshire, to Katharine and Philip Henry (1631-1696). His mother was the only child of Daniel Matthews; his father was the minister of the Worthenbury Church. The infant was baptized the day after he was born. It may seem unusual to baptize a child so shortly after birth but because of the high infant mortality rate parents often had their babies baptized as soon as possible. Given that Matthew was premature and weak, the mother and father sensed increased urgency.

In May, just five months before Matthew was born, recently restored King Charles II enacted an Act of Uniformity to make the Church of England and its prayer book supreme in the land. Charles’s edict let all know that he was in charge of not only the kingdom but also its church. The Act of Uniformity required all ministers to affirm all of the Book of Common Prayer for ordination by the Church of England. They also had to renounce the Solemn League and Covenant. The act was a particular problem for Philip Henry because he was a loyal Presbyterian, a dissenter, ministering in a Church of England pulpit. In the first half of the seventeenth century, Presbyterians had hoped that England would become a nation with churches ruled by elders and not prelates, but the events of the Civil War years and Interregnum had not gone well for them. Pastor Henry’s refusal to comply with Charles’s act led to his dismissal from the Worthenbury Church October 27, 1661. Some historians say that Philip Henry was one of the dissenting ministers included in the more than two thousand removed from churches in the Great Ejection August 24, 1662.

The Family at Broad Oak

Matthew’s birth place, Broad Oak, was the ancestral home of his mother’s family and it was where he would live and return for visits during his later life. One biographer says the boy could read the Bible at the age of three and that he showed signs of great intelligence. When Matthew was about ten years old he survived a severe fever which his family had feared would lead to his death. After receiving preparatory education in a nonconformist academy, Matthew entered Gray’s Inn in 1685 to study for the bar, but as an adolescent he had professed faith in Christ in his father’s church and his interest soon turned from law to ministry. Henry had come to faith in Christ through a sermon preached by his father on Psalm 51:17, “The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit: a broken and a contrite heart, O God, thou wilt not despise.” He continued law studies for a time as he began the study of theology. Matthew’s early ministry was through occasionally supplying pulpits but as word of his expository ability spread, he was invited in the summer of 1686 to preach to a group of dissenters gathered in the home of a confectioner named Henthorne who lived in Chester. He continued preaching sermons in Chester and eventually received an invitation to be the congregation’s minister.

Before Matthew Henry could be ordained, he had a problem to resolve. His father was thoroughly convinced of presbyterian polity, but Matthew was not so sure. He struggled regarding whether he would adopt episcopal polity over prebyterian and become a bishop instead of an elder. One factor influencing his thinking was, according to Henry, Presbyterians recognized Church of England ordination but vice-versa was not the case. That is, he could always change to a Presbyterian church as a Church of England minister, which meant if he decided later to minister in a Presbyterian congregation, he could do so. There were other factors influencing his decision as Henry concluded his internal debate of the subject.

The doubt is not whether episcopal ordination be lawful, especially considering that the bishop may be looked upon therein as a presbyter in conjunction with his co-presbyters, (and the validity of such ordination is sufficiently vindicated by the presbyterians in their Jus Divinum [see notes]), but whether it be advisable or no? (Williams, 75)

Ordination by presbyters seems to me more regular and conformable to Scripture, and more becoming one that disowns a prelatical power. (ibid. 76)

That ordination by presbyters is (though not the only valid) yet the best, most scripturally regular, and, therefore, the most eligible, ordination. (ibid. 78)

Henry was convinced that a plurality of presbyters constituted the best church leadership, but he was not persuaded it was the only church government taught in Scripture. Having resolved his ordination dilemma, he wrote to some Presbyterian ministers in London that knew him well and asked them to ordain him. On May 9, 1687, Matthew Henry was examined for ordination having made a full “confession of his faith,” which was a statement of what he believed. As he expressed who God is in his confession he showed the influence of the Westminster Standards on his thinking by quoting from, without attribution, the Shorter Catechism, question 11, concerning providence. Henry’s examinations were sustained and he was ordained privately “by imposition of hands, with fasting and prayer” (Williams, 79). Why was he ordained privately? The history of Presbyterians in England was one of ups and downs because of the ecclesiastical polity sympathies of the reigning ruler, whether monarch or lord protector. It was a good idea always to be cautious when dissenting against the established church because rulers tended to readjust their thinking as the political situation changed. The Act of Indulgence had been issued by James II on April 4, a month before Henry’s ordination, which means the dangers of being a Presbyterian were somewhat alleviated giving dissenters more freedom. But the trouble was, individual bishops of the Church of England differed in their aggressiveness concerning enforcement of edicts from the king and if they had room enough to read between the lines of an edict’s text, they took full advantage of it by inserting their own interpretations and views. So, not only did the Presbyterians have to deal with unpredictable monarchs, they faced the challenge of some prelates with self-serving interests. Presbyterians did not know how things would play out regarding the Act of Indulgence and given their rocky history in England, it was wise to err towards caution. Presbyterian views played an important part in Matthew’s upbringing, but its significance has been lost by historians with one describing him as “an evangelical Church of England Minister,” another a “nonconformist minister,” and yet another said he was “a celebrated English nonconformist divine” (sources below).

Matthew Henry continued with the Chester congregation for twenty-five years during which time a church building was constructed. He was often sought to relocate and serve other pulpits, but it was not until 1712 that he accepted a call to the chapel in Hackney, London. In his later years Henry suffered of “the stone,” a disease which it seems nearly everyone in his day experienced especially if they were sedentary and studious. May 31, 1714, Henry left for a visit to Chester to see his former congregation and friends. While on his return trip to London he became paralyzed, possibly caused by a stroke, and he had to stop in Nantwich. It is reported he said to one of his friends as death approached, “You have been used to take notice of the sayings of dying men, this is mine, that a life spent in the service of God, and communion with him, is the most pleasant life that anyone can live in this world.” Henry worked faithfully sometimes preaching as often as seven times a week. After just a bit over fifty years of life, Matthew Henry died June 22, 1714.

