Philadelphia was a hub of activity when Archibald Alexander arrived in May 1807. He was relocating from his home state of Virginia to accept a call to the Third Presbyterian Church (Old Pine Street) from which after a five-year tenure he would become the founding professor of Princeton Theological Seminary. As he settled into his new situation he was overcome by the poverty in Philadelphia. There was tension within the city of brotherly love because some residents resented the arrival of not only numerous individuals of African ethnicity but also immigrants from parts of the world they thought were populated by inferior peoples. Alexander purposed to do what he could to help. He solicited ideas from his congregation first and then his fellow Presbyterian ministers that resulted in formation of the Evangelical Society of Philadelphia. Alexander drafted the constitution for the society which among other aspects stipulated that all members were to be working members. The purpose of the society was to send members out in pairs on Sunday evenings for evangelism among the impoverished. As individuals were brought to Christ and the work of the Evangelical Society expanded, it became clear that an African Presbyterian Church was needed.

Philadelphia was a hub of activity when Archibald Alexander arrived in May 1807. He was relocating from his home state of Virginia to accept a call to the Third Presbyterian Church (Old Pine Street) from which after a five-year tenure he would become the founding professor of Princeton Theological Seminary. As he settled into his new situation he was overcome by the poverty in Philadelphia. There was tension within the city of brotherly love because some residents resented the arrival of not only numerous individuals of African ethnicity but also immigrants from parts of the world they thought were populated by inferior peoples. Alexander purposed to do what he could to help. He solicited ideas from his congregation first and then his fellow Presbyterian ministers that resulted in formation of the Evangelical Society of Philadelphia. Alexander drafted the constitution for the society which among other aspects stipulated that all members were to be working members. The purpose of the society was to send members out in pairs on Sunday evenings for evangelism among the impoverished. As individuals were brought to Christ and the work of the Evangelical Society expanded, it became clear that an African Presbyterian Church was needed.

The first step was to locate a candidate to pastor the flock. Communications were exchanged with a minister named John Chavis (1763-1838). The details of Chavis’s education are not known for certain but it is likely he was tutored by John Witherspoon at the College of New Jersey. At the time of the Evangelical Society’s search, Chavis was a missionary to slaves, but even though he would have been a good minister for the Philadelphia congregation, he declined the call. Alexander and the Evangelical Society continued the search process. Candidates were hard to find because of the lack of education among American Africans whether they were free or in bondage. How could a qualified minister be found that could serve within the Presbyterian Church with its extensive education requirements?

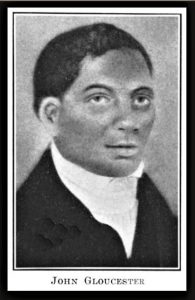

At about the time the Evangelical Society was looking for a pastor there was a candidate being prepared in Tennessee for the church in Pennsylvania. A man named Jack was born—ironically in 1776—into slavery and had been converted through the ministry of the Presbyterian missionary, Gideon Blackburn. Blackburn worked in eastern Tennessee in pastoral ministry and missions with the Cherokees. He was particularly suited for the locale and its ruggedness because he had a frontiersman way about him. Blackburn was known to keep a musket by the pulpit as he led worship in case menacing visitors interrupted services with an attack. As their friendship grew, Blackburn recognized in Jack a zeal for learning in general and an earnest desire to understand the Bible in particular, so he purchased Jack in 1806. It must have been a difficult decision for Jack because the purchase left his wife Rhoda and their children in bondage, but there was hope that in the future freedom for the whole family could be obtained. Blackburn proceeded to petition the Tennessee state government to free Jack, but his efforts failed due to the legislature’s desire not to liberate a literate slave, but undaunted Blackburn turned to the lesser magistrate. The Blount County Court freed Jack and he took a proper man’s name, John Gloucester. The surname is really a curious choice. Many former slaves chose more common surnames, so why Gloucester? A possible answer is that Prince William Frederick, second duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh, born in 1776 as was Gloucester, had opposed slavery during the controversy leading to adoption of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act in Great Britain which came into law in March 1807. There may be other reasons for the surname selected, but the coincidences are conspicuous.

