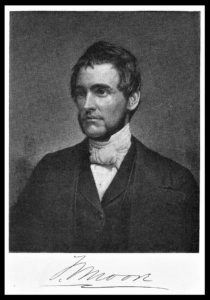

Thomas Verner Moore might be known to readers thanks to the reprints of his two major books by Banner of Truth—The Last Days of Jesus and his commentary on Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi.[1] Other publications issued by him over the years include more than fifty sermons, articles, book reviews, lectures, poems, hymns, and a monograph titled The Culdee Church. He was also a dedicated pastor and churchman respected by fellow elders as exemplified in his receiving the second most votes for the Chair of Pastoral Theology and Rhetoric in Allegheny Seminary at the Old School General Assembly in 1853, and then in 1867 he was elected moderator of the Presbyterian Church in the United States (P.C.U.S.) General Assembly.[2] In addition to Moore’s pastoral ministry in Richmond he owned and operated the Central Presbyterian newspaper with the pastor of Second Church, Moses D. Hoge, and he was for several years chairman of the Richmond Ministerial Association. In 1850, he turned down the presidency of Lafayette College in his home state of Pennsylvania. Moore was known, respected, and honored in his own era, and if he had not suffered an extended period of declining health leading to death at the age of fifty-three, he would have left a greater legacy of ministry and service to Christ.

Thomas Verner Moore might be known to readers thanks to the reprints of his two major books by Banner of Truth—The Last Days of Jesus and his commentary on Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi.[1] Other publications issued by him over the years include more than fifty sermons, articles, book reviews, lectures, poems, hymns, and a monograph titled The Culdee Church. He was also a dedicated pastor and churchman respected by fellow elders as exemplified in his receiving the second most votes for the Chair of Pastoral Theology and Rhetoric in Allegheny Seminary at the Old School General Assembly in 1853, and then in 1867 he was elected moderator of the Presbyterian Church in the United States (P.C.U.S.) General Assembly.[2] In addition to Moore’s pastoral ministry in Richmond he owned and operated the Central Presbyterian newspaper with the pastor of Second Church, Moses D. Hoge, and he was for several years chairman of the Richmond Ministerial Association. In 1850, he turned down the presidency of Lafayette College in his home state of Pennsylvania. Moore was known, respected, and honored in his own era, and if he had not suffered an extended period of declining health leading to death at the age of fifty-three, he would have left a greater legacy of ministry and service to Christ.

It is the purpose of this post to provide some biographical information about T. V. Moore and through examination of his second place contribution to Prize Essays on Juvenile Delinquency, 1855, understand more about his ideas. Comparison of his essay to those by the other two recipients of prizes will provide Moore’s view within its historical and intellectual context.

Moore’s Early Years

Thomas Verner Moore was born February 1, 1818 in Newville, Pennsylvania.[3] His father John was an immigrant from Ireland who owned and operated a local water powered mill; his mother Rachel McCullough served her family as a homemaker. His early education was provided by a Presbyterian minister, likely his pastor. Formal education for Moore began at Hanover College, Indiana. However, he stayed only a year but it was long enough to become acquainted with the woman he would marry in 1842, Sarah Blythe, the daughter of the first president of Hanover, James Blythe.[4] Moore transferred to Dickinson College in Carlisle to complete college studies while enjoying eased access to the family home in nearby Newville. Graduated from Dickinson, Moore headed east to receive his divinity education at Princeton Theological Seminary, where he was instructed by Samuel Miller, Archibald Alexander, and Charles Hodge. For a brief time after seminary, he was an agent with the American Colonization Society in Pennsylvania.[5]

Moore’s disenchantment with colonization work combined with a renewed sense of calling to pastoral ministry contributed to his accepting a call from Second Presbyterian Church, Carlisle. After a difficult four-year ministry in which schism discouraged him, Moore sought to demit the ministry but because of encouragement from presbytery he left Carlisle to serve the Greencastle Church within Carlisle Presbytery. After just a matter of months, Moore was invited to candidate for the pulpit of First Church, Richmond, Virginia, to follow William S. Plumer who transferred to the Franklin Street Church of Baltimore Maryland.[6] The pastoral search committee at First Church was having a difficult time locating a candidate as indicated by the rejections from both Stuart Robinson and B. M. Smith.[7] Moore accepted the call and moved to Richmond. The move was beneficial because it put behind him the difficulties faced in Carlisle Presbytery that had caused doubt about his ministerial call. The relocation would also, he hoped, provide an environment better suited to his strong sense of republican government, because he believed the best government was local, limited, and begins with the individual responsible to God that seeks the common good in the nation, church, and home.

After some adjusting for differences living in the South, Sarah and Thomas increasingly appreciated their new home, their friends, and the milder weather. The transplanted Pennsylvanians were enjoying a prospering ministry and a quiver filling with children (Psalm 127:5), but the birth of their third son and fourth child, Francis (Frank), led to tragedy because complications claimed Sarah’s life shortly after the baby’s delivery in March 1849. Within a few years of Sarah’s death, First Church’s congregation with more than twice as many women as men provided Moore with another wife, Matilda Gwathmey, the daughter of a church elder.[8] Thomas and Matilda were married by Dr. Plumer, May 20, 1852, while they were visiting Charleston, South Carolina, for the Old School General Assembly that met in the Glebe Street Church. Moore and Matilda would go on to have two children, T. Vernor Moore, and a daughter possibly named Fanny.

