Biographies of American historical personalities often prove disappointing for Christians anticipating serious consideration of the subject’s theological commitments within the religious environment of the era. For the Founding Fathers this can be particularly frustrating because the eighteenth century was decidedly religious whether Christian based, or a belief system that is a product of Enlightenment rationalism such as deism. The American colonial era extending to the end of the century proved crucial for the continued battle between God’s authoritative revelation of His will in the Bible and autonomous reason developing religious systems from natural revelation. Reason is good and necessary for understanding, but Christians must have reason captive to the Word of God. D. G. Hart shows in Benjamin Franklin, Cultural Protestant, Oxford, 2021, that in Franklin’s case the revelation based Puritan theology of his youth informed his religious commitment to personal and public good while denying the source and power thereof with Franklin adopting a philosophy Hart calls cultural Protestantism.

Biographies of American historical personalities often prove disappointing for Christians anticipating serious consideration of the subject’s theological commitments within the religious environment of the era. For the Founding Fathers this can be particularly frustrating because the eighteenth century was decidedly religious whether Christian based, or a belief system that is a product of Enlightenment rationalism such as deism. The American colonial era extending to the end of the century proved crucial for the continued battle between God’s authoritative revelation of His will in the Bible and autonomous reason developing religious systems from natural revelation. Reason is good and necessary for understanding, but Christians must have reason captive to the Word of God. D. G. Hart shows in Benjamin Franklin, Cultural Protestant, Oxford, 2021, that in Franklin’s case the revelation based Puritan theology of his youth informed his religious commitment to personal and public good while denying the source and power thereof with Franklin adopting a philosophy Hart calls cultural Protestantism.

The author is well qualified to write a biography of Franklin as both a general and church historian. Currently, he is Associate Professor of History at Hillsdale College, but he has also taught church history in two theological seminaries. A few of his several works include: Calvinism: A History, Yale, 2013; A Secular Faith: Why Christianity Favors the Separation of Church and State, Ivan R. Dee, 2006; and John Williamson Nevin: High Church Calvinist, P&R, 2005. When general historians write biographies about the religious commitments of their subjects they do not always grasp the nuances of their belief systems; church historians might minimalize the person’s non-religious accomplishments or in some cases not look critically at the individual and overstate piety—but these are not the case for Hart’s Franklin.

One primary source the author used to consider Franklin’s spirituality is “Articles of Belief and Acts of Religion,” 1728. Franklin was but 22 when he composed this document. Hart concluded that “Franklin’s faith was moderately heterodox” (p. 50). For one to use the work heterodox, one must accept that there is such a thing as orthodox. Oxford University Press’s world standard, Dictionary of the English Language, defines heterodox as, “Of doctrines, opinions, etc.: Not in accordance with established doctrines or opinions, or those generally recognized as right or ‘orthodox’” (1933 ed.). For Presbyterians, and Franklin did attend for a time a Presbyterian church in Philadelphia, the “established doctrines or opinions” that are “orthodox” is the summary of Scripture truth provided in the Westminster Confession of Faith and its associated documents. Orthodoxy accords with established and time-tested doctrines; heterodoxy does not accord with established doctrines. Hart makes his case throughout the book by showing where Franklin abandoned the time-tested faith of the fathers and abandoned truth.

What is it about Franklin’s faith that was “moderately heterodox”? A few of his theological views will contribute to answering this question. Franklin would “embrace a faith free from Divine revelation,” and bluntly declared “revelation indeed has no weight with me” (22). In the spirit of John Locke, reason was a better guide for living than divine revelation. As Hart quoted Locke he said, “Our business here is not to know all things…but those which concern our conduct” (38). Conduct was important for Franklin; the best religion was one that made people moral, good, and directed their activities to contribute to society as they existed under the direction of Providence. Franklin’s homelife as a lad was within the English Puritan community in Boston and his parents, Josiah and Abiah, were devout and sought to raise Ben to be a Christian. However, the boy rebelled and found deism a more attractive option, at least initially. The national founders are often called deists, but in Franklin’s case, he dabbled deeply in deism only in the end to find it wanting.

While living in Philadelphia, Franklin attended for a time the Presbyterian Church. The pastor was Jedediah Andrews whose name may be recognized because he brought charges for heterodox views against his associate minister, Samuel Hemphill. Franklin loathed the doctrinal preaching of Andrews. After five weeks of listening to Andrews he called him “disgusting” as well as “sectarian.” Franklin wanted religion that increased civic righteousness, not church piety, individuals needed most to put aside vice and achieve virtue for their own and society’s welfare (50). For Franklin, cultivating good works apart from the Puritan concept of sanctifying grace is what society really needs, not supernatural work by the Triune God (65). When Ben married his wife Deborah and they had children, he argued against having them baptized as infants in the Church of England’s Christ Church in Philadelphia. For Franklin, the doctrine of infant baptism was a creedal standard of the church, and it was divisive, sectarian. Further, he simply did not care for the organized church. Hart observed:

Of the many organizations and associations that Franklin joined, the church was not one of them…His neglect of church life, however, does not reveal antipathy to Christians as much as it shows he could not assent to the truths of English Calvinism. (128)

In response to the Hemphill case, Franklin showed disregard for the church and its creeds. Hemphill was charged with heresy in 1735 resulting in Franklin writing about the case and then tying on his leather printer’s apron to publish articles in his newspaper, The Pennsylvania Gazette. Hart discusses the article, “Dialogue between Presbyterians,” in which Franklin contended the purpose of Christianity is virtue, not faith, and he appealed for intellectual freedom from the bondage of creeds (132-3). Given his views on the organized and creedal-confessional church, it is not surprising Ben found a friend in George Whitefield whose evangelistic travels in America were accomplished outside the organized church and he also was skeptical about creeds. The two had a great friendship with Franklin admiring Whitefield’s rhetorical skill and they maintained correspondence for many years (144). Franklin’s antipathy for creeds anticipates the rise of non-confessional Evangelicalism even though he could not be considered evangelical because of his antipathy for revelation and disinterest regarding Christ’s divinity.

