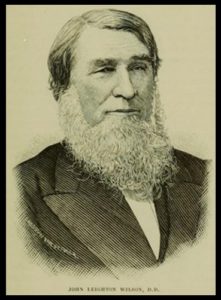

John Leighton Wilson (1809-1886) was born, raised, and schooled in Sumter County, South Carolina, then completed his formal education at Union College, Schenectady, before studying for the ministry in the first graduating class of Columbia Theological Seminary. He was ordained by Harmony Presbytery to be a missionary to Africa with the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM). He worked first at Cape Palmas then the Gaboon region for a total of nineteen years before returning to the United States. He was Secretary of the Board of Foreign Missions for the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, Old School, 1853-1860, and then he held the corresponding position for the Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS), 1861-1885. He was a respected missionary, minister, scholar, author, and linguist. His most significant work for readers of English is likely Western Africa: Its History, Condition, & Prospects, 1856; New York: Harper Brothers, 1856, London 1856.

John Leighton Wilson (1809-1886) was born, raised, and schooled in Sumter County, South Carolina, then completed his formal education at Union College, Schenectady, before studying for the ministry in the first graduating class of Columbia Theological Seminary. He was ordained by Harmony Presbytery to be a missionary to Africa with the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM). He worked first at Cape Palmas then the Gaboon region for a total of nineteen years before returning to the United States. He was Secretary of the Board of Foreign Missions for the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, Old School, 1853-1860, and then he held the corresponding position for the Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS), 1861-1885. He was a respected missionary, minister, scholar, author, and linguist. His most significant work for readers of English is likely Western Africa: Its History, Condition, & Prospects, 1856; New York: Harper Brothers, 1856, London 1856.

Wilson’s more than five-hundred pages making up Western Africa describes the region in detail by providing history, accounts of colonization (both by nations and for relocating freed slaves), a catalog of natural resources, descriptions of the indigenous peoples, observations of the fauna and flora, and of course, an account of his ministry bringing the light of the Gospel to the Africans. It may be surprising that Wilson would be interested in sciences such as botany and zoology, however science was the up-and-coming discipline in the antebellum nineteenth century, so educated individuals including ministers, found scientific books and discoveries interesting. Wilson’s observations published in Western Africa were beneficial not only for orienting new missionaries about their fields of service but also because they provide information for other readers curious about the Dark Continent. David Livingstone’s first book about Africa would not be published until a year after Wilson’s.

One item of scientific importance Wilson talks about in Western Africa, 366-67, concerns his discovery of some skulls. He says—

“But the most formidable of all animals in the woods of Africa is the famous, but recently discovered, Troglodytes Gorilla, called, in the language of the Gaboon, Njena. The writer was the first to call the attention of naturalists to this animal. Toward the close of 1846 he accidentally came across the skull of one, which he knew at once, from its peculiar shape and outline, to belong to an undescribed species. After some searching a second skull was procured, but of smaller size. No other portion of the skeleton could be procured for some time afterward. The natives, however, seemed to be perfectly familiar with the habits and character of the animal, gave minute accounts of its size, its ferocity, and the kind of woods which it frequented; they also gave confident assurances that in due time a perfect skeleton should be produced. In the meantime, impressions were taken in this country where the two heads were procured, and all the information that could be obtained from the natives was published, and served to awaken the liveliest interest among naturalists. Since then perfect skeletons have been taken to England and France, and brought to this country, so that scientific men have sufficient knowledge of the subject to assign this animal its proper place in natural history. It belongs to the orang-outang, or chimpanzee family, but is larger and much more powerful than any other known species. The writer has seen one of these animals after it was killed. It is almost impossible to give a correct idea, either of the hideousness of its looks, or the amazing muscular power which it possesses. Its intensely black face not only reveals features greatly exaggerated, but the whole countenance is but one expression of savage ferocity. Large eyeballs, a crest of long hair, which falls over the forehead when it is angry, a mouth of immense capacity, revealing a set of terrible teeth, and large protruding ears, altogether make it one of the most frightful animals in the world. It is not surprising that the natives are afraid to encounter them even when armed. The skeleton of one, presented by the writer to the Natural History Society of Boston, is supposed to be five feet and a half high, and with its flesh, thick skin, and the long, shaggy hair with which it is covered, it must have been nearly four feet across the shoulders. The natives say it is ferocious, and invariably gives battle whenever it meets a single person. I have seen a man the calf of whose leg was nearly torn off in an encounter with one of these monsters, and he would probably have been torn to pieces in a very short time if his companions had not come to his rescue. It is said they will wrest a musket from the hands of a man and crush the barrel between their jaws, and there is nothing, judging from the muscles of the jaws, or the size of their teeth, that renders such a thing improbable” (pp. 177-78)