After some adjusting for differences living in the South, Sarah and Thomas increasingly appreciated their new home, their friends, and the milder weather. The transplanted Pennsylvanians were enjoying a prospering ministry and a quiver filling with children (Psalm 127:5), but the birth of their third son and fourth child, Francis (Frank), led to tragedy because complications claimed Sarah’s life shortly after the baby’s delivery in March 1849. Within a few years of Sarah’s death, First Church’s congregation with more than twice as many women as men provided Moore with another wife, Matilda Gwathmey, the daughter of a church elder.[8] Thomas and Matilda were married by Dr. Plumer, May 20, 1852, while they were visiting Charleston, South Carolina, for the Old School General Assembly that met in the Glebe Street Church. Moore and Matilda would go on to have two children, T. Vernor Moore, and a daughter possibly named Fanny.

New Challenge in Writing for T. V. Moore

Moore wrote often during his first years of ministry but the number of publications was limited by his primary commitment to pastor First Church. He composed articles and reviews about Presbyterian government, the inspiration of the Bible, evolution, and Thomas Chalmers as well as other theological and historical personalities. His writing had been standard fare for educated ministers of the day, but then he decided to enter an essay competition that would present his views in the context of the recently developed field of sociology by writing about juvenile delinquency. The term sociology was coined by the field’s chief proponent and theoretician, Auguste Comte (1798-1857). Sociology was emerging to address problems created by the Industrial Revolution such as urbanization, unemployment, crime, poverty, abandoned children, and vagrancy. The United States experienced delinquency problems similar to those in England as presented in Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist which tells the story of an orphaned boy and his colleagues being schooled in pickpocketing by their corrupt master named Fagan. As struggling families shifted from farming and rural life to industrialized cities parents sometimes abandoned their children leaving them to the streets or to the care of orphanages. Moore saw that social, psychological, economic, and domestic factors contributed to the increase of juvenile delinquency, so he took up his pen as a pastor concerned for the family to compose an essay for the contest sponsored by the House of Refuge in Philadelphia. The House of Refuge published the winners in Prize Essays on Juvenile Delinquency Published Under the Direction of the Board of Managers of the House of Refuge, Philadelphia, Philadelphia: Edward C. & John Biddle, 1855.[9] The three winning entries by Edward Everett Hale, T. V. Moore, and Arthur Harper Grimshaw had been selected from forty-four submissions. Hale received 100.00 for first prize and Moore and Grimshaw were each given 50.00.[10]

Edward Everett Hale Essay

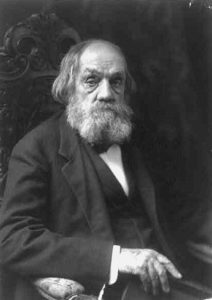

Bearing the ancestral pedigree of revolutionary New England, Edward Everett Hale was born in Boston, April 3, 1822, the son of Nathan Hale (1784-1853), the nephew of the statesman and orator Edward Everett. He was also the grand nephew of Nathan Hale (1755-1776) renown for his patriotism as he died for independence regretting that he had but one life to give for his country. E. E. Hale’s education was of the highest order with the best schools and tutors including graduation from Harvard in 1839. He became a minister of the Church of Unity, Worcester, Massachusetts, 1846-1856, and then the South Congregational (Unitarian) Church, Boston, 1856-1899. He was against slavery and found particular joy in expressing his opinions regarding the bill that became the Kansas Nebraska Act in 1854; his enthusiasm induced him to publish a history of the Act. He was a speaker for the common man and worked to improve their home life. Hale was a voluminous writer with a compelling manner and dynamic personality that contributed to his great popularity, but if he is recognized today it is likely because he wrote the Atlantic Monthly article, “The Man Without a Country,” 1863. As if to give a life-time achievement award, Hale was appointed Chaplain of the United States Senate at the age of 81. He died in Roxbury, June 10, 1909, after overseeing the publication of his writings in ten volumes. E. E. Hale’s interest in the plight of the working man, concern for the problems of industrial urban living, and social views contributed to his interest in writing about the problem of juvenile delinquency.[11]

