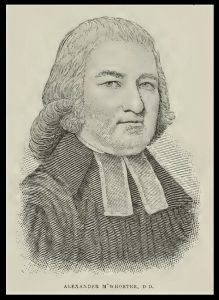

Alexander was born July 15, 1734, to Hugh and Jane McWhorter in New Castle, Delaware. Hugh was a successful farmer who settled in America after having made a sizeable sum selling linen in County Armagh, Ireland. The family picked up roots at the urging of their eldest son, Alexander, who died while studying theology at the University of Edinburgh and never made it to the American colonies. It was not uncommon for parents to use the name of a deceased child for a newborn and this is the case for the current biographical subject when he was born the eleventh child. Alexander’s studies after his father died in 1748 were received in North Carolina where Jane had moved to join other family members but Alexander left North Carolina after a short time to study at Nottingham Academy with Samuel Finley (as had Joseph Alexander). He graduated the College of New Jersey in 1757 and studied theology with William Tennent before receiving licensure by the Presbytery of New Brunswick in 1758. In the fall he married Mary Cummings. While supplying pulpits within his presbytery he preached in First Church, Newark, which soon issued a unanimous call that he accepted. McWhorter was installed in 1759 and served until 1764 when the Synod of New York and Philadelphia (highest judicatory at the time) appointed him a missionary to North Carolina. At this point, the sources provide a confused account of the remainder of his life, but it can be said that he worked for several years in North Carolina pastoring, supplying pulpits, and teaching or directing schools. At some point he was offered a call to a church in Charleston, South Carolina, but he turned it down. In 1781 he returned to First Church, Newark, to continue there until he died July 20, 1807, from injuries received when he fell off a horse. Alexander McWhorter was buried in the First Church cemetery. He and Mary had five children. With respect to the Revolution, he was a chaplain and involved considerably with political aspects of independence as related by William B. Sprague’s Annals of the American Pulpit, but particularly by James McLachlan’s biography in Princetonians 1748-1768. MacWhorter was on the committee with John Witherspoon that compiled and edited the first edition of The Constitution of the Presbyterian Church published in 1789; he served on sundry committees of the church; and was moderator of the General Assembly in 1794. His educational interests included service on the board of the College of New Jersey, 1772-1807, and his leadership was honored by Yale with the Doctor of Divinity in 1776.

Alexander was born July 15, 1734, to Hugh and Jane McWhorter in New Castle, Delaware. Hugh was a successful farmer who settled in America after having made a sizeable sum selling linen in County Armagh, Ireland. The family picked up roots at the urging of their eldest son, Alexander, who died while studying theology at the University of Edinburgh and never made it to the American colonies. It was not uncommon for parents to use the name of a deceased child for a newborn and this is the case for the current biographical subject when he was born the eleventh child. Alexander’s studies after his father died in 1748 were received in North Carolina where Jane had moved to join other family members but Alexander left North Carolina after a short time to study at Nottingham Academy with Samuel Finley (as had Joseph Alexander). He graduated the College of New Jersey in 1757 and studied theology with William Tennent before receiving licensure by the Presbytery of New Brunswick in 1758. In the fall he married Mary Cummings. While supplying pulpits within his presbytery he preached in First Church, Newark, which soon issued a unanimous call that he accepted. McWhorter was installed in 1759 and served until 1764 when the Synod of New York and Philadelphia (highest judicatory at the time) appointed him a missionary to North Carolina. At this point, the sources provide a confused account of the remainder of his life, but it can be said that he worked for several years in North Carolina pastoring, supplying pulpits, and teaching or directing schools. At some point he was offered a call to a church in Charleston, South Carolina, but he turned it down. In 1781 he returned to First Church, Newark, to continue there until he died July 20, 1807, from injuries received when he fell off a horse. Alexander McWhorter was buried in the First Church cemetery. He and Mary had five children. With respect to the Revolution, he was a chaplain and involved considerably with political aspects of independence as related by William B. Sprague’s Annals of the American Pulpit, but particularly by James McLachlan’s biography in Princetonians 1748-1768. MacWhorter was on the committee with John Witherspoon that compiled and edited the first edition of The Constitution of the Presbyterian Church published in 1789; he served on sundry committees of the church; and was moderator of the General Assembly in 1794. His educational interests included service on the board of the College of New Jersey, 1772-1807, and his leadership was honored by Yale with the Doctor of Divinity in 1776.