Henry was married twice. His first wife was Katharine Hardware who died of small pox shortly after the birth of their first child. In remembrance of his deceased wife, Matthew named the infant for her mother but little Katharine lived only fifteen months before whooping cough took her life. Shortly thereafter Henry married Mary Warburton. The names of children given in Williams’s book are Elizabeth, Mary, Esther, Ann, Philip, Elizabeth, Sarah, Theodosia, and Mary. The absence of baby Katharine’s name indicates these were the children who survived to become adults. The repetition of both Elizabeth and Mary may indicate a fondness for the names; Henry was honoring ancestors with the same given names; or children that die are sometimes honored by naming a later infant with the deceased’s name. Of course, given Henry’s dedication to Christ, he may have found the mothers of both the Lamb of God and the one who announced his arrival particularly blessed.

Matthew Henry is known primarily because of his commentary on the Bible. The massive work shows his dedication to the systematic exposition of Scripture which he learned from the Puritans as taught to him by his father. It was his practice to systematically preach through Scripture which then provided exegetical information for his commentary series. Henry’s comments show his faithfulness to preach the whole counsel of God. Writing a commentary on the whole Bible is an ambitious project which Henry, unfortunately, was not able to complete. The book of Acts is the last portion he wrote before he passed away. The remainder of the New Testament was completed by other men using Henry’s notes (see Notes for a list of the writers). The date of publication of the first edition of Henry’s commentary titled, An Exposition of all the Books of the Old and New Testament: Wherein the Chapters are Summed up in Contents;…In Six Volumes, has proven elusive, but the third edition was issued 1721-1725 (maybe). Henry has been republished over the years in three, nine, and six volumes, as well as a single abridged version. A quick scan of the British Library shows about a dozen English editions. It is possible that Matthew Henry’s magnum opus is the most influential Bible commentary published since the Reformation because it has enjoyed use by a general Christian readership while works by John Calvin and Martin Luther have been used by the Reformed and Lutheran respectively. His other works were published in a collection titled, The Miscellaneous Works of the Rev. Matthew Henry, V.D.M. Containing in Addition to those heretofore Published, Numerous Sermons, now first Printed from the Original Manuscripts…[etc.], which includes a biography of his father, and it was published in two volumes in London by Joseph Ogle Robinson, 1833. There is also a set titled, The Select Works of the Late Rev. Matthew Henry; Being a Complete Collection of all His Treatises, Sermons, and Tracts, as Published by Himself; and a Memoir of His Life, two volumes, Glasgow: A. Fullarton & Co., 1833, which is possibly the same as the first two volume set but published beyond Hadrian’s Wall instead of London.

Barry Waugh

Notes—The header photograph was taken by the author from the walkway atop the ancient Roman wall around Chester. From its Tudor appearance, it must have existed in Henry’s day. Broad Oak, Flintshire, United Kingdom may be represented today in The Broad Oak which is a pub about twenty miles northwest of Worthenbury where Philip Henry was a minister (the oldest pub in England claims to date to the sixth century). The Broad Oak is about nine miles west of Chester. For more information about dissenters read on this site “Alexander Waugh, 1754-1827,” and the author of this site’s post on Place for Truth, “Lord, Have Mercy on Us,” which addresses the dissenter background of Daniel Defoe. The Act of Uniformity was enacted May 19, 1662. The publications excluding mention of Henry’s Presbyterianism are The New International Dictionary of the Christian Church, Concise Dictionary of National Biography (circa 1930?), and Cyclopedia by McClintock and Strong. Henry mentioned Jus Divinum which refers to Jus Divinum Regiminis Ecclesiastici, or The Divine Right of Church Government, by sundry Ministers of London, 1646. The book sets forth the case that presbyterian polity is the polity of Scripture, which is something Matthew Henry, as noted in the quote from him above, disagreed with. Matthew Henry’s commentary was completed by the following authors: Romans by Dr. John Evans; 1 Corinthians by Simon Browne; 2 Corinthians and the Thessalonian letters by Daniel Mayo; Galatians by Joshua Bayes, Ephesians by Samuel Rosewell, Philippians and Colossians by Dr. William Harris, 1 & 2 Timothy by Benjamin Andrews Atkinson; Titus and Philemon by Jeremiah Smith; Hebrews and Revelation by William Tong; James by Dr. S. Wright; 1 Peter by Zechariah Merrill; 2 Peter by Joseph Hill, the epistles of John by John Reynolds of Shrewsbury; and Jude by John Billingsley (Williams, Memoirs, vii). The primary biographical source used was Memoirs of the Life, Character, and Writings, of the Rev. Matthew Henry, by J. B. Williams, the third London edition, Boston: Pierce & Williams, 1830; the digital copy used for this post is from Samuel Miller Breckinridge’s copy on Internet Archive. Williams’ text, page 215, refers to Note J at the end of the book on page ix. It reads, “Mr. Henry left a widow and seven surviving children. Mrs. Henry continued after her husband’s death many years. Her decease is thus noticed by her excellent sister-in-law, Mrs. Savage. August 12, 1731. Thursday morning dear sister Henry began her everlasting rest. To her a merciful release, having been seven months confined. She was in her sixty third year. His issue by the first marriage was a daughter, Katharine, born February 14, 1689. She married Mr. Wittar, of Bomborough, in Wirrall; afterwards Mr. Thomas Yates, of Whitechurch; and lastly Mr. John Ravenshaw, of Whitchurch. By the second marriage she had nine children, three of whom died in his life-time.” This article has been revised from the original one posted April 2019.