Bearing the ancestral pedigree of revolutionary New England, Edward Everett Hale was born in Boston, April 3, 1822, the son of Nathan Hale (1784-1853), the nephew of the statesman and orator Edward Everett. He was also the grand nephew of Nathan Hale (1755-1776) renown for his patriotism as he died for independence regretting that he had but one life to give for his country. E. E. Hale’s education was of the highest order with the best schools and tutors including graduation from Harvard in 1839. He became a minister of the Church of Unity, Worcester, Massachusetts, 1846-1856, and then the South Congregational (Unitarian) Church, Boston, 1856-1899. He was against slavery and found particular joy in expressing his opinions regarding the bill that became the Kansas Nebraska Act in 1854; his enthusiasm induced him to publish a history of the Act. He was a speaker for the common man and worked to improve their home life. Hale was a voluminous writer with a compelling manner and dynamic personality that contributed to his great popularity, but if he is recognized today it is likely because he wrote the Atlantic Monthly article, “The Man Without a Country,” 1863. As if to give a life-time achievement award, Hale was appointed Chaplain of the United States Senate at the age of 81. He died in Roxbury, June 10, 1909, after overseeing the publication of his writings in ten volumes. E. E. Hale’s interest in the plight of the working man, concern for the problems of industrial urban living, and social views contributed to his interest in writing about the problem of juvenile delinquency.[11]

“The State’s Care of its Children: Considered as a Check on Juvenile Delinquency,” (11-44)

Hale deals with juvenile delinquency primarily from the perspective of the government’s responsibility to meet the challenge. Hale thought the industrial revolution contributed to the delinquency problem because machinery used in manufacturing allowed young people to quickly acquire a singular skill operating a piece of specialized equipment. He thought it better that youths be apprenticed in a trade, for example a joiner, to learn how to work wood with traditional hand tools than to work in a factory preparing lumber for joining with a steam-driven planer.[12] Hale was reluctant to give up the old ways believing each young man having a trade was better than working in a factory. He thought a young man trained as a factory worker was simply “training him to be ‘a vagabond’” (14).

At the time these essays were written juveniles that committed crimes were generally imprisoned with adult offenders that passed on their criminal knowledge to the young people. Hale believed that putting the juvenile in prison established a pattern for life—once a young man is initiated into prison life, he is less likely to fear another term incarcerated and he would be tutored by criminals to become better thieves (17-19). He was also concerned that prison denied juveniles exercise and fresh air needed for good health. For Hale, putting juvenile delinquents in prison was at best the last resort and at worst condemnation to a life of crime and the stigma of having been in prison.

In America, said Hale, the family is the most important influence for three aspects of a child’s maturation—moral, religious, and vocational. He commented that, “The [American] system is founded on a judicious regard for the rights of families, and for the natural affection of parents for their children” (22). From what he said it might be expected that he would defend the family, but instead he said

It is all the while very evident, that in many instances, the State is a great sufferer, by leaving children for these three most important fields of discipline [i.e., moral, religious, and vocational], to persons wholly incompetent. It is more agreeable to a father and a mother, to have their children left to their own care; but when they bring them up fit for nothing—intemperate, irreligious, or vagabonds—the State sustains a great loss from that consideration, which has treated so delicately the parents’ rights. The child sustains a like loss (22).

Hale expresses concern regarding how much it is going to cost the state to care for these incompetently raised juveniles (22-23). He continued his essay observing that “wherever there are parents, incompetent to make their homes fit training places for their children, the State should be glad, should be eager to undertake their care” (25). This comment night be surprising in the currently context given the size and reach of government, but in Moore’s era it must have induced concern about the potential power of the government over the family.

Hale related his own experience concerning a widow woman whose son was “disobedient” and “truant” (24). He compared her desire to get the boy into the Massachusetts Reform School to those parents in other walks of life who struggled to gain appointments for their sons to West Point (25). The mother resorted to what she believed was her only choice—a government operated reform school. The “State,” says Hale, should rejoice that “incompetent” parents surrender their children “to its disposal” (26). However, it is important that two aspects concerning juvenile care must be remembered—first, the care rendered must be economical and as far as possible self-funding, and secondly, the training should be well done and produce capable and virtuous men and women (26). Incompetent parents surrender their children to a fiscally efficient state that creates productive, skilled, and virtuous citizens.

Hale proposed a system of juvenile delinquent care that differed from the Massachusetts Reform School. He thought a “large Receiving school supplying various separate homes” could be the basis with the homes managed by a government board (35). Dormitory type facilities, said Hale, were detrimental to juveniles because they need to be under the care of a “Christian man and a Christian woman,” instead of a superintendent, teachers, chaplains, and trustees found in dormitory settings (37). The children were to be distributed to private homes for care and when old enough they needed to become trade apprentices. Any funds earned by the apprentices should be used to defray their cost to the house masters and recover the debts incurred by the government program (27-28). A home situation is better for juvenile care because dormitory living teaches the youth to despise the family and leads to a selfish me-first attitude (38).

For Edward Everett Hale, the government was the key to dealing with the problem of juvenile delinquency because it could shoulder the burden of caring for youths from incompetently parented homes. He believed that because home life is better than dormitory life to keep young people from having a delinquent lifestyle, Christian parents should be overseeing the youths under the eye of a government board. The home should be Christian in the sense of teaching morality and industry so the youths become productive members of society. Most importantly, the delinquent’s vocational education should provide income to defray the costs incurred by the household providing care and to defray government administration costs. The state is very important for Hale’s program and his spelling with an upper case S may be more than a convention of the day.

