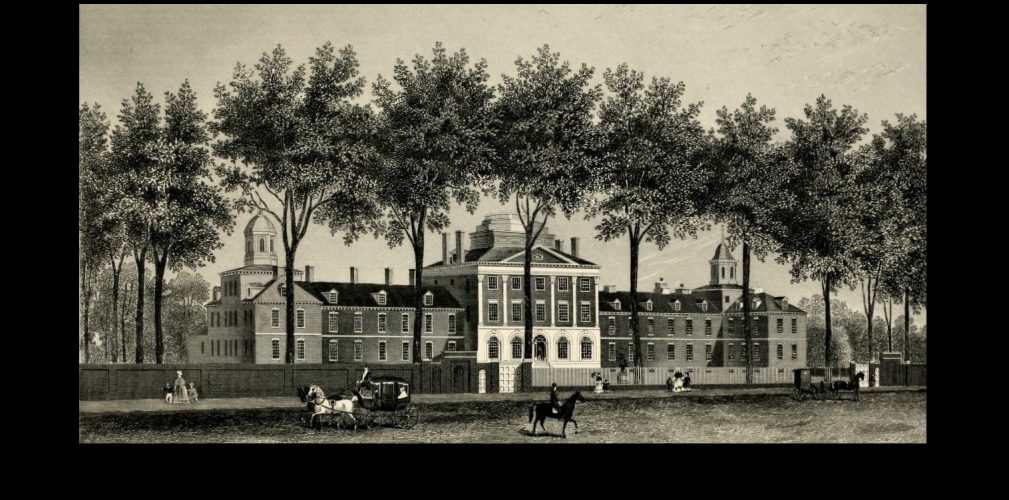

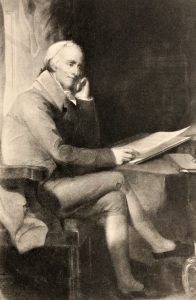

Physician and founding-father Benjamin Rush (1745-1813) published An Inquiry into the Effects of Spirituous Liquors on the Human Body, 1790. The pamphlet brought before the public several problems associated with drinking distilled spirits. As a doctor, Rush presented conclusions made from his observations of the damage spirits can cause the liver, stomach, digestion, physical appearance, and muscle tissue. His experience dealing with alcoholism in the Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia included not only treatment of its physical but also neurological aspects, and he pointed out the associated problems it caused for personal finances, family, and society. Much of what he said over two-hundred years ago could be dittoed today, however, Rush was not an alcohol abolitionist but instead proposed temperance in the sense of moderation. Doctor Rush’s Inquiry appealed to readers to consider the negative side of what they drank and his diagram “A Moral and Physical Thermometer” at the end of Inquiry (see at the end of this article) was intended to encourage individuals to modify their practices by showing them graphically the dangers of intemperance. He was concerned too that the increased availability of ardent spirits for social get-togethers often led to inebriation, and in the long term, dependency. Physician Rush believed that if someone wanted to drink beverages with alcohol, fermented juices such as apple cider and punches with minimal levels of alcohol were better than spirits, beer, and wine, but the best refreshment was made of vinegar, water, and molasses. Vinegar’s ability to kill some micro-organisms was observed with microscopes in the seventeenth century and it may have been seen as a disinfecting substitute for alcohol.

Physician and founding-father Benjamin Rush (1745-1813) published An Inquiry into the Effects of Spirituous Liquors on the Human Body, 1790. The pamphlet brought before the public several problems associated with drinking distilled spirits. As a doctor, Rush presented conclusions made from his observations of the damage spirits can cause the liver, stomach, digestion, physical appearance, and muscle tissue. His experience dealing with alcoholism in the Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia included not only treatment of its physical but also neurological aspects, and he pointed out the associated problems it caused for personal finances, family, and society. Much of what he said over two-hundred years ago could be dittoed today, however, Rush was not an alcohol abolitionist but instead proposed temperance in the sense of moderation. Doctor Rush’s Inquiry appealed to readers to consider the negative side of what they drank and his diagram “A Moral and Physical Thermometer” at the end of Inquiry (see at the end of this article) was intended to encourage individuals to modify their practices by showing them graphically the dangers of intemperance. He was concerned too that the increased availability of ardent spirits for social get-togethers often led to inebriation, and in the long term, dependency. Physician Rush believed that if someone wanted to drink beverages with alcohol, fermented juices such as apple cider and punches with minimal levels of alcohol were better than spirits, beer, and wine, but the best refreshment was made of vinegar, water, and molasses. Vinegar’s ability to kill some micro-organisms was observed with microscopes in the seventeenth century and it may have been seen as a disinfecting substitute for alcohol.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century the abuse of alcoholic beverages was a horrendous problem that displayed itself with inebriated individuals wandering streets, filling jails, and being treated by doctors. It was not uncommon for church services to be interrupted by inebriates wandering into sanctuaries. On the one hand, they were in the best place they could be to hear about Christ, but on the other hand, it was hard to do things decently and in order with lyrics filling the air such as “Let us drink and be merry, dance and joke and rejoice, with claret and sherry.” Adding to the problem was employers encouraged workers to drink. Believe it or not during industrial expansion in the nineteenth century, bosses offered free shots of whiskey to cajole workers to stay at their jobs till the end of the day. Machinery and drink do not mix, and such a practice undoubtedly caused injuries and death.

The Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA) in its report on the state of religion in 1807 commented that it deplored “in many parts, debasing intemperance in the use of ardent spirits” (p. 383). In 1811 the General Assembly thanked Benjamin Rush for his donation of 1000 copies of Inquiry that were “divided among the members of the Assembly in order to be distributed in their congregations” (467). Note that Rush had kept his pamphlet in print for twenty-one years as intemperance continued to be a problem. The next year the Assembly adopted the report of a committee appointed the previous year which encouraged ministers “to deliver public discourses…on the sin and mischiefs of intemperate drinking” and warned congregants of “those habits and indulgences which may tend to produce it.” Further, church sessions needed to be vigilant to give private warning or public censures because intemperance is “so disgraceful to the Christian name,” the distribution of temperance tracts was encouraged and encouragement was given to efforts for reducing in communities “the number of taverns and other places vending liquors” (510-11). In 1818, an action prompted by overture from the Presbytery of New Brunswick was adopted which recommended that ministers and their flocks influence “forming associations for the suppression of vice and the encouragement of good morals” and that “ministers, elders, and deacons…refrain from offering ardent spirits to those who may visit them at their respective houses, except in extraordinary cases” (684). Finally, the same Assembly recommended…

…to the officers and members of our Church to abstain even from the common use of ardent spirits. Such a voluntary privation as this, with its motives publicly avowed will not be without its effect in cautioning our fellow Christians and fellow citizens against the encroachment of intoxication; and we have the more confidence in recommending this course as it has already been tried with success in several sections of our Church (690).

Those who have been reading Presbyterians of the Past for some time will remember that some ministers in biographies were disciplined for intemperance.

The Civil War brought increased problems with alcoholism. The masses of soldiers gathered on battlefields and in forts with hours of idleness awaiting the next engagement often drank to fill the time as they played games of chance. The problem of inebriated soldiers was addressed in sermons by chaplains along with tracts written by pastors and distributed through religious publishers. Alcohol dependency was a significant problem after the Civil War ended and some temperance groups were organized specifically to help veterans.

Years before Prohibition in the 1920s there was a movement among Christians to change from using wine for the Lord’s Supper to non-alcoholic grape juice. It was a change because since Jesus served the first Lord’s Supper with wine in his chalice, wine was used exclusively up until fairly recently. But the proponents of alcohol free juice faced a problem. Grape juice ferments naturally, the process can be accelerated or retarded with temperature, additives, procedural techniques, or changing the time of harvest, but grapes will nevertheless ferment. How would alcohol free juice be produced? Two proponents of unfermented juice for Communion were Arthur (1786-1865) and Lewis Tappan (1788-1873) who were both philanthropists and devoted members of the temperance movement. Arthur in particular believed it was possible to have “pure wine,” that is alcohol free juice, so the Tappans offered a financial prize to anyone that could develop “pure wine.” Some years passed with Arthur passing away but Lewis living to see a process for alcohol free grape juice developed in 1869 when a Methodist minister-doctor-dentist named Thomas Bramwell Welch (1825-1903) developed a process for pasteurizing juice harvested from Concord grapes. His process removed the yeast that caused fermentation from grape skins. His discovery not only provided alcohol free grape juice but also laid the foundation for the processed fruit juice industry. So, if you have wondered why some churches use grape juice rather than wine for the Lord’s Supper, the temperance movement provided the alternative with grape juice even though the Lord Himself used wine and instructed his followers to do so.

Throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth Presbyterians worked to address the problems of alcohol in society, drink manufacturing, and the business of beverage distribution. Presbyterians were not the only ones promoting temperance because other Reformed churches joined the Baptists and Methodists in denominational and para-church organizations for the cause, but there were also those without religious commitments who wanted to improve society through temperance. After the division into Old and New Schools in 1837, through the division of Presbyterians at the time of the Civil War, and past the reunion of 1869, temperance was a common point of emphasis.