As was often the case in McWhorter’s day, his two volumes of sermons were published at the request of a group of subscribers who pressed “with much importunity” upon him “to submit to this business” of publication because of “kind and peculiar [independent] friends, to whom it was difficult for him to refuse anything.” After informing readers in his preface that the sermons were never intended to be published and thus no citations are provided for the several sources he accessed, he expressed his opinion about controversy in the pulpit.

In these Discourses, he has avoided the intricacies of controversy; because it never was his custom to carry such things into the pulpit, neither did he ever observe much good arising from it. His mode of preaching has been to Inculcate upon his people the great doctrines and duties of the gospel; and if the plain truth of religion will not be beneficial to souls, it is not probable disputation will be of much service in promoting the sweet, tender and blessed spirit of Christianity.

For McWhorter, sermons were simply to set forth the truth given in Scripture as presented in the Westminster Standards. Even though he says he avoided controversies in the pulpit, the sermon transcribed below makes some mildly speculative and controversial points. It was McWhorter’s hope that his forty-four years of experience behind his sermons provided the younger generations a theological source “that when he should be dead, he might still preach unto them.” And the members of his congregation who subscribed for the 204 copies likewise hoped the sermons would provide “benefit of us and our children.” Publication in the day was often either paid for by the writer, or as in this case by subscribers, thus the limited and specific number of copies. Books were printed as a stack of pages and purchasers would have their copies bound. To be asked to have anything published was a great honor and funding by subscribers was the icing on the cake.

McWhorter describes in his sermon the covenant as a product of God’s condescension, which emphasizes the sovereign nature of its administration. Since the covenant in general and that of works in particular shows divine condescension, the administration of the covenant of works is unilateral and not a bilateral agreement between God and man as though they were equals negotiating a deal. The Administrator stipulated that the crown of creation, Adam, must submit to the covenant of works—there was no alternative. With regard to the consequences of the fall for the image of God in man, McWhorter holds that the image was lost completely and only through the grace of salvation can it begin restoration that is ultimately completed in glory. His view was commonly held by some Reformers and his contemporaries, but John Calvin taught instead that if man totally lost the image of God through the fall, then man would not be man. Calvin believed the imago Dei was catastrophically damaged by the fall, not completely lost, but through salvation the process of repair begins leading to ultimate restoration in the perfection of glory. McWhorter then emphasizes that fallen man is instead in the image of Adam from generation to generation (Genesis 5:3) until grace begins renewal of the imago. Interestingly, he turned to Esdras for Jewish commentary concerning the results of the fall on Adam’s posterity (Do we forget to consider Jewish comments on pre-incarnation subjects?). There is emphasis on federal headship throughout the sermon both respecting the one who fell and the One who restored. The sermon reads well and McWhorter sticks to his subject, which is not always the case with discourses from his era. There are allusions to the Westminster Standards, but McWhorter makes no explicit references to them. The sermon is from pages 106-116 of volume one of A Series of Sermons, Upon the Most Important Principles of Our Holy Religion, In Two Volumes, by Alexander McWhorter, Newark: Printed by Pennington & Gould, for the Author, 1803.

The header image of Genesis 2:16-17 is from the King James Version, 1611, and the portrait of MacWhorter is from Nevin’s Presbyterian Encyclopedia.

Barry Waugh

Sermon IX

The Primitive Covenant Made with Man, or The Covenant of Works

Genesis 2:16-17

And the Lord God commanded the man, saying, of every tree of the garden, thou mayest freely eat; but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, thou mayest not eat of it; for in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die.