Arthur Harper Grimshaw Essay

In 1824, Arthur Harper Grimshaw was born in Pennsylvania where he graduated from the University of Pennsylvania Medical School in 1845. Initially practicing medicine in Pennsylvania, he moved his office to Wilmington, Delaware in 1849. The next year he married Ann Elizabeth Bailey. At the time of the essay competition Grimshaw was not only a physician but also a lecturer in the Hannah More Academy for Young Ladies founded by his sisters, Charlotte and Isabella. He would die May 17, 1891 of what was called “congestion of the brain.” Grimshaw’s background as a physician and his concern for children would have contributed to his interest in the problem of juvenile delinquency.

In 1824, Arthur Harper Grimshaw was born in Pennsylvania where he graduated from the University of Pennsylvania Medical School in 1845. Initially practicing medicine in Pennsylvania, he moved his office to Wilmington, Delaware in 1849. The next year he married Ann Elizabeth Bailey. At the time of the essay competition Grimshaw was not only a physician but also a lecturer in the Hannah More Academy for Young Ladies founded by his sisters, Charlotte and Isabella. He would die May 17, 1891 of what was called “congestion of the brain.” Grimshaw’s background as a physician and his concern for children would have contributed to his interest in the problem of juvenile delinquency.

“An Essay on Juvenile Delinquency,” (91-159)

By far the longest of the essays, Grimshaw begins stating that laws, prison, and incarceration do not improve society but instead achieve only the separation of the unlawful from the public. For juvenile delinquency to be eliminated, the “causes that lead to commission of crimes” must be removed, and it was his plan for his essay to present the causes of delinquency and suggest remedies (93-4). His remedies would “require time, steady perseverance, and an unfaltering faith in their power, in order to produce the desired effect” (95).

Grimshaw lists eight causes of juvenile delinquency with each one explained in a section of the essay. Causes include—lack of education, social and architectural location of the person’s residence, public charities, lack of instruction in morality and a positive parental example, the system of apprenticing used by employers, lack of religious instruction, parents lacking religious improvement, and children becoming orphaned during their early years. Grimshaw expanded on each of these causes, but just a selection from the eight will be considered here.

The cause of social and architectural location refers to the living conditions of the impoverished who often dwelt in poorly ventilated, crowded, and unsanitary conditions (109-19). This cause would continue to be present and lead to public outrage when in 1890 Danish immigrant Jacob Riis published How the Other Half Lives, which showed how primarily southern European immigrants were living in unhealthy and unsafe tenements in New York. In Grimshaw’s day immigrants came primarily from northern European countries such as Great Britain, Scandinavia, the Netherlands, and Germany (China in the West), but they too faced overcrowding in the East with many deciding to move to the frontier for better opportunities. One American Presbyterian seminary professor, B. B. Warfield, was sufficiently affected by Riis’s book to write a review in The Presbyterian and Reformed Review. Grimshaw contended that improved living conditions would provide better opportunities for immigrants and their children yielding a reduction in juvenile delinquency.

A second cause of delinquency for Grimshaw was public charities intended to alleviate poverty. A charity for him is an organization that provides financial and/or vocational direction for those in need. Before Grimshaw, Alexis de Tocqueville published An Essay on Pauperism, 1835, expressing his opinion that charity, whether public or private, created a dependent class that had no reason to labor to improve their estate in life.[13] According to Gertrude Himmelfarb, de Tocqueville composed Pauperism immediately after completion of volume one of his well-known Democracy in America, but the work on pauperism focused attention on Western Europe. However, the principle of Pauperism, as was discovered by American political conservatives at the end of the twentieth century, could also be applied to the United States. Public charity in Grimshaw’s era was more developed in England and other European countries than in America. E. E. Hale also saw the problem of charity because he thought private financial gifts to the urban poor was “mistaken almsgiving” because it could result in removing the incentive for work (13ff). Grimshaw commented with a distinctively de Tocqueville twist that “the more we multiply ‘charities,’ the more we increase poverty” (119). He added that society should “cut off poverty by drying up the sources; in a word, prevent misery instead of making vain attempts to relieve it” (120). The irony of this perspective adopted by both Hale and Grimshaw is that considering their view that government should shoulder the burden of solving the juvenile delinquency problem through public institutions and services, why did they not develop their solution to the problem of delinquent youth with greater emphasis on the duties of parents and the responsibilities of the juveniles themselves? Both affirmed the importance of a family environment, both mentioned the importance of some sort of Christianity, but then both looked to government for resolution. If de Tocqueville was correct with his thesis, could it also be that public care of juvenile delinquents produces a class dependent on public care for all of its problems just as surely as public charity creates an economically dependent class.

Grimshaw took the opposite position to E. E. Hale’s perspective on apprenticing as a solution to the delinquency problem. The reason for the difference is that Grimshaw had a different definition of apprentice in mind. He believed that apprenticing was herding boys into manufacturing facilities where they did simple and unskilled tasks with machinery; Hale saw apprenticing as training the youth in a skilled and necessary trade that would always provide income. Hale’s view was consistent with vocational training dating to antiquity because youths were taught skills by masters of those skills, but labor was affected by the Industrial Revolution so it became necessary to consider Grimshaw’s idea that apprenticeship should not only involve Hale’s concern for apprenticeships in local shop skills—tailor, jeweler, carpenter, etc.—but also manufactory training.