John was taken under care as a ministerial student during the October 1806 meeting of the Presbytery of Union in Tennessee. With the guidance of presbytery, John studied in Greeneville College (Tusculum University). After several months of academic work Gloucester attended the February 1807 meeting of presbytery to be examined for licensure. Even though he was found to be proficient in English grammar and geography, he was not licensed due to concerns regarding his grasp of other subjects. At this point, the president of Greeneville College, Rev. Charles Coffin, intervened for Gloucester by writing a member of the Evangelical Society, Ashbel Green. Their correspondence led to Gloucester receiving an invitation to attend the approaching meeting of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church (PCUSA). When the presbyters gathered for the assembly in First Presbyterian Church, Philadelphia, Gideon Blackburn introduced Gloucester to Green, J. J. Janeway, Archibald Alexander, and others. In conjunction with Gloucester’s visit, the Presbytery of Union had submitted an overture to the assembly concerning questions about his licensure. The Assembly adopted its committee’s recommendation to refer the question to the Presbytery of Philadelphia because Gloucester would become a member of it as a minister within its bounds. The presbytery meeting took place the next month, but it referred the licensure question back to the Presbytery of Union believing it was more qualified to complete the licensing process. Even though the licensure issue was yet to be resolved, John Gloucester’s path to pastoring in Philadelphia had begun and it would lead to the founding of the first African Presbyterian church in the nation.

Financial support for Gloucester’s ministry was supplied from several sources. His salary was paid for three months each year by the Evangelical Society and funds for the remainder of each year were supplied by other entities. Beginning in 1810 a stipend was provided for three months of support each year for ten years by the PCUSA General Assembly. Private donors, presbytery and synod missionary funds, donations from interested individuals, and gifts from local churches enhanced the account. Undoubtedly, as the church matured in the faith its members contributed as well.

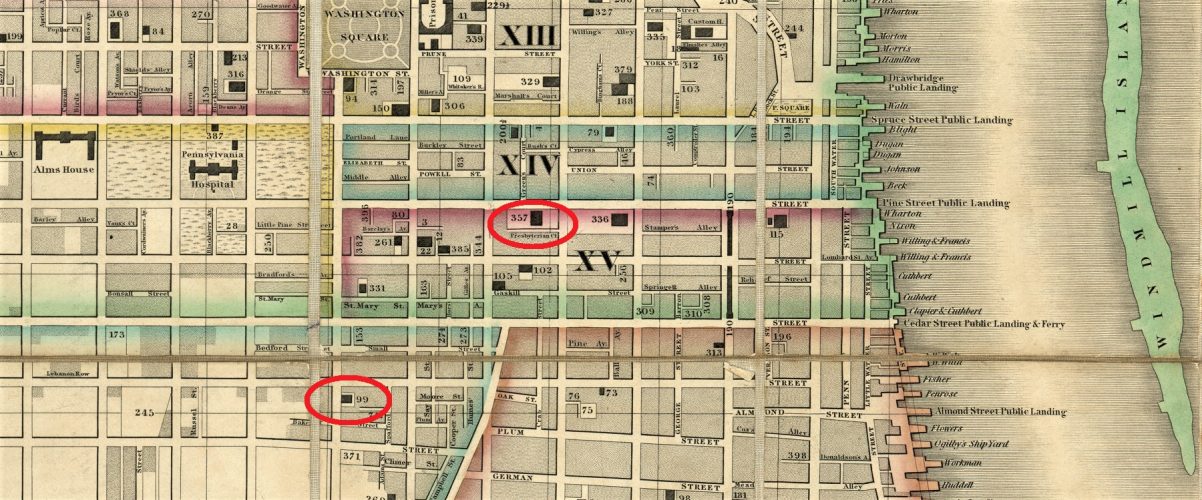

The mission was blessed with a growing congregation which meant the temporary facilities for worship needed to be replaced with a proper church building. In July 1809 the Evangelical Society agreed to “provide a house for present use,” and it sought subscriptions to buy property and erect the facility. A flyer was published to advertise the African mission and raise funds to support a work for “reformation among the blacks of this place.” Raising funds for the African church building was a difficult process but in October the Evangelical Society met to develop a plan for obtaining land. John Gloucester was present and was satisfied with the resolution that budgeted fourteen hundred dollars for purchasing a lot. The work of fund raising continued into the fall of 1810 when the Evangelical Society located a property described as “three lots on Seventh Street in the District of Southwark, between South and Fitzwater Streets, together yielding” a nearly square lot of just under six thousand square feet (see the header map). The projected cost for construction of a sanctuary was five thousand dollars, but the amount of money pledged at the time was closer to twenty-two hundred. As the work raising money struggled ahead, the plan was modified to build a smaller church resulting in reduction of the funds needed to about four-thousand dollars.