As we have contemplated man in his primitive state of rectitude [previous sermon] as he came pure and perfect from the hands of his Maker, let us now consider the privileges he enjoyed, and the peculiar advantages under which he was placed for the service of his God, and the continuation of his felicity. He was, in a high degree, a favorite of heaven, and great immunities and privileges were granted to him, far beyond what a mere creature, however perfect, could, according to the strict laws of creation demand. Reason seems to require, that if God make a rational creature, for his service, that he should be perfect in his kind, and endowed with every qualification and accomplishment, necessary to enable him to answer the end of his creation, and for the continuance of his own happiness. It seems to be inconsistent with the justice and goodness of Jehovah, to form a creature in a state of sin and misery, or in such circumstances that this must be the necessary and unavoidable consequence. There appears nothing to an eye of reason inconsistent with the benevolence and holiness of God, to create a rational being in a state of perfect righteousness, with powers to yield obedience to his will, and by such obedience, to continue and increase his own felicity, without stamping upon him immutability, or an impossibility of falling. This was the very state in which man was created, and no doubt the state of the angels too. They were created perfectly holy or good, yet in their nature capable of sinning; hence, multitudes of them fell, but much greater multitudes of them stood in the love and service of their Maker and will continue to stand in glory and blessedness forever.

Man, in his original state of innocency, had not only conferred upon him everything which the laws of creation required, but inconceivably more—innumerable favors and honors were granted to him besides. He was placed in Eden, in a garden of pleasure, planted by the hand of the Almighty, with every fruit tree, and every flower, which could please the eye, regale the senses, or gratify the taste. To him was given dominion over every creature, so that he was constituted sole lord of the whole creation. He had the most intimate converse and unreserved communion with God. And besides all these dignities and honors, his Creator was pleased in astonishing condescension and grace, to enter into a covenant of life with him, which is commonly styled, to distinguish it from all others, the covenant of works. Before we enter upon the consideration of the nature and conditions of this covenant, or to bring forward the proofs, that such a covenant did really exist, there are two questions here, which are frequently asked. They are rather matters of curiosity than moment, and everyone answers them according to the conjectural opinion of his own mind, without the infringement of any useful doctrine of religion.

The first question is, how long did Adam continue in his state of innocency and happiness?

Various have been the conjectures in reply to this question. Some, in running [showing] the similitude between the first and second Adam, have supposed the former maintained his rectitude, as long as the latter lived upon earth; if so, he must have supported his innocency for more than thirty-three years at least. Many others have supposed that he fell the evening of the day in which he was created. But the greatest probability lies between these distant opinions. Upon the whole, after viewing all the conjectures on this subject, and as the scriptures are entirely silent upon it, it is most probable he did not hold his integrity for years, or even months—yet it is very likely to me, he stood for a number of days, perhaps a few weeks. We know there was business done between the creation and the fall, which must have taken time. It is probable that Eve was created the same day with her husband, and we find the next day sanctified for a sabbath, when all still remained very good. After this, we find the garden of Eden planted, the man put into it with various directions given him, the covenant of nature or works was entered into, and all beasts of the earth, and fowls of the air passed before Adam, to receive their names according to their respective species. Eve must have suffered the temptations of the serpent, Adam the enticements of his wife [to sin], and all these things must have taken up some time. They could not have been done in a few hours. It is rational to suppose, they must at least have occupied a number of days. For though God can do all things in an instant, yet man must have a rational portion of time for every purpose or work. Therefore, upon the lowest estimation we can form, there must have been a number of days between the creation of man and the fall.

A second question is, could Adam and Eve be naked during their state of innocency, and be ignorant of it?