Grimshaw’s sixth and seventh points are regarding religious instruction by parents teaching their children religion while they themselves received religious instruction through learning to read in adult Sunday school programs (139-40; 144). At this point in time, Sunday school was used to teach people how to read with instructors using the Bible and doctrinal catechisms for the textbooks to teach the Gospel and provide moral instruction. Grimshaw looked to Thomas Chalmers as an example of appropriate use of Sunday schools saying that he taught “a high point of command over the moral destinies of our cities, for the susceptibilities of childhood and of youth are what they have to deal with” (144).[14] Granted that Sunday schools taught morality, but it was morality developed from the Gospel’s work of sanctification as one grows in grace through the transforming work of Christ—Sunday schools did not teach morality alone.

Both Grimshaw and Hale saw the solution to the delinquency problem as predominantly founded in society and government, except for their concern to teach morality in some vague Christian sense. Notice here that Christianity was seen by the general public as a religion of does and don’ts in the era and it is often seen that way today, however, the does and don’ts for Christians flow from grateful obedience for what the Father has done through Christ’s work of grace. Just as ideally a child obeys a parent out of love, so the Christian obeys God out of love for His great love. For Grimshaw the religious aspect to resolving the juvenile delinquency problem is teaching the Bible’s morality. Both Hale and Grimshaw express the importance of families, including surrogate families, to teach youth and keep them from delinquency, but their emphases show that existing cases of delinquency must be resolved primarily by the government.

Moore’s Essay, “God’s University,” (45-89)[15]

Moore’s essay opens showing the primary source of his solution to the juvenile delinquency problem. The essay is prefaced with a page of Bible passages as follows: Ps. 68:6; Gn. 18:19; 1 Sm. 3:13; Pr. 13:24, 19:18, 22:15, 23:13, 14, 29:15; Heb. 12:9; Ep. 6:4; Pr. 22:6; 1 Ch. 13:14, 16:16, 43. He then presents his purpose:

Moore’s essay opens showing the primary source of his solution to the juvenile delinquency problem. The essay is prefaced with a page of Bible passages as follows: Ps. 68:6; Gn. 18:19; 1 Sm. 3:13; Pr. 13:24, 19:18, 22:15, 23:13, 14, 29:15; Heb. 12:9; Ep. 6:4; Pr. 22:6; 1 Ch. 13:14, 16:16, 43. He then presents his purpose:

Believing it [the family] to be the divinely appointed institute for the training of the young, and the neglect of its agencies to be the ground cause of juvenile delinquency at the present time, and the proper use of its discipline, instruction, and worship to be the desired remedy, we propose to consider this great educational institute, which, as the only one that God has made universal on the earth, we have ventured the term “God’s University,” of the divinely appointed means for educating the human race for time and eternity, in all these particulars, no specifically assigned to the Church (49-50).

Moore continues by setting forth the plan for presenting his subject by looking

at its general design, and then consider it under the aspects of a government, a school, and a church; defining its province, explain its duties and pointing out some errors, prevalent in these several departments of its action (50).

A section of the essay is dedicated to each of the four main points about the family—first, the design of the family; second, the family as a government; third, the family as a school; and fourth, the family as a church. The longest section is the family as a government with fifteen pages of text.

(1) The Design of the Family

Moore says the family is the fundamental unit of society, and families, God’s universities, must flourish for a nation’s stability—without strong families, society suffers (50). His comment was not only applicable to his universe but its truth finds merit for the contemporary scene inasmuch as he wrote, “Let a skeptical and socialistic philosophy succeed in weakening, or dissolving the bonds of the family institute, and the very physical constitution of the race must degenerate” (51). The home has a great responsibility to care for the child not only in the short term, but the long term. Supervising and training children while they are home not only benefits them immediately but also for the rest of their lives. A proper home prepares the child for life (51). Most importantly, the home prepares children for the greater issue of eternity, or as Moore puts it, the family’s “scope is not arrested at old age, but stretches on to another life, and finds its last and highest design in training the soul for heaven” (53). The world is a hostile place for the young, so parental concerns for eternity were ever present. As Moore expressed it, the family is to “fit those who have lived and loved on earth, to live and love in heaven” (54).

(2) The Family as a Government

Moore began this section commenting that the oldest form of government on earth is the family. The Fifth Commandment has established the rule of the household instructing children to honor their parents in conjunction with God’s instruction through the Apostle Paul, “the husband is head of the wife as Christ is the head of the church” (Eph. 5:23)(55). All members of the home are to obey God with mutual concern for the welfare of the family just as any citizen obeys God with concern for the common good (55).