One aspect of Franklin’s life readers may be familiar with is his call for prayer June 28, 1787 at the beginning of sessions for the Constitutional Convention during its meetings in Independence Hall. Hart points out that by the time Franklin made his appeal, all other historical resources for developing a government had been considered but were found wanting. The Convention considered political systems from antiquity, philosophies of government, as well as other sources, but none provided what was needed. The deadlock, said Franklin, was “melancholy proof of the imperfection of Human Understanding.” It is quite an admission from one who thought so highly of reason and disparaged revelation. The prayer was not an appeal for God’s direction, but as Hart expresses it was instead “an example of the god of the gaps” (224-25). That is, if all else fails, pray to whomever is thought to be god, which for Franklin and some of his Convention colleagues was simply a nebulously defined Providence.

Telling, regarding Franklin’s heterodoxy, is correspondence with Ezra Stiles during his later years of life. Ely was president of Yale College and the two were well acquainted. In the book’s section titled, “No Deathbed Conversion,” Hart assessed Franklin’s views brought out by Ely’s inquiries. Ely was particularly concerned about Franklin’s opinion of Jesus. “Stiles,” says Hart, “was the sort of Puritan that Franklin might have become had he remained in Boston and at Old South Church,” that is a “deistic Christian” (227-8). Stiles was greatly concerned to understand Franklin’s grasp of the person and work of Christ. For Franklin, God was the creator of the universe, he governed by providence, and expected people to worship Him, and be good to others (229). Franklin’s Jesus merely taught the best ethical system in history, but as for divinity, he could not be dogmatic because he had never studied the subject. The author notes that Franklin was cagy in that he did not want to alienate people by making theological statements, after all, a rising influence on the American theological frontier was Unitarianism which denied Jesus’ deity but there were also the Presbyterians and others that held to his full divinity.

Church historian Hart’s presentation of Franklin’s spirituality may lead potential readers of Franklin to shy away believing he has nothing positive to say about him. This is not the case. As a general historian the author respects Franklin’s manifold contributions to government, science, education, and publishing in his era. In the author’s acknowledgments he comments on the presence of Franklin everywhere in Philadelphia—in street names, as the name of the bridge to New Jersey, in educational institutions such as the University of Pennsylvania and the Franklin Institute, and his importance to the American Philosophical Society as well as the Free Library system. Hart observed, “that inquisitive side is arguably his most attractive feature and may explain much of his success” (vii-viii). He attributes Franklin’s considerable success to his Puritan seeded Protestant work ethic that instilled in him a persistent passion for productive labor and as he observed further, Ben’s industry led to retirement from the printing business at 48 leaving him to pursue varied interests with a financial endowment for pursuing studies and experimentation. However, Hart points out that Franklin’s father, Josiah, had tithed Ben to the service of the church because he was his tenth son. His parents must have been disappointed that their brilliant boy had not used his gifts for Christ.

I highly recommend Benjamin Franklin, Cultural Protestant, to readers concerned for a biography balanced by the combined scholarship of a general and church historian, however in the end it is a sad story for Christians. Hart recounts in the section, “No Deathbed Conversion,” that as Franklin approached death he did not return to the supernatural gospel of English Puritanism taught to him as a youth, but he instead continued in unbelief (227-30). The author’s closing pages bring together his thoughts about Franklin and reading between the lines it seems D. G. Hart is reminding readers of Jesus’ question to the disciples, “What does it profit a man if he gains the whole world and forfeits his soul” (Matthew 16:26).

Barry Waugh

Another title from Oxford’s Spiritual Lives series reviewed on Presbyterians of the Past, is by Barry Hankins and titled, Woodrow Wilson: Ruling Elder, Spiritual President, 2019.

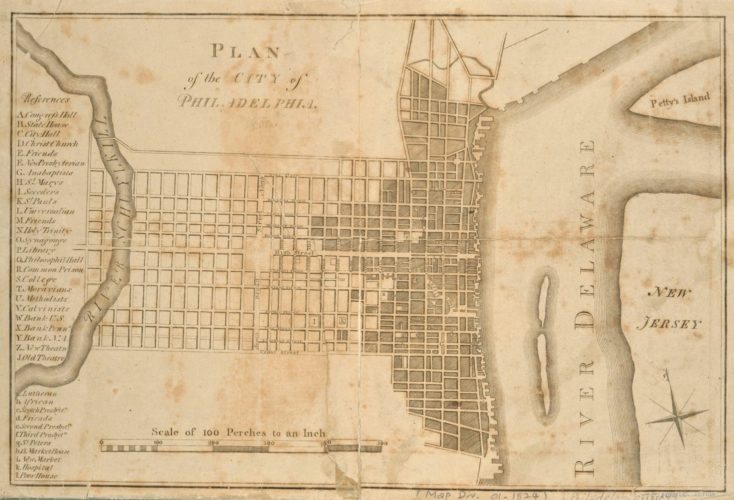

Notes: The copy of Hart’s book used was purchased by the reviewer. The header is a map of Philadelphia titled, “Plan of the City of Philadelphia,” dated 1794, four years after Franklin died; it is from the New York Public Library digital collection. See, “Observations on the Proceedings against Mr. Hemphill, [17 July 1735],” The Second Edition, Philadelphia: Printed and Sold by B. Franklin, 1735, (Yale University Library), for Franklin’s perspective on the heresy trial as posted on the National Archives website.