Joachim Neander was born at Bremen, Germany, 1650. His father was a teacher in the local Latin school until he died when Joachim was sixteen years old. After his father’s death, he entered the Reformed University at Bremen to study theology in order to become a minister. At the time, he viewed the ministry as nothing more than a profession that would provide for a good future and job security. However, growing in influence at the time was a movement in Germany called pietism which believed the existing Protestant churches in the land, both Lutheran and Reformed, over emphasized doctrine at the expense of personal experience and practical Christian living.

Joachim Neander was born at Bremen, Germany, 1650. His father was a teacher in the local Latin school until he died when Joachim was sixteen years old. After his father’s death, he entered the Reformed University at Bremen to study theology in order to become a minister. At the time, he viewed the ministry as nothing more than a profession that would provide for a good future and job security. However, growing in influence at the time was a movement in Germany called pietism which believed the existing Protestant churches in the land, both Lutheran and Reformed, over emphasized doctrine at the expense of personal experience and practical Christian living.

James I. Good expressed the situation as follows:

Two causes led to the development of Pietism in the Reformed Church in the close of the seventeenth century. The first was a reaction against the dead orthodoxy and formalism that had crept into the Church. The second was the rise of the Cocceianism, or the Federal School of Theology. The two really were one, Cocceianism a reaction against deadness of doctrine, and Pietism a reaction against deadness of life. Through the theological controversies religion had become a matter of the head, rather than of the heart and life (314-315).

Pietism first began among the Lutherans then spread to the Reformed Church. One Sunday in the fall of 1670, Neander went to hear Theodor Untereyck (1635-1693) preach with the intention of making fun of his teaching, however, he instead found himself convicted of his hardness and folly as he came to faith in Christ. After the service he left the church and mentioned to the two friends with him that he had decided to follow Christ. From then on, Neander attended Untereyck’s services and became a follower of his teaching. Neander’s ideas concerning life and the ministry had changed entirely.

The spring of 1671, Neander accepted an offer from some French Reformed (Huguenot) families in Frankfurt to take their five sons about sixty miles south in Germany to the University of Heidelberg. It was not unusual for parents with means to hire someone to oversee their boys and keep them out of trouble while away at college. It was a good opportunity for Neander because he could study according to his own interests as he tutored and chaperoned the boys until they returned to Frankfort in 1673.

Continuing with his pietist interest, the next year Neander participated in private Bible study and prayer meetings in Frankfurt led by Philipp Jakob Spener (1635-1705). Spener opposed what he believed were the rigid organization and doctrinal inflexibility of Lutheranism while he also condemned the lax morality of many clergy. Neander became more deeply associated with the pietist movement and found in Spener the teaching that continued Untereyck’s influences from his past. Joachim Neander’s most significant work during these years in Frankfort was writing hymns. As the pietist movement grew it increasingly included Reformed as well as Lutheran Germans. The Lutherans sang Neander’s hymns in prayer meetings and as pietism came to influence the Reformed they too sang his hymns as they became less committed to Psalmody.

In 1674, Neander became headmaster of the parochial school started by the Reformed Church in Dusseldorf and he assisted its minister, surnamed Lursen, with duties even though he was not officially an assistant. Neander was still a theological student and he would continue as such until his death; his status seems to correlate with the current definition of Presbyterian licensure which allows ministerial work under judicatory oversight. Giving boost to the pietist movement, in 1675, Spener published, Pia Desideria (Pious Desires), which became the manual for pietist practices as the movement would spread on beyond Germany and the Netherlands into Scandinavia. Neander and Lursen worked well for a time but as the former became more popular with the congregants, the latter came to resent his colleague. Lursen, it is believed, began speaking ill of Neander and his theological views. Added to this tension between the two was Neander refused to adopt the order of the Reformed Church and he would not subscribe to the Heidelberg Catechism. He was censured by the Presbyterium (similar to a presbytery) in October, 1676, and added to the charges concerning his church ministry were accusations regarding his operation of the school. At the school he had developed curriculum and did not seek its approval by the Presbyterium; he rescheduled examinations without approval; and he made repairs on the property without approval. These were the main points against him. So, the Presbyterium presented a declaration to Neander, February 3, 1677, suspending him from directing the school and forbidding him from preaching in the church. The declaration required him to subscribe to the Heidelberg Catechism and the order of the Reformed Church; condemn attempts to separate from the church as in pietist conventicles; and promise not to hold private prayer meetings without first having the approval of either the pastor or the Presbyterium. The issue for Neander was simple—would he work within the Reformed Church and submit to its standards? Having been admonished by the brethren, he signed the declaration and was allowed to return to his duties.