Up to this point, Gloucester had been ministering as a licentiate, but the road to ordination came to its end with his examination by the Presbytery of Union during its meeting at Baker’s Creek, April 30, 1810. It was appropriate that Gloucester’s benefactor and mentor, Gideon Blackburn, was moderator of the meeting as his protégé became a minister. Presbytery instructed Rev. Gloucester to move from Tennessee and unite with the Philadelphia Presbytery. The instruction to relocate is a bit misleading because he was already active in the African mission, but it could be the instruction was necessary to certify his work in Philadelphia was genuine. Documentation made it clear he was a freeman and not an escaped slave as he left Tennessee. Gloucester was moving from a slave state to one at the end of its process of gradually abolishing slavery as stipulated by an act passed in 1780 by the state of Pennsylvania. Rev. Gloucester’s transfer of membership was delayed a bit because he was not received into the Philadelphia Presbytery until April the following year.

As John Gloucester settled into ordained ministry in Philadelphia, he also worked to free his wife Rhoda and their four children (possibly, five or six)–James, Jeremiah, Stephen and John who were still enslaved in Tennessee (Mary and an unnamed child would be the other two). Some of his time was spent raising funds from the Philadelphia community, but considerable assistance came from church members and friends. Dr. Benjamin Rush arranged for Gloucester to preach occasionally in Princeton to help him solicit financial gifts for freeing his family. The combined efforts raised fifteen-hundred dollars so that John could purchase freedom for his family. He returned to Tennessee to complete the manumission process, so during his absence the Evangelical Society arranged pulpit supplies for First African Church. The question arises, why did Blackburn or the Presbyterian Church and Evangelical Society not bring Gloucester from Tennessee with his family? Possibly, John Gloucester was willing to suffer extended separation from his family because he was called by God to the ministry in Philadelphia, and he was willing to be separated in the short term for the hope of being reunited in the not too distant future. It was really a horrible situation for enslaved families that were often divided among different owners and Gloucester’s experience could be multiplied by thousands. It really seems the Society and the Presbyterians could have been more helpful.

Progress on the church building moved ahead as the land was prepared, then the foundation was constructed after Rev. George Potts conducted a service in the fall for setting the corner stone. The structure was completed with a dedication service May 31, 1811. Archibald Alexander preached the sermon. William Catto comments that the building was not remarkable; it was a “substantial brick church” sixty feet long by thirty-three feet wide “without any ornament about it.” The walls enclosed a room with four rows of pews, each of which had seventeen benches, and a balcony on three of the four walls giving a total capacity of over six hundred worshippers. The church served the congregation well until the years after the Civil War when it moved to a new property on a different site with a different name. A sketch drawn in 1895 that is held by the The Presbyterian Historical Society shows the original church as a frame clapboarded building while the water color painting held by The Library Company of Philadelphia dated 1884 shows the church as a brick building. The sketch is likely composed from memory or based on an original photograph, but the painting was likely composed by the artist while looking at the later brick structure in 1884. Possibly the frame structure was pre-existing and was used temporarily by First African until it was torn down for the brick building. There was mention in the sources of a place where the congregation was meeting before the corner stone was set. Catto’s account dates to 1857 and shows the brick existed from at least 1857 to 1884. History is often mystery and differing accounts are the business of historical detective work.

John Gloucester was a popular preacher in Philadelphia not only among members of First African but also individuals from other churches. Dr. Benjamin Rush often attended the African Church services because he enjoyed listening to Gloucester’s sermons. Not only could John preach, he could sing. He sometimes went to the corner of Seventh and Shippen Streets (Shippen is now Bainbridge) and started singing hymns. Once a crowd gathered, he stopped singing and began preaching from Scripture. Gloucester visited the members of his congregation as well as others who needed help. Knowing the importance of schooling and the challenges along his own road to completing an education, he spearheaded efforts to establish a school for poor children in an era when education was primarily for those of means.

John continued his labors until he contracted the red death, tuberculosis, and became so weak that he could no longer minister. He sent a letter in June 1820 to the Philadelphia Presbytery requesting supplies for his pulpit because of declining health. John Gloucester passed away on May 2, 1822. He died a young man in his forty sixth year. At the time of his passing the First African congregation had grown to over three hundred members.

The relationship of John Gloucester and the First African Church to the Presbyterian judicatories was unusual. According to Catto, Gloucester never received from the congregation a call to be its minister and was thus never installed the pastor. For his entire tenure John Gloucester was effectively a permanent stated supply. The reason given for this arrangement by the presbytery was the tenuous nature of the church finances, however one cannot help but think the presbytery was reluctant to have an African church directing itself within the rules of presbyterian government just as other churches did. Despite the lack of a pastoral call, Gloucester did not shirk his duties to the greater denomination. At the 1817 General Assembly he was an alternate commissioner who took the seat of Rev. George Potts when he had to leave the sessions. In 1828 the death of Gloucester is listed along with all the other ministers that had died that year, but the trouble is he had died six years prior. Hopefully the late death notification resulted from poor communications or a clerical error.

