Caspar Wistar was born in Princeton, Feb. 21, 1830, to Sarah Bache and Charles Hodge. Sarah was a descendant of Benjamin Franklin on her mother’s side. As a lad, Wistar enjoyed living in the Hodge House on the seminary campus in the midst of student life and academics. In his memorial for C. W. Hodge, Francis L. Patton said that Wistar, was a “quiet, reticent, studious boy.” After attending school for a time he accepted J. A. (Addison) Alexander’s offer to tutor him privately learning “English grammar through…study of the Greek language.” Addison was not only Wistar’s teacher but also a friend. Addison composed for a few years a custom serial of stories for his young colleague titled “Wistar’s Magazine”. In a letter written by Addison from his home “Breckin Ridge” in Princeton to young Wistar during a visit to Philadelphia, he responded to the boy’s willingness to pick up anything Addison needed. Addison’s only request to the responsible youth was to stop by Odgen & Brother Merchant Tailors at 110 Chestnut Street to see if they had anything for him, which if so, could be sent either to Wistar’s Uncle Hugh or to Princeton via boat.

Caspar Wistar was born in Princeton, Feb. 21, 1830, to Sarah Bache and Charles Hodge. Sarah was a descendant of Benjamin Franklin on her mother’s side. As a lad, Wistar enjoyed living in the Hodge House on the seminary campus in the midst of student life and academics. In his memorial for C. W. Hodge, Francis L. Patton said that Wistar, was a “quiet, reticent, studious boy.” After attending school for a time he accepted J. A. (Addison) Alexander’s offer to tutor him privately learning “English grammar through…study of the Greek language.” Addison was not only Wistar’s teacher but also a friend. Addison composed for a few years a custom serial of stories for his young colleague titled “Wistar’s Magazine”. In a letter written by Addison from his home “Breckin Ridge” in Princeton to young Wistar during a visit to Philadelphia, he responded to the boy’s willingness to pick up anything Addison needed. Addison’s only request to the responsible youth was to stop by Odgen & Brother Merchant Tailors at 110 Chestnut Street to see if they had anything for him, which if so, could be sent either to Wistar’s Uncle Hugh or to Princeton via boat.

After completing his program in Princeton College in 1848 with highest honors, even though his earliest interest was in studying medicine—likely due to influence from or admiration for his uncle Hugh—Wistar instead entered Princeton Seminary in 1849. He completed his studies in 1853. The additional year required for completing his program was likely due to the need to work for funds. He tutored students at the college and like his friend Addison, he taught for a short time in the Edgehill School. He was licensed by the Presbytery of New Brunswick, 1853, and then on November 5 of the following year he was ordained by the Presbytery of New York. His first call was to the Ainslie Street Presbyterian Church, Williamsburg (Brooklyn), New York, where he ministered for one year as stated supply followed by a two-year pastoral call. In 1856, he moved his ministry across the Hudson River and then the Delaware to the pulpit of the Presbyterian Church in Oxford, Pennsylvania. His second call was a little longer than his first ending in 1860 with his return to Princeton.

Wistar’s homecoming came at a great cost to himself and the seminary community because the position he was to take was available due to the death of his close friend, Addison Alexander. According to an announcement in The New York Times, September 19, 1860, Wistar was to be inaugurated the first Thursday in November with Dr. McPhail, president of Lafayette College, preaching the sermon; Dr. Phillips of New York propounding the questions; and Wistar, as was the custom for faculty, delivering his inaugural lecture. However, his lecture was not published because the copy requested by the board for that purpose was not ever received. His return meant that he joined the faculty with his father, Charles, and brother, A. A. Hodge, making for three teaching Hodges on campus just as at one time there had been three faculty from the Alexander family.

Professor of New Testament History and Biblical Greek C. W. Hodge had a tough job ahead of him. He had to try and fill Addison’s shoes which would be extremely difficult given his incomparable intellect. Even the General Assembly had recognized its daunting task commenting that finding Addison’s replacement was “beyond all human power.” Addison had taken to languages like a duck to water; it is believed he knew as many as thirty including not only European and Semitic languages but even more difficult ones such as Chinese. Though an intelligent man, Wistar, was surely not an intellectual doppelgänger of Addison. Not only was filling the classroom position of his predecessor an intimidating prospect but there were also some changes taking place in the Princeton faculty. The General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA) in 1860 had divided A. T. McGill’s professorship in two and established a new chair. Professor of Ecclesiastical History and Church Government McGill continued as such, while his previous practical divinity duties were assigned to the new Chair of Pastoral Theology and Sacred Rhetoric to which Benjamin Morgan Palmer of First Presbyterian Church, New Orleans, was elected but then turned down. There are always challenges when one enters a new job, but in the case of C. W. Hodge, he had a bit tougher row to hoe.