Immediately after their eating the forbidden fruit, the sacred text informs us, “That the eyes of them both were opened, and they knew that they were naked.” This seems strongly to imply that they knew not this circumstance before. And there is another text previous to this, affirming the matter of their nakedness. “They were both naked the man and his wife and were not ashamed.” The reality of this circumstance, as it has always appeared to me, though it is only a matter of private opinion, was briefly this: They were not covered in their innocent state with anything which we now call garments, or covering of any kind, as they afterwards were. Yet I apprehend they had a dress of a celestial nature, that their bodies were surrounded with a bright shining glory, as an external evidence of their own innocence, purity, and perfection, and also as a token of the divine presence and favor. They were clothed in such glory as that in which sometimes angels have appeared; in such glory as shone upon Moses’ face, when he had descended from the mount after having been forty days in the presence of God; such glory as enveloped the burning bush, which was not consumed; such glory as rested over the mercy seat between the cherubim in the tabernacle and in the temple; such glory as surrounded the body of Christ at his transfiguration; and such glory as the saints shall be clothed in at the resurrection. The saints, at the resurrection, will be dressed in white, splendid, and celestial robes, and these shall be their glorious covering throughout eternity. Hence, we read in the resurrection, there will be celestial bodies, spiritual bodies, and that the saints shall be raised in glory. If these things be just, then it is nothing strange, that our first parents, upon their transgression, found themselves naked. Immediately this heavenly apparel, this glory which surrounded their bodies departed from them, as well as the image of God, and holiness from their hearts, and here they were naked; indeed, they became instantly naked both in soul and in body. This image of God, will be re-produced in the soul of the saint at his conversion by the second Adam, and perfected therein after death, when it shall be received to heaven—but the body, the wretched body, shall not be clothed again with its original glory, until the resurrection.

But enough of these conjectures: it is time we should proceed to consider the nature and conditions of the covenant of works, and produce the scripture authorities, that such a covenant did really exist.

As to the nature of this covenant entered into between the Creator and his creature, it must always be remembered to be very different in many respects from covenants entered into between man and man. A covenant agreed upon between men for mutual offices to be performed, and mutual benefits to be received always supposes an equality in the parties simply or in some degree; that they have it in their power to perform the reciprocal good offices [duties, responsibilities], and that they are not under obligation to the performance of them without such a bargain or agreement; but certainly no covenant of such a nature can possibly take place between God and man, because there is no equality or proportion between them, that neither the blessings God promises by covenant, nor the offices or duties which man is held to perform, can be of any reciprocal advantage, or of any benefit or utility to God, “Can man be profitable to his Maker, or can his goodness extend to the Most High?” Because also, man without any covenant is obliged to perfect and holy obedience to the divine will; and he is likewise wholly dependent upon God for all strength and ability for the performance of every good thing. Yet the great Supreme, in the superabundance of his goodness and condescension to his creatures, hath been pleased of his love and good pleasure to deal with them in the way of covenant. Indeed, God might have justly demanded perfect obedience of man as his Creator, without any promise of reward, but that he might temperate [moderate] his sovereign dominion with the highest goodness, he entered into covenant with him which should consist of a promise of reward on his part, and the performance of perfect obedience on the part of the creature man. Thus Jehovah, at the same time, shews forth his almighty power, and demonstrates the exceeding greatness of his beneficence and love to him. Hereby he ensures communion with himself, and happiness to man, and binds him to himself by the strong and endearing bond of mutual affection and mutual obligation. Thus, God binds himself to man, and engages to confer upon him immortality and interminable felicity upon the condition of steadfast fidelity and unfailing obedience.

This is the nature of the covenant which God made with man at his first creation, which is sometimes called the covenant of nature, a legal covenant, or more usually the covenant of works. It is styled the covenant of nature, not by reason of a natural mutual obligation, of which no such thing can possibly take place between God and man, but because when man was primitively formed, there was founded in his nature sufficient righteousness and strength to perform his Maker’s commandments. It is called a legal covenant, because the condition of it, on the part of man, was to conform to the law of nature, which was originally inscribed upon his heart. And the covenant of works, because it was by holy works, or by perfect persevering obedience, he was to fulfill all righteousness, and be entitled to the reward of eternal life.

Now, that God made a covenant of this sort with man in his primitive state of rectitude, may be abundantly established from various passages of sacred scripture, of which, at present, I shall only select a few.

