Obadiah Jennings was born near Basking Ridge, New Jersey, December 13, 1778, the fourth son of physician and minister Jacob Jennings. Obadiah’s father, when about forty years of age, developed an interest in reading theology and became a licensed preacher, then an ordained minister in the Presbytery of Redstone. As will be seen in Obadiah’s biography, the apple did not fall far from the tree with regard to the boy’s future. Jacob recognized that his son showed above average intelligence leading him to provide the best education available. Obadiah’s older brother, Samuel, who became a minister, observed his sibling was able to acquire knowledge readily with a keen memory and had no difficulty accessing it quickly for later use. He was enrolled in the Canonsburg Academy which would become Jefferson Academy and then Jefferson College.

Obadiah Jennings was born near Basking Ridge, New Jersey, December 13, 1778, the fourth son of physician and minister Jacob Jennings. Obadiah’s father, when about forty years of age, developed an interest in reading theology and became a licensed preacher, then an ordained minister in the Presbytery of Redstone. As will be seen in Obadiah’s biography, the apple did not fall far from the tree with regard to the boy’s future. Jacob recognized that his son showed above average intelligence leading him to provide the best education available. Obadiah’s older brother, Samuel, who became a minister, observed his sibling was able to acquire knowledge readily with a keen memory and had no difficulty accessing it quickly for later use. He was enrolled in the Canonsburg Academy which would become Jefferson Academy and then Jefferson College.

Having completed his preparatory work, the next issue was a choice of profession. Obadiah decided that his future was in law. He studied diligently with attorney John Simonson and was admitted to the bar the fall of 1800. Ready to hang out his shingle, Obadiah relocated to Steubenville, Ohio, where he practiced law until 1811. For reasons not noted, he then settled in Washington, Pennsylvania, and continued working with his law books and arguing cases. One who knew him well said that Obadiah

possessed that happy combination of talents which rendered him an able and popular lawyer. With strong intellectual powers for discrimination and argument, were united a peculiar promptitude in discovering the strong points of a case, a facility and clearness of illustration, a sprightliness of wit, and a keenness of satire, which he could employ with great effect, for the entertainment of his audience and the annoyance of his antagonist. In the language of one who knew him well, “his forte lay with addressing a jury: in this he had no superior. In an argument to the court on a point of law, when the occasion called for preparation, and required him to put forth all his strength, he was surpassed by few.”

Jennings sounds like a combination of Raymond Burr’s aristocratic portrayal of Perry Mason in the television serial combined with Andy Griffith’s down-home jurist, Ben Matlock. Regardless of any embellishment, Obadiah Jennings, Esq., was a competent attorney capable of arguing the most complex cases at the bar. However, Obadiah had a serious problem. Up to this point in his life he was moral, he respected Christian institutions, and he had the appearance of a sheep of Christ’s fold, but it was not until he was thirty that he made public profession of his faith in Christ. In a letter written April 1, 1812, Obadiah told David Hoge the factors leading up to his conversion. Hoge was an attorney and close personal friend.

I was educated religiously, and had convictions from time to time from my childhood, up to youth and manhood, I, however, still endeavored to obtain peace of conscience by entertaining a kind of half-way resolution that I would at some future time seek for religion, and it was not until a short time before I was awakened seriously to inquire what I should do to be saved, that I began deliberately to think of giving up all hopes of making my peace with God, I had gone far in the paths of iniquity, and I have reason to look back with shame and horror upon my conduct. While I was in this state of mind, sometime in the fall of 1809, while sitting in the most careless manner, hearing James Snodgrass preach—”Eternity,” upon which he was treating, was presented to my mind in such a way as I cannot possibly describe. It made such an impression on my mind that I began immediately to form a resolution of amendment. This impression was not worn off, when the sudden death of John Simonson, my law mentor, was made the means of further alarm to me. I was not long after led seriously to inquire, what I should do to be saved, I began to read the Bible, to meditate, to pray. But all only served to prove my inability to do anything of myself. I found the Bible to be a sealed book, I could not understand it. I found 1 was grossly ignorant, stupid, blind, hard-hearted, and unbelieving. Our Savior appeared to be “a root out of a dry ground, without form or comeliness.” [Isaiah 53:2] I found 1 could no more believe in Him or trust in Him for salvation than I could lift a mountain. How often was I tempted in this state of mind to give up all pursuit! Still, however, I felt and secretly cherished an opinion, or belief, that if I did but try, I could do something effectual. And every new trial, every struggle, every effort, only served further to prove my real situation, my weakness, my condition, and to discover my secret enmity against God. What hard thoughts did I entertain of that Being, who is infinite in goodness! What risings of heart against his sovereignty, and what enmity of heart against Himself! I could not see the justice and propriety of casting me off forever, provided I did all I could. I had no proper conviction of my guilt for my past horrid crimes, nor had I any proper knowledge of the spirituality, the holy nature, and inflexibility of that law of God, which is immutable in its nature, and by which 1 was justly condemned. However, after many painful struggles, vain efforts, and ineffectual attempts to make myself fit to come to Christ; after passing many dark days, and sorrowful nights, I was at length, as I hope, convinced of my sin and misery; that if I ever received any help, it must be from God; that if ever I was cured, it must be by the great Physician of souls. I was not long in this situation before God, who is Love, “revealed,” as I trust, “his Son in me.” My views of the Divine character were entirely changed.