The account of the life and labors of John Gloucester presents a remarkable picture of a man that was freed from slavery in Tennessee, persevered as a man to buy his family’s liberty, and followed the call of God as a man to be a missionary minister in Pennsylvania. But he did not achieve his goals alone. Archibald Alexander and the Evangelical Society as well as the Presbyterian Church saw the need to help the Africans, wanted to help, and did so. Could the members of the Society have done a better job? Could they have pushed harder for First African to be as autonomous as Old Pine Street or any other Philadelphia congregation? Probably, but the Evangelical Society was working within a political, social, economic, and ecclesiastical context affecting what could be done. It is easy to look back over two-hundred years and say things should have been handled differently, but today all the facts and intricacies of people and events in Philadelphia then are not available to provide the full context of the situation. The study of history is pursued with the hope that lessons can be learned which can be applied today, so hopefully the rights and wrongs done during the life of John Gloucester have taught some lessons.

The blessings of God’s covenant faithfulness can be seen in John and Rhoda’s children whose given names were those of Bible personalities. His sons, Stephen, James, John, and Jeremiah became Presbyterian ministers with Jeremiah becoming the founding pastor of the Second African Church in 1824; Stephen’s ministerial labors led to the founding of the Central Church in 1844; James’s work led to the organization of the Siloam Church of Brooklyn, New York, 1849. Rhoda passed away April 5, 1843, according to her listing on Find a Grave.

Barry Waugh

Notes—The section of Philadelphia in the header shows First African Church marked by the lower-left ellipse and Third Church (Old Pine) marked by the other ellipse and is a section from “Plan of the City of Philadelphia and Adjoining Districts: Shewing the Existing and Contemplated Improvements,” H.S. Tanner, 1830, as from the Library of Congress Digital Collection. The portrait of John Gloucester is from the New York Public Library Digital Collection. Most helpful for this article particularly with reference to Gloucester’s manumission and then ordination experience in the church courts is George Apperson’s “African Americans on the Tennessee Frontier: John Gloucester and His Contemporaries,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 59:1 (Spring 2000): 3-19. William T. Catto’s A Semi-Centenary Discourse, Delivered in the First African Presbyterian Church, Philadelphia, 1857, provides information about Gloucester and First African and a descriptive catalog of Philadelphia’s black churches at the time of publication; also included is a brief sermon by John Gloucester. Log College Press has for download a digital copy of the charter for the First African Presbyterian Church as provided courtesy of the holding institution, the Presbyterian Historical Society in Philadelphia. On the same LCP page Gloucester’s published address to the church in 1811 is available. The charter has several “X” marks indicative of the illiteracy problem for many of the poor with the names filled in likely by Gloucester. The website for George Washington’s Mount Vernon provided the informative article “Gradual Abolition Act of 1780” by Alexandria Cannon of The George Washington University; articles and links on the George Washington’s Mount Vernon site provide reliable information regarding not only the first president but general history during his life and work. Other sources include–Elder Robert Jones, Fifty Years in the Lombard Street Central Presbyterian Church, Philadelphia, 1894; Nevin, History of the Presbytery of Philadelphia, 1888; J.W. Alexander, The Life of Archibald Alexander, 1854; and Minutes of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America from its Organization A.D. 1789 to A.D. 1820 Inclusive, Philadelphia, 274, 229, 374, 381, 450, 477, 505, 502, 534, 527, 550, 563, 587, 610, 616, 658, 683. E. T. Thompson, Presbyterians in the South, vol. 1, 207-8. Presbyterian Historical Society (PHS), collection of the Evangelical Society of Philadelphia (ESP), 52,734, RG 313, folder 313-1-2 (MS Ev 14). A copy of the one-page flyer regarding ministry to the Africans in Philadelphia titled, “To the Pious and Benevolent,” is held by the PHS in the files for the ESP, MS Ev 14. PHS-ESP, 52,734, RG 313, folder 313-1-2 (MS Ev 14), letter of June 25, 1810; letter of Oct. 24; 1810; an undated letter; letter of Dec. 10, 1810; and letter of Feb. 25, 1811. PHS-ESP, 52,734, RG 313, folder 313-1-2 (MS Ev 14). The Life of Ashbel Green, V.D.M., New York, 1849, 445, 449-453, 457-58, 450, 465, 477.