Wistar Hodge was a diligent, thorough, and dedicated but sometimes obsessive professor. Patton commented in his memorial that he “did not scatter his energies. He was not engaged in various pursuits.…His department was New Testament and he kept rigidly to it.” His meticulous study and attention to detail were evident in the sixteen thick octavo volumes of manuscript notes penned fastidiously. Included in these volumes were notes on the New Testament canon, the life of the Lord, and the history and literature of the apostolic church. With respect to exegetical curricula, the volumes included his thoughts on the Gospel of John, 1 Corinthians, Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, and Hebrews. He was an acceptable speaker inspiring some of his students but his tedious method was not every student’s cup of tea. His lecturing voice was adequate but could have been enhanced with some modulation and the use of gestures for emphasis. His lecture notes were almost entirely the extent of his writing because he did not publish even though he was often encouraged to do so. He did not write for journals, not even the seminary’s publications.

On a personal level, just as he had been when a child, Wistar was one who preferred being alone for contemplation and introspection, which made him appear antisocial and unconcerned about others. Patton hints in his memorial that Wistar could sometimes be a bit difficult to get along with and was interested only in himself. But his brother, A. A. Hodge, said of him, “Wistar will never let you know that he cares for you, but if you were in trouble, or one of your children was sick, he would do more for you than anybody in Princeton.” Patton said that Wistar’s “life was singularly uneventful and there is something almost pathetic in its quiet, even flow,” to which he added that he “was contented to live alone, think alone, and hold his convictions in unshared solicitude and in the calm confidence that he was right.” If Wistar preferred solitude it was not the solitude of bachelorhood. Paul Gutjahr has written that Wistar married three times. His father, Charles, married Mary Hunter Stockton when his first wife, Sarah Bache, died. Wistar’s first marriage was to his stepmother’s daughter from her first marriage who also was named Mary Hunter Stockton. Sadly, after only a few years, Wistar’s Mary died of consumption. Then, he married again about five years later, but once again, this time after only about a year, his second wife, Harriet Terry Post, died of consumption. The third marriage to Angelina Post in 1869 was long and happy and was blessed with the birth of two children. If Wistar preferred solitude, why did he pursue marriage at all, especially after one heartbreaking death, then another? He had two opportunities to continue as a widower but preferred marriage.

As Dr. C. Wistar Hodge drew near to the end of his life there was a move in the PCUSA to revise the Westminster Confession of Faith. The leader of those against the revisions at Princeton, though he himself was not opposed to the concept of revision just the particular way it was being attempted, was B. B. Warfield. New Brunswick Presbytery, the presbytery of the seminary faculty, had voted against the revisions sent down by the Assembly of 1889. The faculty were unanimously opposed, including Wistar. Dr. Patton commented in his memorial regarding Wistar’s view.

He believed in the plenary inspiration of the Scriptures, and was a Calvinist of a type perhaps a little higher than his father. He was not in sympathy with the agitation in favor of the revision of the Westminster Confession. It was not because he felt that in minor statements it was incapable of improvement, but because he knew that our terms of subscription were liberal enough to remove every burden from the conscience of any man who heartily believed in generic Calvinism. He also felt, as others did, that it would be hard to arrest a movement after it had begun; and, moreover, that while older men might be satisfied with a softening of the harder lines of Calvinism, there would be no inconsiderable number of younger men who would be willing to see the Calvinistic elements eliminated. (56-57)

It is an interesting quote especially since Patton described Wistar as more committed to Calvinism than his father, Charles Hodge. The use of the words “generic Calvinism” would imply less than a commitment to full subscription, though “generic” may be Patton’s perspective on Wistar’s view. The mention of the snowball effect revision might have upon the integrity of the Confession as one change led to another has been and is a considerable objection. There had already been a revision earlier in the 1880s which removed a sentence regarding near-kin marriages from chapter 24 of the Confession, so maybe the ball was already rolling. The denomination would go on to revise the confession in 1903 despite continued opposition; the changes included adding chapters entitled “Of the Holy Spirit” and “Of the Love of God and Missions,” revising a few portions of chapters of its text, and including a statement weakening its teaching on the doctrine of election.

According to Dr. Patton’s memorial, Caspar Wistar Hodge died of an extended illness involving a high fever on Sunday, September 27, 1891. However, there is disagreement among the newspapers regarding the specific cause of death because it was attributed to three different illnesses–throat cancer, heart disease, and lung disease. Maybe the latter is the best choice for a cause if Dr. Patton’s mention of the high fever is accurate. Dr. Hodge’s funeral was held in the Presbyterian Church in Princeton, September 30, 1891. The trustees, directors, faculty, and students of the seminary along with faculty and friends from the college formed a processional to the church for a brief service. President of the Board of Directors Abraham Gosman, D. D., read selections from Scripture, and Dr. William Henry Green of the seminary faculty prayed. Everyone then walked the few blocks to the Princeton Cemetery where Dr. Patton led the grave-side service. Later, Patton’s memorial was delivered in a special service at the Presbyterian Church on Sunday morning, November 15. Wistar was survived by his wife, Angelina Post, their daughter, Mary, and their son C. W. Hodge, Jr. who would follow in his father’s footsteps teaching in the seminary.

