In a few days the Reformation will be celebrated once again. For this post a mix of items relevant to Scotland and the Reformation are provided. The most significant is a brief presentation of Stirling Presbytery Records 1581-1587.

Header Image

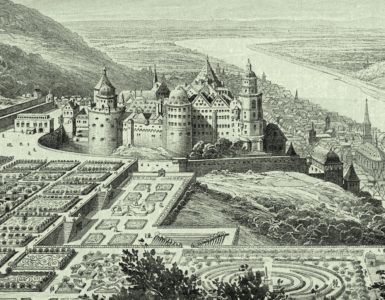

The National Library of Scotland has several hundred digital maps dating 1558-1947 with about two hundred selections composed before 1800. The map portion in the header is from “The Kingdome of Scotland” by John Sudbury and George Humbell, 1610. The original map measures 14.45 x 17.95 inches (367 x 433 millimeters). On the left and right sides of the map are pictures of King James of Great Britain, France & Ireland; Henry, Prince of Wales & Ireland; Anne, Queen of Great Britain, France and Ireland; and Charles Duke of York and Albany. It is scaled with Scottish Miles which is equivalent to 5,962 English feet. The selection is a beautiful example of cartography that presents Scotland at a transitional point in its history with King James of Scotland ruling Great Britain. During his reign the Authorized Version (KJV) was published.

Presbytery Records

Antiquarian presbytery records are difficult to find for American Presbyterianism and records for the Kirk in Scotland are even less accessible here in the States, but the Scottish History Society published in 1981, Stirling Presbytery Records 1581-1587, as edited by James Kirk. Dr. Kirk’s introduction is informative as it provides perspective, context, and summary of the records. In 1581 the General Assembly resolved to establish thirteen presbyteries. Scotland is just over 30,000 square miles in size which makes it just a bit smaller than its comparable state, South Carolina. Stirling Presbytery was first convened August 8, 1581, by Robert Montgomerie and Andro Grahame who had been appointed by the Assembly. Eight ministers and nine elders were present. In the records Stirling is spelled “Strivling” and on the map the fort is spelled “Sterling” while the region is “Striueling.” This spelling difference is indicative of variations in the minutes which include words from and derivatives of Latin, Gaelic, Old Scots, and English words as well as a few in French. Some portions of the transcription are challenging. For example, the quote that follows is from a list of charges against a minister with the given name James.

Thridlie, being accusit for mareing of ane Agnes Kidstoun (hir husband [blank] beand on lyf and na divorcement passit betuix thame) with ane Johnne Broun, the said James confessit the mariage, bot denyit that he knew hir first gudman to be on lyve.

Modernized the statement reads as follows:

Thirdly, accused of marrying Agnes Kidstoun (her husband [space for his name] is still alive and they are not divorced) with Johnne Broun. The said James confessed [doing] the marriage, but denied that he knew her first husband was alive.

All the minutes were not read for this article. The selection read extends from August 1581 to April 9, 1583. Note that if you decide to read the minutes, the new year began on March 25. The issues before Stirling Presbytery were overwhelmingly concerned with marriage. There are cases of bigamy; at least two cases of paternity; one case of a wife either not consummating her marriage or breaking her betrothal; children born because of fornication or adultery; how baptism was to be handled when a child was born from a sinful relationship whether adultery or fornication; and one case that was called adulterous until the man proved he was not married at the time he had relations with the single woman in question, thus yielding fornication rather than adultery. At some meetings as many as four or five new or continuing marriage cases were addressed. Some of the people repented, but others did not. Excommunication was common and the policy was anyone excommunicated could not be spoken with by members in good standing; the excommunicated were ostracized. In the case of discipline administered to Robert Montgomerie (Montgomery), the same minister involved in organizing Stirling Presbytery and pastor of the Stirling church, considerable time was spent dealing with discipline of him including dereliction of duty, theological issues, and other charges that eventually ended up in his excommunication (for more see, Dictionary of Scottish Church History & Theology). Two men were confronted for having spoken with Montgomerie socially and they both repented. One might think there would have been several cases of Sabbath violation, but of the records read, there was only one case and it occurred towards the end of the section. One of Stirling Presbytery’s duties was admission of ministers to their churches but in a few cases admissions were delayed due to inability of transferees to obtain their credentials in time. Stirling Presbytery reviewed church records and presbyters would informally visit churches, but the practice was formalized as a practice in April 1583 when presbyters were first appointed to visit churches regularly. Also, visitation occurred when an issue arose in a church as was the case when a minister complained that his congregation would not provide him a livable house.

The presbytery meetings themselves were different from what one would see today. The moderator was elected to serve a six-month term and it appears meetings were held as needed—i.e. called meetings in today’s terminology. It might be thought that a moderator would lead three or four meetings during his tenure, but for the six months extending from August 8, 1581 there were twenty-three meetings yielding nearly weekly gatherings. Often, there were only one or two actions, so meetings could be brief. Considering the map above, Dunblain, which is close to Sterling, became its own presbytery, so it can be seen presbytery bounds were small, and in some cases, isolated. Presbyteries were made up of several parishes served by the individual churches. Going to a presbytery meeting meant presbyters did not have to travel more than a few miles. It does not appear the Kirk was so concerned about the bounds of presbyteries as it was about their centers; whether an area without a church was within presbytery bounds was not significant because if a new church in a new region was established, others would follow yielding a center for a new presbytery. An interesting practice was when elders attended presbytery for the first time, they were sworn in as commissioners. Another practice for a short time was each minister would tell his fellow presbyters what his current preaching series was about. It was often noted that presbytery was acting at the instruction of the General Assembly and there were decisions resulting from adoption of the Second Book of Discipline in 1578. The tendency is to think that presbytery meetings have always been pretty much as they are now, but reading the old Stirling records shows that things have changed over four centuries.

If you are interested in how the presbytery as we know it developed, it would be worthwhile to read James Kirk’s transcription of the records of Stirling Presbytery. In some places, it can be difficult to figure out what is being communicated, but I found that skipping over the cryptic and going on to the more interpretable was the best approach. Marking the cryptic portions in some way to return for a new reading after more experience with the records is an effective method.

The following are a few links regarding John Knox

For John Knox from a different perspective see Wayne Sparkman’s “The Love Life of John Knox (1564): Considering the first and second marriages of John Know,” published in 2014 on the Aquila Report.

The Edinburgh Tourist site has a page and a nicely done 7.5 minute video about the “John Knox House.” The house includes access to the rooms, a Reformation museum and book room, as well as a gift shop. His house is the oldest surviving Medieval house in Edinburgh.

John Knox’s church in Edinburgh is St. Giles’ Cathedral.

Finally, watches were a recent invention when John Knox obtained his watch made by Frenchman Nicolas Forfaict. A photograph of the watch held by the University of Aberdeen’s Museums and Special Collections is provided.

Barry Waugh