Wilson’s quote does not mention that he received help with the skulls from Dr. Thomas Savage of the Episcopal Mission in Cape Palmas. When Wilson left Cape Palmas to establish a mission station in the Gaboon region the Cape Palmas campus and its personnel were turned over to the Episcopal Mission. Erskine Clarke provides some details about transporting the skulls noting that when Wilson and Savage travelled with their wives to the States in 1846 they made port in New York, where Wilson remained after loaning “to Dr. Thomas Savage” the skulls to take to Boston for examination by scholars. However, Clarke adds, when Savage finished with the bones they were left with the Natural History Society. It had been Wilson’s desire that Savage return the bones for display at the ABCFM facility in New York. It could be Wilson did not mention Savage in the Western Africa quote because he was angry with him about not returning the bones (By the Rivers, p. 281). More light is shed on the story by the article “The Missionary and the Gorilla” by Richard Conniff in Yale Alumni Magazine, Sep-Oct 2008, which includes a photograph of the two skulls; the larger one is from a male gorilla and the smaller is that of a female. Conniff says Savage joined Harvard professor Jeffries Wyman presenting a paper before the Boston Society of Natural History, August 1847. The highly detailed and illustrated paper was published in the Boston Journal of Natural History, Dec. 1847, bearing the title, “Notice of the External Characters and Habits of Troglodytes Gorilla, A New Species of Orang from the Gaboon River” (417ff). Savage did not take all the credit for the discovery even though Wilson was in far-away Africa but instead gave Wilson credit as a colleague discovering and studying the skulls, but it seems Wilson never saw the Boston Journal article. It may well be that communication between the two men was confused about the eventual home for the skulls. Wilson’s wish to keep the skulls at the ABCFM facility shows that even though his find was significant, he thought it more important for the work of the mission that personnel see them. Over the years the skulls were moved among institutions but at the time of Conniff’s article they were in the collection of Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. The “five feet and a half high” gorilla specimen Wilson mentioned in Western Africa was located after the skulls.

Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of the Species, would not be published until 1859, but soon after release it was the subject of debate. As evolution theory developed it was concerned with the origin of man theorizing he developed from apes over an extended period of time. One individual important for spreading the theory was the academic nicknamed “Darwin’s bulldog,” Thomas H. Huxley (1825-1895). Darwin tended to reclusiveness and depression while Huxley was a tenacious and aggressive proponent of ideas. Just a year after Origin was released, Huxley debated Bishop Samuel Wilberforce concerning evolution with Huxley presenting the case for evolution while Wilberforce defended the Bible’s record of man’s creation in the image of God. By 1863, Huxley knew of Wilson’s gorilla discovery mentioning him in “On the Natural History of the Man-Like Apes” (Collected Essays, vol. 7, London, 1894, p. 31). Huxley said—

“In 1847, Dr. Savage had the good fortune to make another and most important addition to our knowledge of the man-like Apes; for, being unexpectedly detained at the Gaboon River, he saw in the house of the Rev. Mr. Wilson, a missionary resident there, a skull represented by the natives to be a monkey-like animal, remarkable for its size, ferocity, and habits. ‘From the contour of the skull, and the information derived from several intelligent natives, I was induced,’ says Dr. Savage (using the term Orang in its old general sense) ‘to believe that it belonged to a new species of Orang. I expressed this opinion to Mr. Wilson, with a desire for further investigation; and, if possible, to decide the point by the inspection of a specimen alive or dead.’ The result of the combined exertions of Messrs. Savage and Wilson was not only the obtaining of a very full account of the habits of this new creature, but a still more important service to science, enabling the excellent American anatomist already mentioned, Professor Wyman, to describe, from ample materials, the distinctive osteological characters of the new form. This animal was called by the natives of the Gaboon Enge-ena, a name obviously identical with the Ingena of Bowdich [sic]; and Dr. Savage arrived at the conviction that this last discovered of all the great Apes was the long-sought Pongo of Battell.”

Both Nathaniel Bowditch (1773-1838) and Battell (died 1614) had sighted what were likely gorillas, but it appears that Wilson’s skulls were the first tangible evidence for direct scholarly assessment. Huxley referred to Wilson’s skull discovery in making his case for the evolution of man from ape ancestors. Given how much debate there has been about man’s origin, it is ironic that Wilson made the gorilla discovery in that the skulls became evidence for man evolving. Added to this is his wife, Jane Bayard, was a cousin of Charles Hodge who said in What is Darwinism?, 1874, that Darwin’s theory was “the most thoroughly naturalistic that can be imagined” and necessarily atheistic (p. 85). As the years passed following Wilson’s find, what thoughts did he have about the place of his scientific contribution to the development of evolution.