In 1881, the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA) established the Permanent Committee on Temperance which continued for several years under various names until it was absorbed into The Department of Moral Welfare of the Board of Christian Education in 1923. There was likewise concern about the use of alcoholic beverages in the Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS) which included churches located primarily in the South. The PCUS appears to have wanted to distance itself from promoting prohibition or temperance believing it was a political issue, but division within the church over alcohol led to disparate resolutions from the judicatories. For example, in response to a communication from the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union in 1886, the PCUS General Assembly provided the following response:

As the traffic in and use of intoxicating liquors as a beverage are the prolific causes of so much crime, poverty and suffering in our land, and as it costs the people so much money in criminal prosecutions and the support of the victims of drink, and as it is one of the greatest enemies of the Church of Christ in destroying the sanctity of the Christian Sabbath in its right observance wherever its blighting influence is felt, and as we are warned against its effects in 1 Cor. 6:10; therefore, in view of these terrible effects, this General Assembly bears its testimony against this evil, and recommends to all our people the use of all legitimate means for its banishment from the land.

It is a strong declaration. Even though many in the PCUS said it did not want to make statements about temperance it nevertheless did so. At any point in a judicatory’s sessions when the house is closely divided over an issue, the vote can go either way depending on which commissioners are seated at the time a vote is taken. However, this statement shows how the meaning of temperance evolved from moderation to prohibition. It would be more than thirty years before the ambitious goal of the temperance movement would be achieved with Prohibition via amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Rush’s “A Moral and Physical Thermometer” shows that at its extreme intemperance can lead to several vices that could end in suicide, death from disease, and the gallows for criminal behavior, while temperance leads to health, wealth, happiness, and other personal benefits. The booklet is primarily concerned with medical issues and Rush’s ethic is that of Plato because he calls for individuals to achieve excellence through virtue and avoiding vice. Sin, God, Christ, and the Bible are not in the picture for Dr. Rush. Turning to Scripture, Paul makes his case for the supernatural necessity of resurrection from the dead in 1 Corinthians 15 contending that if the resurrection is not true then “Let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we die.” Paul calls his readers to turn from bad company that corrupts morals and to awaken from their drunken stupor and seek the knowledge of God and grace of resurrection with Christ. Even though there is nothing particularly Christian about Rush’s Inquiry, the thermometer does provide Christians with a visual reminder of the dangers of intemperance. The world wants to squeeze God’s people into its mold and intemperance is one of the tools it uses. Currently, as two-hundred years ago, there is considerable drinking of alcoholic beverages. In some states over twenty percent of the adult population binge drink. Binge is defined as a single event in which a man consumes five or more drinks or a woman four or more. In one state the average binge is over nine servings. A factor that is increasing the problem is quarantining because of Covid-19. People have more time alone, become lonely, and depressed resulting in some turning to alcohol (as much as 19 percent more). But especially disturbing is in 2019, nineteen percent of youths aged 12 to 20 reported drinking alcohol within the past thirty days and 11 percent binge drinking. Alcohol is the third leading cause of preventable death in the United States behind number two, tobacco, and number one, poor diet combined with physical inactivity. How should Christians respond to this situation? Temperance has been and will continue to be a topic of debate, but the ministry of the church is to teach people to be filled with the Spirit through redemption by Christ.

Please visit the Presbyterians of the Past homepage and see the topical selections included in the recently updated “Notes & News” collection. Older entries no longer available on the homepage can be accessed in the “Notes & News Archive.”

Barry Waugh

Notes—The digitized copy of Benjamin Rush’s book used for this post was scanned from a copy held by the Army Medical Library in Washington. Alcohol use statistics are from, “Alcohol and Public Health: Alcohol-Related Disease Impact (ARDI),” “Alcohol Use in the United States” (NIH), and both “Data on Excessive Drinking” and “Underage Drinking” are on the CDC site. Both the header and the portrait of Dr. Rush are from T. G. Morton’s. The History of the Pennsylvania Hospital, 1751-1895, Philadelphia: Times Printing House, 1897. The article on Britannica.com titled, “The wine-making process,” is informative. The edition of the Minutes of the General Assembly is the volume containing minutes from 1789 to 1820 inclusive. Anne C. Loveland, Southern Evangelicals, and the Social Order, 1800-1860, LSU, 1980, has an informative chapter titled “The Temperance Reformation.” Benjamin Rush’s beverage of molasses, water, and vinegar could be switchel, which Noah Webster’s American Dictionary of the English Language, 1828, attributes to an 1800 origin but Rush might not have cared for the inclusion of rum as noted by Webster. The block quote regarding the PCUS on temperance is from Alexander’s digest, 365-66.