For the family to be well governed, says Moore, there should be household rules. These rules should be established by the parents in private so the children do not see the mother and father in disagreement as they work out household legislation. There should not be too much legislation—too many rules exasperate children—nor should there be so few that it leads to confusion (56-57). As the rules are applied it should be done with equity, love, and understanding of the sensitivities of the particular child; one child may think a punishment more than can be borne, but another youngster receives the same punishment recognizing it is fair and just (57-59). Both parents must be consistent in discipline or the child will quickly learn how to divide and conquer through setting parent against parent (57-39). Very important for a properly governed home is teaching the young to do what is right simply because it is right; cajoling children with enticements, money, and prizes should not be done (59).

Having presented an outline of the importance of good family government, Moore then comments, as Hale and Grimshaw did to a lesser degree, that juvenile delinquency is a result of poor family government. Acknowledging that poverty, abuse, and criminal environments in some homes contribute to juvenile delinquency, Moore then observed that rebellious children also come from prosperous families and Christian homes. Delinquency may result because parents simply do not care to discipline properly, and they bear responsibility for their negligence (59-60). Among the duties of caring parents are doing their best to keep their children from corrupting external influences. Moore mentioned the places where youth might be tempted in his day included—saloons, engine houses (firehouses), billiard halls, bowling alleys, and circuses (60). These were places that provided temptations for young people in the era, to which Moore commented, “can it be wondered at, that, if boys are allowed to spend their evenings and their Sabbaths away from home, and beyond parental oversight, they could be corrupted” (60-61). Moore’s era had temptation environments that may no longer be problematic today, but modern technology provides temptations that could not have been imagined then.

Poor family government can be traced to several shortcomings on the part of parents. A mother or father sometimes postpones beginning child discipline until it is too late. Some, says Moore, believed that a child should not be restrained until old enough to be reasoned with (65). On the other hand, he warned that parents can be too severe in their application of discipline, so the correction needs to be fitted to the offence in a fair and equitable manner. Using an apt illustration with a branch and its twigs, Moore commented that some disobedience is indicative of a deeper or more fundamental problem, so get to the “branch” of the problem and the “twigs” will also be corrected. Do not allow a child to do today what might be prohibited tomorrow, and be consistent without vacillation or caprice (66). Finally, allowing children to do as they please provides no direction because what they want to do may include sin (68-69).

He summed up his teaching on family government by saying “to fail in family government then, is to be an accessory to a breach of the fifth commandment…if then juvenile depravity is to be thoroughly corrected, we must begin…by restoring family government” (69).

(3) The Family as a School

Having written nearly half of his essay on the family as a government, Moore turns to the family as a school for the next factor needed to resolve the problem of delinquency. In Moore’s era, much of the educational process was done in the home or privately arranged by the parents with tutors or educational contractors. Public education was on the rise but home governed training was still common. He commented regarding the family as a school that the “oldest seminary on earth is the family fireside” (69). He added that

the family is a school, and education is taking place, whether we recognize it or not.…We may neglect our part, but education will go on, and other teachers will take our place, and carry out the work, for evil, if we do not for good.…if we plant not the seeds of the right and true, they will plant those of bitterness, sadness and sorrow, the harvest of which is sin and perdition. Hence we can never arrest the education of a child, we can only direct it, and see that it is what it should be (71).

Not only is the home the fundamental institution of society but also the basic institution for education. Parents answer the whys, whats, and whos of toddlers long before they take a seat in a school desk. Children will learn but the key question is who are they going to learn from and what will be the teacher’s perspective?

Children, said Moore, are to be brought up “in the nurture and admonition of the Lord” (Eph. 6:4)(74). Christian education should use catechisms and the best formulations of truth so that children are trained to be Christians (75). The covenant home has no strangers within its walls but lads and lasses baptized and blessed by parents training them to grow up and be communicant members of Christ’s church. Even though the general public may see Christianity as a means of moral good built on dos and don’ts, Moore shows that the moral good flows from training children to be Christians—from his perspective the Covenant of Grace calls parents to train up children in the way they should go (Pro. 22:6). The use of catechetical questioning presents opportunities for children to respond with inquiries of concern; questions provide the opportunity for instruction because curiosity is the beginning of learning (74). Moore added that

Christian nurture is such instruction in the great truths and duties of our holy religion as shall give a knowledge of them as full and accurate as the nature of the child will allow; and Christian admonition is such authoritative enforcement of these duties, and application of these truths in daily life, as shall bring them into vital contact with the soul, by the promised blessing of God. Christian education is educating children to be Christians, and nothing short of this will fill up this great conception (74).

He went on to warn parents

If we do not educate them to the religion of God, others will to the service of Satan, and when we come at last with our seed we will find the ground pre-occupied, and the education already completed (77).

Training children in the nurture and admonition of the Lord is the responsibility of those whose children they are—the parents in conjunction with their churches. The fundamental unit of society and the fundamental government of any nation is the family. The hearts and minds of children are fallow ground for the reception of whatever seeds of knowledge are sown. The choice is to cultivate the youngsters from the seed of the revealed will of God, the Bible, or have their lives corrupted with the weeds distributed by those having different agendas.