This may be argued from the words of our text. “And the Lord God commanded the man, saying, of every tree of the garden thou mayest freely eat, but of the tree of knowledge of good and evil, thou mayest not eat of it, for in the day that thou eatest thereof, thou shalt surely die.” As Adam was under a law, the sanction of which was mortality or death, in case of transgression, and there was a sign and seal annexed to it, to wit, the tree of knowledge of good and evil, of which he was by no means to eat, otherwise he should lose all his glory, immortality, righteousness, holiness and felicity, and immediately become mortal in the utmost extent of the threatening; so it is certain on the other hand, that God also gave him a covenant of life, promising him that if he eat not of the forbidden fruit, he should be established and confirmed in all his glory, dominion, and happiness forever. There was another tree also in the midst of the garden, which was appointed a sign and seal of this part of the covenant, called the tree of life. He was to partake of the one as a seal of his confirmation in bliss and immortality and avoid the other as the sure source of perfect destruction. Hence, after his folly, wickedness and disobedience, God would not suffer him to taste of the tree of life, “Lest he should put forth his hand and take of the tree of life, and live forever, he is expelled from the garden of perfect pleasure and felicity. So, God drove out the man.” These things clearly show that there was a covenant entered into between God and man at his first creation.

This is further evident, from a covenant of works being repeatedly mentioned by Moses, in other parts of his writings. “He that doeth these things shall live in them.” This covenant is often referred to by St. Paul in his epistles, when he says, “The man that doth the commands shall live by them.” This he also denominates the law of righteousness, which entitles a man to the promise of life, and it is called, “The commandment of the law, which was ordained to life.”

That God made a covenant with Adam at his first formation, we are assured of by the prophet Hosea, when he declares, “They like men have transgressed the covenant.” In the original it is, “They like Adam have transgressed the covenant.” And if it had been thus translated, the sense would have been more clear, and the idea more accurately expressed. This must administer conviction to every mind, that Adam was under a covenant of blessedness and life, as well as under a law which threatened a curse and death. The great difference between a law and covenant is, that the former menaces with a penalty every transgression of it—but the latter, promises remuneration in case of an exact obedience. Where there is nothing but pure precept and penalty, that is a law—but where there is a compensation annexed for the observation of the precept, there is a covenant. Perfect law rewards not, but punishes the disobedient; but a covenant always promises and remunerates those who fulfil the conditions of it. Adam, for his transgression, had death inflicted on him according to law—but if he had continued obedient, he would have been recompensed with life, glory, felicity, and immortality.

But the grand difficulty in this matter of covenant, is God’s selecting Adam and constituting him head and representative of all his posterity, and as he conducted, so should be their fate. This is a matter which has employed the abilities and pens of the great and learned for many ages, and it would be highly absurd and improper, for anyone to thrust himself into the seat of judgment, as thousands and tens of thousands have done, wherefore, I shall only lay before you in the briefest manner, what appears to me the scriptural representation upon this subject. And this representation, after a long and close investigation, irresistibly decides to my mind, that in the covenant of works, Adam was the head and representative of all his posterity. I have not time to produce the arguments from the nature and reason of things, or existing circumstances, on this occasion, but only mention the scripture texts in favor of it.

We are soon Informed that Adam propagated his posterity, not in the image and likeness of God, in which he himself was created, but in his own sinful likeness and image, without righteousness, and without holiness, destitute of external glory and internal goodness. “He begat a son in his own likeness, after his own image.” And thus all his posterity have propagated their offspring sinful and mortal, down to the present day. This shows that he was the head and representative of all his progeny. In the book of Job, the same thing seems to be expressed :—”What is man that he should be clean, or the son of man that he should be righteous? Who can bring a clean thing out of an unclean? Not one.” The Psalmist David also declares the same matter in the afflicting language of lamentation.” Behold “I was shapen in iniquity, and in sin did my mother conceive me.” These things demonstrate that a degeneracy and sinful corruption was conveyed from one generation to another; and the same must have descended from Adam, and therefore, that he was the head and representative of the whole race.