Obadiah Jennings joined the Presbyterian Church in Steubenville, 1810, and when he moved to Washington and transferred membership, he was soon elected a ruling elder. Jennings had struggled with a sense of call to the ministry since shortly after he professed faith in Christ. He debated within about continuing at the bar or studying for pulpit ministry. Indecision frustrated him, but then he became very ill; he and the attending physicians believed he would die. But God answered prayer bringing complete recovery. Obadiah believed his life was spared so he could devote himself to the ministry. He put aside the practice of law and began a systematic course of theological reading. At the age of forty his father transitioned from medicine to ministry, and at a similar age Obadiah transitioned from the practice of law to preaching the gospel. In the fall of 1816, he was licensed to preach by the Presbytery of Ohio, and shortly thereafter received a unanimous call from the Steubenville Church to become pastor. He was ordained and installed during the spring of 1817 and continued for almost six years of service. When Pastor Matthew Brown resigned from the Washington Church to become president of Jefferson College, Jennings was a choice candidate to replace him given his history with the congregation. It was a challenging decision for Jennings because he was strongly attached to Steubenville, but friends and colleagues, even some of his congregants, advised him to take the opportunity with the Washington Church. He accepted the call and was installed the spring of 1823.

Settling into the Washington Church was not too difficult. Many of the congregants were familiar to him which made the transition easier. Obadiah was increasingly suffering health troubles and after five years tenure he moved from Washington to the Presbyterian Church in Nashville, Tennessee, April 1828. At some points, he had to take extended absences from his new church because of weakness. When able to do so, Obadiah worked hard with his own and other churches in the Nashville area. His last months were a physical struggle and in his last days Jennings

asked his wife to repeat to him the answer to the question in the Shorter Catechism [Q 27], “What benefits do believers receive from Christ at their death?” and several times afterwards repeated with great delight, “the souls of believers are at their death made perfect in holiness, and do immediately pass into glory.” Thus while his mind was absorbed in the contemplation of those glorious prospects which were opening upon him, he sunk, with peaceful serenity, into the slumber of death.…

Rev. Obadiah Jennings, D.D., died January 12, 1832, at the age of fifty-four. His total years of ministry were only fifteen and they were distributed among three churches. The funeral sermon was preached by Obadiah’s friend, William Hume. Scotsman Hume had been sent by the Synod of the Secession Church to be a missionary to America, and he was president of the Female Seminary of Nashville and Professor of Ancient Languages in Cumberland College. Even though both calls extended about five years, the Steubenville and Washington churches held memorial services for Jennings as well. He is buried in the Nashville City Cemetery with his grave marked by a fine obelisk styled monument. Obadiah was married twice. The first marriage was during his Steubenville call to Mary Becket of Westmoreland, Pennsylvania, who apparently died from complications related to delivery of an infant daughter named Lucinda. The second marriage was to Ann Wilson and she had seven children, two boys and five girls–Thomas Read, Ann Elizabeth, Mary Stuart, James D., Rebecca Stuart Read, Sarah, and Ellen. According to J. A. Thompson in New Bible Dictionary, Second Edition, there are at least twelve men named Obadiah in the Old Testament and the name means “servant of Yahweh” or “minister of Yahweh.” There was no way for Obadiah Jennings’s parents to know that their son would become a minister, but they chose the right name.