In Memoirs of Rev. John Leighton Wilson, D.D., Alice Johnson, care giver for Wilson after his wife’s death, commented, “During the last year of his life his eye-sight became very poor, and with exception of reading the Bible in the morning, that being good type, he was unable to use his eyes during the day, and I often, during the heated discussions that were going on at that time about evolution, read to him several hours a day.” The heated discussions revolved around the case of James Woodrow and his teaching about evolution. Woodrow expressed his ideas in the article, “Evolution,” in the Southern Presbyterian Review, July 1884. Woodrow did not say man was descended from apes straightaway, but he did allow for progression or change in vertebrates and their organs, while man with his skeleton similar to vertebrates has the added factor of the imago Dei (p. 367). With regard to adaptation or changes in animals over time, he called the changes new creation. Woodrow’s teaching on evolution is not clearly presented in either the SPR article or in his defense before the Synod of South Carolina published in SPR 36, January 1885, but he allows for development of man’s physical form over time and an extended era preceding God’s creation in the book of Genesis. J. Leighton Wilson’s interest in the Woodrow case was not mere curiosity about a theological debate, but added to the theological concerns was the relationship between Wilson and Woodrow. Woodrow may have been Wilson’s closest Columbia Seminary community friend. Woodrow preached Wilson’s funeral, then just before the casket was sealed, he kissed his forehead (Memoirs, 319). A truly admirable man named J. Leighton Wilson, D.D., passed away July 13, 1886, the same year James Woodrow was removed from the faculty of Columbia Theological Seminary by the Synod of South Carolina of the PCUS. One can only wonder about what was said over the years after his find when he and James Woodrow sat down in the parlor and had a chat, however, there is no indication that Wilson held to his friend’s views regarding evolution, apes, and the origin of man.

Barry Waugh

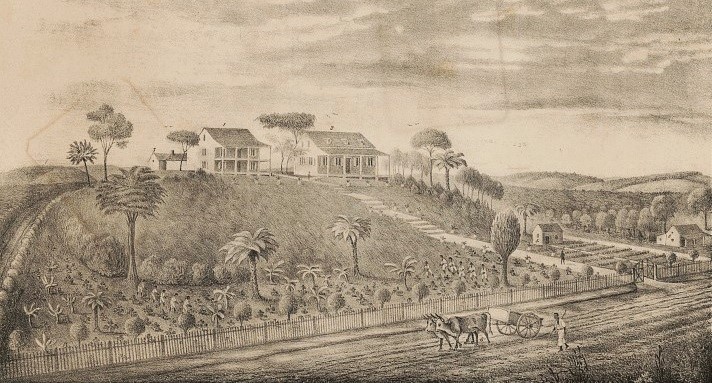

Notes—The header is snipped from “Episcopal Mission Cape Palmas West Africa, 1838,” as from the Library of Congress Digital Collection; the header shows the mission compound for Wilson’s work and the building in the foreground on the hill is likely the Wilson home. The portrait is from Alfred Nevin’s, Encyclopædia of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, Philadelphia, 1884. The complete information about Wilson’s biography is—Hampden C. DuBose, Memoirs of Rev. John Leighton Wilson, D.D., Missionary to Africa and Secretary of Foreign Missions, Richmond: Presbyterian Committee of Publication, 1895. Erskine Clarke, By the Rivers of Water: A Nineteenth Century Atlantic Odyssey, New York: Basic Books, 2013, this book provides a narrative of the Wilsons years of work in Africa that ended with their return to South Carolina before the Civil War after nineteen years of ministry. Two brief biographies of Wilson accessed for this post are—H. A. White, Southern Presbyterian Leaders 1683-1911, reprinted by Banner of Truth, 2000; and John Miller Wells, Southern Presbyterian Worthies, Richmond: Presbyterian Committee of Publication, 1936. For information on the Woodrow case see, David B. Calhoun, Our Southern Zion: Old Columbia Seminary (1828-1927), Carlisle: Banner of Truth, 2012, pp. 265-80; and C. N. Willborn, “Another Lost Cause” in John L. Girardeau: Pastor of Slaves and Theologian of Causes, A Historical Account of the Life and Contributions of an Often Neglected Southern Presbyterian Minister and Theologian, PhD dissertation, Westminster Theological Seminary, 2003, pp. 245-77. The evolution publications regarding the Woodrow case are readily available in PDF on the Log College Press website at, “James Woodrow (1828-1907).” Also on the LCP site are the Southern Presbyterian Review and a list of Wilson’s books with some available for download, see “John Leighton Wilson (1809-1886).”