Moore made a forced transition in subject matter as he turned to one of the old sayings that might still be heard in the twenty-first century—“the parson’s children are the worst in the parish” (77). To make his point to the contrary, Moore presented a statistical analysis of the children of ministers in New England. The studies included the families of 77 ministers and 257 deacons with the data confirming, at least to Moore’s satisfaction, that the facts tell a different story and the pastor’s children are in fact not the worst (77-80). He believed it hard to conceive that such a fine result could be garnered statistically if the same questions were asked of the members of the congregations. He goes on to say the history of the church is full of examples of ministers whose children were paradigms of piety (80). One cannot but wonder if this defense of ministerial households was not prompted by his own experience at First Church.

(4) The Family as a Church

Moore’s briefest section deals with the family as a church. He clarifies that technically the family is not a church “but in the general sense…a religious institution” (82). Turning to Mal. 2:15 for his source, Moore said that the training of a righteous seed is the great object of a family institution (82). The family as a church is an ἐκκλησία, a collective organization called out (English translation) from the mass, and then united together for a religious purpose. The Christian is called out from society for the purpose of glorifying God and enjoying his blessings. Family religion is the root of correct family education and government (83). Moore then returns to an earlier emphasis, parents preparing children not only for this life but for the one to come. He commented that

family religion involves more than family worship. As all religion is included in love, so all family religion is contained in family love; and were there is this genuine love to God and one another, the family is not only a church, but an earthly type of heaven (87).

The purpose of the gospel is to call the elect to justification by faith and spiritual growth in sanctification through the gracious work of the Holy Spirit in preparation for their ultimate perfection in heaven. It is necessary that a higher idea of the family and its responsibilities be developed, which then yields greater understanding of the importance of family training that will “correct juvenile delinquency at its very source” (87).

Thoughts Regarding the Prize Essays

It may be that comparison of the articles of Hale and Grimshaw with that of Moore is inequitable because Hale and Grimshaw address solutions for dealing with existing delinquents in society, while Moore’s solution looks to affect delinquency by early training and parental guidance through the grace of Christ. Both Hale and Grimshaw include, to a degree, the importance of family and home in their essays, but in Hale’s case the family is an institutional element of the state with the children viewed as state property. Hale’s proposal for establishing institutions that distribute delinquents to state governed households and his belief “that incompetent parents” look to the government institutions to deposit their troublesome children brings into question the ability of parents to learn and improve regarding their children’s disobedience. Though Grimshaw sees the home as a place of moral teaching based on what he described as “Christian and Biblical” principles, the key to his solution was primarily through rectifying the social and environmental problems contributing to delinquency. Both Hale and Grimshaw show the difficulty faced as Christianity was challenged with sociology just as in a few years it would be responding to Darwin’s Origin of the Species that would be published in 1859. In the cases of both Moore’s competitors in the contest, the family was important, but the family yielded to the state either voluntarily or through negligence with the civil magistrate bearing the responsibility for correcting juvenile delinquency. Moore’s essay shows his Christian republican sympathies built on the Fifth Commandment as his covenantal commitment begins with the family as the foundation of society and the means to fight juvenile delinquency is first and foremost in the home.

Moore’s Later Life

Moore would continue to serve First Church, Richmond, for several more years including the trying times of the Civil War. Due to his Pennsylvania connections, Moore was asked to intercede for the parole of Union prisoners so they could return home, he also loaned paroled soldiers funds so they could have enough cash to make it home. He would spend many hours each week visiting the wounded, both from North and South in Richmond hospitals. At one point he commented that his charity might lead to him becoming a pauper. Following the war, Moore remained in Richmond but then left to become the senior minister of First Church, Nashville, Tennessee, 1869. During his last few years of life he published an article on the fellowship and unity of the church, a memorial to Gen. Robert E. Lee, and discourses concerned with young men and women wasting their lives. His deteriorating health limited his preaching in Nashville, so he wintered he in Quincy, Florida, with his friend to provide immediate care, T. M. Palmer, M. D.

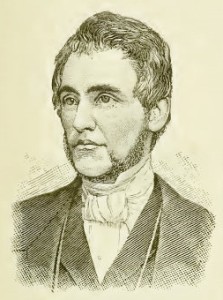

Thomas Verner Moore, D.D., died August 5, 1871, likely of tuberculosis he contracted during his war time ministry in Richmond. The hospitals, prisons, and even the Confederate soldiers gathered in camps provided incubators for disease. He was 53 when he died, but his portrait seen here seems that of an elderly man–it is hard to believe it is the same vigorous person shown at the beginning of this article. He is buried in Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Nashville. Despite specific instructions in his will that a simple and small stone mark his grave, an obelisk twelve feet high towers over the plot beneath the branches of a great tree. A committee of Nashville ministers gathered to conduct his funeral commented regarding Dr. Moore that