Among the honors and important events of Obadiah Jennings’s life were Jefferson College granting him the A. M. in 1821 and the College of New Jersey (Princeton) presenting him the Doctor of Divinity in 1831. He was an original trustee, 1806-1808, when Washington Academy was incorporated and was then elected a trustee serving, 1812-1828. He was honored by his presbyter peers when chosen for the moderator’s podium for the General Assembly of 1822, and he delivered the annual missionary sermon during the sessions the evening of May 21. General Assembly that year was lengthy extending thirteen days, May 16-28. Some items of business transacted included the needs of ministerial education for poor and pious youth as the Assembly pressed (chastised) presbyteries to contribute funds; an overture from a church regarding a decision by the 1821 Assembly concerning a man who married his deceased wife’s sister; the processes required for the union of the General Synod of the Associate Reformed Church with the PCUSA were completed; adopted were forty rules for assembly procedures, which interestingly, were to be read by the retiring moderator before surrendering the podium to the moderator elect; discussion of psalmody in the denomination; and it was decided that the newly published digest of the General Assembly—a catalog of its actions was “authorized to” be placed “in the hands of responsible booksellers, for sale on commission.” Imagine a nation in which someone would walk into a bookstore from the street and inquire, “Might you have a copy of the PCUSA digest of the General Assembly?” However, the most important decision made in 1822 concerned the doctrinal future of the PCUSA because Charles Hodge was elected Professor of Oriental and Biblical Literature at Princeton Seminary. As he moved to three other professorships, Hodge would influence the PCUSA and American Christianity in general until his passing in 1878 (56 years of teaching). It was an eventful Assembly, surely a tiring one, but also one of the more important ones.

Some of Jennings’s sermons and discourses were published in pamphlets, one of which was entitled The History of Margaretta C. Hoge: Who Died May 6, 1827: Written for the American S.S. Union, and Revised by the Committee of Publication. In honor and remembrance of Jennings, his debate with Alexander Campbell was published with a memoir of him by “Rev. M. Brown” bearing the title, Debate on Campbellism, held at Nashville, Tennessee: In which the Principles of Alexander Campbell are Confuted, and His Conduct Examined, Pittsburgh, 1832; the memoir constitutes 22 of the 260 page book. Alexander Campbell (1788-1866) was one of the founders of the Disciples of Christ. He was influential in Kentucky, Tennessee, Ohio, Indiana, and West Virginia. His theology was often confronted by Presbyterians due to his opposition to Calvinism, teaching of baptismal regeneration, and ardent anti-confessionalism.

Barry Waugh

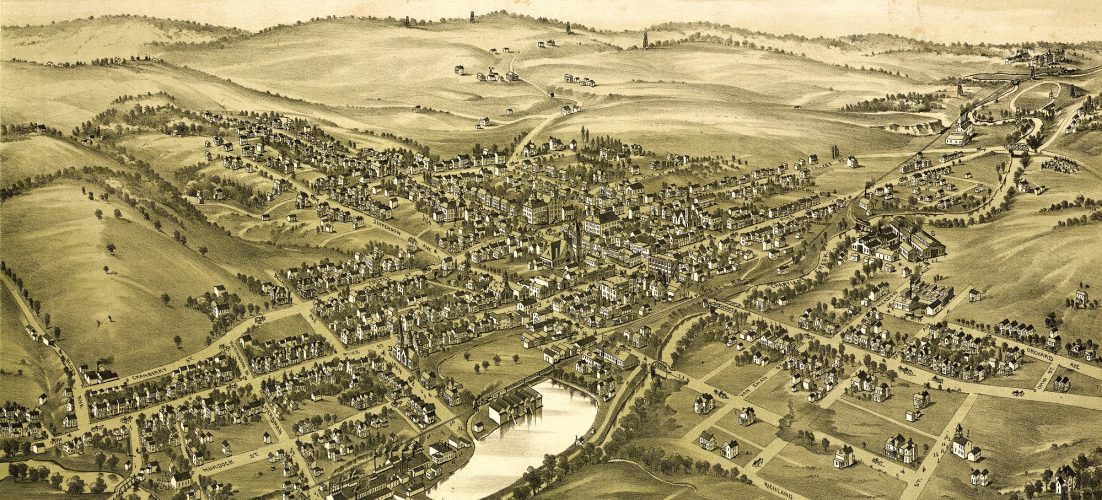

Notes—The header is snipped from an 1897 view of Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, by T. M. Fowler as available from the Library of Congress digital map collection; at the center just above the pond-like area is the campus of Washington and Jefferson College. The portrait and descendants information is from, A Genealogical History of the Jennings Families in England and America, vol. 2, The American Families, 1899, by William Henry Jennings. The biography in Sprague’s Annals of the American Pulpit, vol. 4, and the memoir of Jennings in the book mentioned previously have the same information; Sprague provides an edited form of the memoir. Also, some information was found in nineteenth-century publications concerning Washington and Jefferson College.