Dr. C. W. Hodge was honored by Princeton University with the Doctor of Divinity, 1865, and the Doctor of Letters, 1891. As was mentioned, he was not one to publish, but there are a few titles to mention and even these are mostly special purpose works. The pamphlet titled, A Sermon Preached in the United Congregational Church, Newport, R. I., Sunday, September 25, 1881, by Rev. C. Wistar Hodge, D. D., was likely published by the church mentioned in the title. The syllabus, New Testament Criticism, Lectures by Dr. C. W. Hodge, Before the Junior Class, Princeton Theological Seminary, Collated from Phonographic Notes by W. J. Frazer, with Syllabus Prepared by Dr. Hodge, 1880, was likely printed as a convenience for student use because the title page notes that the book was “Printed not Published.” Also, Syllabus of Lectures on Apostolic History and Literature, Printed for the Use of the Senior Class in Princeton Theological Seminary, 1887, and Syllabus of Lectures on the Gospel History, Printed for the Use of the Middle Class in Princeton Theological Seminary, Princeton, 1887, appear to have been done for student class use but in a more formal form.

For a closing thought, Wistar Hodge’s love of privacy, circumspect studiousness, and possibly temperamental personality, if added to his reluctance to roll the presses to distribute his writings combine to give reason for his anonymity. He taught in Princeton Seminary for thirty-one years exceeding some of the more well-known professors such as his friend Addison by six years, Addison’s brother James Waddel by twenty-nine years, and Wistar’s brother Archibald Alexander Hodge by twenty-three years. In Alfred Nevin’s Encyclopedia of the Presbyterian Church, 1884, Addison, James, and Archibald all have biographies, but guess who is missing, Wistar. A key factor for the anonymity of Wistar is that all three of these professors were well published.

Barry Waugh

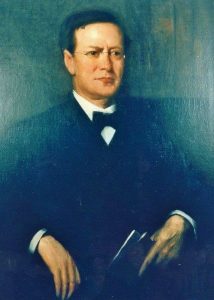

Notes–The header shows the Hodge House on the PTS campus. The porch on the left accesses a door that was installed so students could enter the professor’s study without disturbing the family by using the front door. As a child, it seems C. W. Hodge was known as “Caspar,” at least Addison Alexander addressed his letter to him using that name, but as an adult “Wistar” came to be the name of choice with his name in printed documents, “C. Wistar Hodge.” Some sources have Wistar’s second wife’s middle name as “Perry,” but others, including the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP), have “Terry.” I have used “Terry,” as given in the HSP archival finding aid titled, The Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Collection 3117, Friends of Franklin, Inc., Descendants Project Record, 2009, which is in PDF at the HSP site. Addison’s home “Breckin Ridge” was then on what was still called Steadman Street but is now known as Library Place. It was built in 1836 for John Breckinridge—hence the name of the house—when he moved to Princeton from Philadelphia to take up his professorship in Pastoral Theology and Missionary Instruction. It originally stood at a slightly different location on Steadman Street and was moved to its current location in the 1880s where it was lived in by Woodrow Wilson. The memorial referred to was a primary source for this biography and its bibliographic information is, Francis L. Patton, Caspar Wistar Hodge, A Memorial Address, New York: Anson D. F. Randolph & Co., [1891]. See Paul Gutjahr, Charles Hodge: Guardian of American Orthodoxy, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011, regarding Wistar’s marriages, page 280. Gutjahr has a genealogical diagram for the Hodge family and a collection of biographical vignettes and sketched portraits for many of the personalities mentioned in his book. The information about the Old School PCUSA General Assembly meeting of 1860 is from the minutes. David B. Calhoun’s two volumes titled, Princeton Seminary, 1994, 1996, were consulted. The picture of the current appearance of the Hodge House is the authors. The portrait of Wistar, the explanation of Addison Alexander’s use of “Breckin Ridge,” the information about Wistar not having his inaugural lecture published, and the letter of November 25, 1843, from J. A. Alexander to Caspar Hodge were all generously provided by Ken Henke, Special Collections, Princeton Theological Seminary. The newspapers viewed on the Library of Congress’s digital periodical site regarding the cause of death were The New York Times, Sept. 25, 1891, which reported a few days before his death that he was “very ill with throat cancer”; the Evening Capital Journal, Sept. 29, 1891, Salem, Oregon, reported that he died of “lung disease”; and finally, The Los Angeles Herald, Sept. 28, 1891, said he died of “heart disease.” The information about the funeral proceedings is from The New York Times, Oct. 1, 1891. Family information was located in The Wistar Family, A Genealogy of the Descendants of Caspar Wistar, Emigrant in 1717, by Richard Wistar Davids, Philadelphia, 1896. Wistar’s second and third wives had the same last name but were not sisters, however they were cousins as in, The Post Family, by Marie Caroline de Trombriand Post (Mrs. Charles Alfred Post), New York: Sterling Potter, 1905.