Thomas Verner Moore, D.D., died August 5, 1871, likely of tuberculosis he contracted during his war time ministry in Richmond. The hospitals, prisons, and even the Confederate soldiers gathered in camps provided incubators for disease. He was 53 when he died, but his portrait seen here seems that of an elderly man–it is hard to believe it is the same vigorous person shown at the beginning of this article. He is buried in Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Nashville. Despite specific instructions in his will that a simple and small stone mark his grave, an obelisk twelve feet high towers over the plot beneath the branches of a great tree. A committee of Nashville ministers gathered to conduct his funeral commented regarding Dr. Moore that

The death of Dr. Moore will be felt through the length and breadth of our church as the loss of one of its most accomplished ministers. He was a ripe scholar, a well-trained theologian, a constant, systematic student, an eloquent preacher, an assiduously devoted pastor, an able ecclesiastic, a charming friend, an esteemed and valued member of society. A sincere, ardent piety crowned the whole. In short, everything—his mental, moral, and physical characteristics, down to the form of his person and the fashion of his countenance, combined to make him, as he will long live in memory of the many who knew and loved him, a good minister or Jesus Christ.

What minister would not delight in having his life and ministry described in such wonderful terms? A truly great man had fallen in Israel.

Barry Waugh

For more information about T. V. Moore, see also on this site,

“T. V. Moore, Spirituality of the Church,” posted Oct. 20, 2021

“T. V. Moore’s Poetry,” posted Jan. 29, 2016

[1] This article is rewritten from “An Introduction to T. V. Moore Through his Essay on Juvenile Delinquency” published in The Confessional Presbyterian 7 (2011), pages 87-98; the author is grateful to the journal editor, Chris Coldwell, and its current publisher, Greenville Presbyterian Theological Seminary, for allowing me to build on the editor’s lovely presentation of the original article. The full information for the two books is, T. V. Moore, The Last Days of Jesus: The Appearances of Our Lord During the Forty Days between the Resurrection and Ascension (Edinburgh: Banner of Truth, 1981), and A Commentary on Haggai, Zechariah and Malachi (Edinburgh: Banner of Truth, 1958, 1960; one volume 1993). The header image from the Library of Congress digital online collection shows the Department for White Children of the House of Refuge, and there is also a view available on LOC of the Department for Colored Children of the House of Refuge; both complexes opened in 1850 and were located between Parrish and Brown Streets between 22nd and 24th Streets; both images are dated 1858. Grimshaw’s sketch is from his entry in History of the G.A.R. Department of Delaware, 1881-1893, by Charles A. Foster, pp. 108-109.The E. E. Hale portrait is dated 1905 and is from the Library of Congress Digital Collection, https://www.loc.gov/item/2004674906/.

[2] John Hall of Trenton, New Jersey, received 101 votes, Moore, 42; James Hoge, 2; and 1 for M. B. Hope.

[3] Some sources have his middle name as “Vernor,” but “Verner” is the correct spelling.

[4] On Presbyterians of the Past is the biography “James Blythe (1765-1842).”

[5] Moore completed studies at Princeton Seminary in 1842. Archibald Alexander would publish his book, A History of the Colonization of the Western Coast of Africa (Philadelphia: William S. Martien, 1846), wherein he the history of the colonization movement. By establishing colonies in Africa proponents returned the formerly enslaved to establish homes in freedom. Liberia was established by colonization.

[6] On Presbyterians of the Past Dr. Plumer’s “Incarnation of Christ” is available.

[7] On Presbyterian of the Past is the biography “Stuart Robinson, 1814-1881.” Also available is his fine lecture “The Churchliness of Calvinism, Stuart Robinson,” which was delivered to the First General Presbyterian Council that was held in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1877.

[8] At the time of Moore’s acceptance of the call to First Church, the women members outnumbered the men by more than two to one. In the sources, “Gwathmey” is sometimes spelled “Gwathmay.”

[9] Available online are reprints and digital copies of the winning essays within Prize Essays on Juvenile Delinquency (Philadelphia: Edward C. & John Biddle, 1855).

[10] The inclusion of Hale’s essay is unusual because when it was reprinted in the collected works he commented that: “This essay had a curious history…The essays were given to a committee who adjudged the first prize to me. Oddly enough, it happened that the essay did not meet the views of the managers of the institution. They had to print it, and did. But they accompanied it with their own views in contradiction, both the details of my plan and its principles.” (The Works of Edward Everett Hale, Vol. VIII, Addresses and Essays (Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1900), 285-320.)

[11] “Edward Everett Hale (1822-1909),” in Encyclopedia Britannica, vol. 12, 1911.

[12] W. J. Rorabaugh, The Craft Apprentice: From Franklin to the Machine Age in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), tells what it was like being an apprentice in America before, during, and after the early Industrial Revolution. His analysis shows that trade education through apprenticing declined with the growth of industry.

[13] Alexis de Tocqueville, Seymour Drescher, and Gertrude Himmelfarb, Memoir on Pauperism (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1997).

[14] Grimshaw did not cite which work of Chalmers he was referring to.

[15] The full title is, “God’s University; Or, the Family Considered as a Government, a School, and a Church, The Divinely Appointed Institute for Training the Young for the Life that is, and For that Which is to Come.”