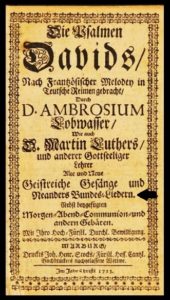

Neander was allowed to resume teaching the students in the school in Dusseldorf, while in the church, there would be a change. Perhaps seeing the handwriting on the wall or simply unable to continue, Lurson resigned June 1677. Within months Neander accepted an opportunity to assist in St. Martin’s church, Bremen, 1679, where his mentor Untereyck was pastor with Cornelius de Hase, who was also professor of theology at Bremen University. The new call was a return to the church where Neander had committed himself to Christ. He began July 1679 with his duties including occasional preaching, filling in if Untereyck or de Hase were sick, and leading the services held at 5:00 in the morning on the Lord’s Day. Neander published the first hymn book of the Reformed Church of Germany Hymns of the Covenant, 1679. The Reformed churches had worshiped historically singing the Psalms, and it was Neander’s hymns that contributed to the change from exclusive Psalmody. Neander followed the Reformed custom of printing the melodies with the hymns and composed some of the melodies himself, as Luther had done.

Neander was allowed to resume teaching the students in the school in Dusseldorf, while in the church, there would be a change. Perhaps seeing the handwriting on the wall or simply unable to continue, Lurson resigned June 1677. Within months Neander accepted an opportunity to assist in St. Martin’s church, Bremen, 1679, where his mentor Untereyck was pastor with Cornelius de Hase, who was also professor of theology at Bremen University. The new call was a return to the church where Neander had committed himself to Christ. He began July 1679 with his duties including occasional preaching, filling in if Untereyck or de Hase were sick, and leading the services held at 5:00 in the morning on the Lord’s Day. Neander published the first hymn book of the Reformed Church of Germany Hymns of the Covenant, 1679. The Reformed churches had worshiped historically singing the Psalms, and it was Neander’s hymns that contributed to the change from exclusive Psalmody. Neander followed the Reformed custom of printing the melodies with the hymns and composed some of the melodies himself, as Luther had done.

Joachim Neander was not permitted to live long because his work was barely started before it was completed. Within a year of publishing Hymns of the Covenant he became very ill for several days before dying, May 31, 1680. During his decline he found encouragement and assurance when Hebrews 7-10 was read to him with the chapters’ emphasis on the superiority of the New Covenant over the Old. His last words were Isaiah 54:10.

For the mountains shall depart and the hills be removed, but My kindness shall not depart from thee, neither shall the covenant of My peace be removed.

The day of Pentecost was the day of his death. He had been called to Bremen on the same day of the year, the previous year. Untereyck preached on the following Sunday a memorial sermon from the third chapter of John.

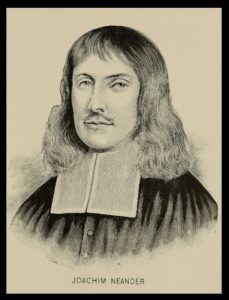

Neander wrote many hymns but popular with Reformed folk is “Praise to the Lord, the Almighty,” (53, red Trinity Hymnal) which was the hymn I sang with the congregation this past Sunday morning as we began worship. When I saw Joachim Neander’s name at the bottom of the hymnal page once again it prompted me to refresh what I knew and learn more about him. His life shows that even when the Christian wanders, the grace of forgiveness leading to renewal of purpose can lead to beneficial ministry. There is a portrait of Neander in Dusseldorf that has written beneath it, “Immovable in the Lord.” For a short life of but a score and ten years, he was a good servant.

Barry Waugh

Notes—The header is from Wikimedia Commons as found in, H.F. Helmolt, History of the World, Volume VII, Dodd Mead 1902, picture is between pages 290 and 291; Heidelberg Castle had some of its foundations laid in the 11th century and was destroyed by fire after struck by lightning in 1764. The Psalms and hymns title page arrow aligns with Neander’s Life and Songs, which shows his importance for the Reformed Church in 1723. The primary source and the sketched portrait were taken from James I. Good, History of the Reformed Church of Germany, 1620-1890, Reading: Daniel Miller, 1894, 344-362. J. H. Dubbs, “Early German Hymnology of Pennsylvania,” Reformed Quarterly Review 27, issue 4, Oct. 1880, 504-524. E. E. Ryden, “Joachim Neander: The Gerhardt of the Calvinists,” in The Story of Christian Hymnody, Rock Island: Augustana Press, 1959, pp. 109-114. William J. Hinke, “The Early German Hymn Books of the Reformed Church in the United States,” Journal of the Presbyterian Historical Society 4, no. 4 (Dec. 1907), 147-161; this article describes the first seven hymnbooks, 1753-1842, with their translated German titles followed by brief comments. Also, written in German is, Reinholdus Vormbaum, Joachim Neander’s Leben und Lieder (Joachim Neander’s Life and Songs), Elberfeld: Martini & Grüttesien, 1860. The only other hymn by Neander in the red Trinity Hymnal is, “Wondrous King All Glorious,” 166.