Arguments innumerable might be drawn from the most eminent Jewish writers, in support of this doctrine, of which I shall only quote this one from the second book of Esdras. “O thou, Adam, what hast thou done? For though it was thou that sinned, thou art not fallen alone, but Ave all that come of thee.”

But the apostle Paul establishes this doctrine beyond all rational contradiction. Hearken to what he affirms in various places, “As by one man’s sin death entered into the world, and death by sin, so death passed upon all men, for that all have sinned. By the offence of one, judgment came upon all men to condemnation. By one man’s disobedience many were made sinners. Through the offence of one many are dead. Death reigned from Adam to Moses, even over them that had not sinned after the similitude of Adam’s transgression,” that is, infants who had not committed actual sin. But there would be no end of producing authorities to evince the absolute certainty of this important truth, that Adam was taken into covenant by God as the federal head and representative of all his posterity, or of all mankind. As he should conduct himself, so it should fare with them. If he should behave well and be obedient, they would be all happy, holy, and glorious forever; if he should conduct amiss and transgress, then all must suffer the penalty of the broken covenant, all must die.

Before I close this subject, a few words must be said respecting the sanction of the covenant of works. “In the day thou eatest thereof, thou shalt surely die.” What is the import of the death here threatened? It must evidently be correspondent, or co-extensive to the life, which Adam enjoyed, and the continuance of it promised upon his persevering obedience.

This consisted of three great articles: natural, spiritual, and eternal life—so the reverse must be natural, spiritual, and eternal death. In the day Adam eat [ate] of the forbidden fruit, and at that very hour, he became mortal. He had forfeited his natural life, and God might take the forfeiture of him, and all his posterity, whensoever he pleased, which has actually and universally been done. In the same unhappy hour, he also lost his spiritual life; holiness departed from his heart, and all his glory and happiness forsook him, and he became dead in trespasses and sins, as all his progeny are. He likewise lost all claim to immortal felicity. And immortality, without happiness, is a curse and not a blessing. Therefore, he had incurred the awful curse and indescribable doom of death eternal.—But it is time I should finish this subject, in a very few reflections.

First, we may reflect, whatever may have been the misconduct of Adam, and the state of mankind in all generations, yet God’s throne is clear, and iniquity is not to be imputed to him. God cannot be the author of the fall of man, or of any sin, either directly or indirectly. Whatever we may charge upon man, let us always beware of charging God foolishly. Whatever may be our blindness, darkness, and ignorance, respecting the introduction of sin into our world, and when we shall have proceeded in our investigations, as far as rational and scriptural disquisitions will carry us, and we find new difficulties in our course, let us, in want of satisfaction, take all blame to ourselves, and ever acquit and vindicate the ways of God. Whatever man may think, believe and do, the great Supreme is, “A God of truth, without iniquity, just and right is he. God is just in all that is brought upon us. There is no iniquity with the Lord, Surely God will not do wickedly. And shall mortal man be more just than God?”

Secondly, we may reflect, that however man hath sinned and come short of the glory of God, this cannot in the least impair or dissolve his obligations of love, gratitude, and duty to his infinitely glorious Creator. Everyone will readily acknowledge, that the crimes and perverseness of malefactors do not dissolve their obligations of obedience to good laws, or in the least impair a righteous government. Evil conduct in such cases, in the common sense of mankind, always aggravates their offences, and heightens their transgressions. Therefore, we are under the same obligations of love, service, and homage to God, as if we and our first parents had never sinned against him.

A Third reflection is, that we ought to love God with all our hearts and praise him for once placing us in such happy and dignified circumstances, as well as to abase ourselves in the deepest humiliation and repentance, that we have wickedly fallen from that blissful state, and perversely rejected all our privileges, honors, and happiness. O man, thou hast destroyed thyself. How art thou fallen, O thou favorite of heaven? Alas, man being in honor abideth not. O let all the children of men humble themselves before their offended God, and repent in dust and ashes, and return unto him with your whole hearts, if so be, he may yet have mercy upon you.