James Latta was born the winter of 1732 in Ireland to Scotch-Irish Presbyterian parents. His father was likewise named James, but his mother, surnamed Alison, was related to American Old Side Presbyterian minister, patriot, and educator Francis Alison who was steeped in the Scottish common-sense realism school of Francis Hutcheson at the University of Glasgow. Alison would influence James greatly. James’s parents emigrated to the American Colonies when he was about six years old. The ship wrecked on the coast and all family records were lost along with much of their property. They settled near Elkton, Maryland, where they attended the Presbyterian church at Elk River which came to be called Rock Church. It is believed his parents are buried in the church yard.

James Latta was born the winter of 1732 in Ireland to Scotch-Irish Presbyterian parents. His father was likewise named James, but his mother, surnamed Alison, was related to American Old Side Presbyterian minister, patriot, and educator Francis Alison who was steeped in the Scottish common-sense realism school of Francis Hutcheson at the University of Glasgow. Alison would influence James greatly. James’s parents emigrated to the American Colonies when he was about six years old. The ship wrecked on the coast and all family records were lost along with much of their property. They settled near Elkton, Maryland, where they attended the Presbyterian church at Elk River which came to be called Rock Church. It is believed his parents are buried in the church yard.

For his education James was directed by kinsman Francis Alison who at the time was pastor of the church in New London, Pennsylvania, and he was the master of a classical school named New London Academy. The school was the beginning of what is now the University of Delaware. This was the school, which the Synod of Philadelphia (Old Side) adopted in 1744 as its own and paid salaries to the master using funds gathered from the churches. The academy was primarily intended to prepare candidates for the ministry. At least initially, the school offered a free education in classical languages, philosophy, and divinity to any family willing to enroll children. Several of the graduates taught by Alison became well known for their public service, judicial acumen, and of course, ministerial dedication. It was really an ideal environment for James Latta to obtain a fine education free of philosophical speculation and the looming and blooming influences of the New England theology.

In 1752, Dr. Alison became professor and vice provost of the College of Philadelphia which evolved to become the University of Pennsylvania. Given the Alison-Latta connection it is not surprising that James made his way to Philadelphia to continue at the feet of Common-Sense Alison who guided him so well that he delivered the Latin oration during graduation, May 17, 1757, when he received the A. B. (Bachelor of Arts). Tree years later his continued reading led to granting him the Master of Arts. As he persevered, he was hired a tutor and came under care of the Presbytery of Philadelphia as a candidate for the ministry. Candidates need intensive study of theology which Dr. Alison, of course, provided his protégé. February 15, 1758 was the date of Latta’s licensure so he could test his gifts for ministry, but he continued teaching at the college until he was sent with two other men by the Synod of New York and Philadelphia (reunited Old Side and New Side) to supply churches in another presbytery. Synod directed the men’s presbyteries to “take Care that these Gentlemen fulfill this Appointment, & neither prescribe nor show them Employment in our Bounds so as to disappoint this our good Intention” to “supply Hanover & other vacancies at the Direction of the Presbytery of Hanover” (Klett, 349). Thus ended his college teaching. The geographic bounds of Hanover Presbytery were on the ambiguous side because it included members in Virginia and the Carolinas “Settling to the Southward & Westward of Mr. Hogges Congregation” (298). The Presbyterians were flourishing in Quaker Pennsylvania while the Scotch Irish to the south and west struggled to establish congregations in Church of England controlled colonies. Ministers were reluctant to serve congregations on the frontier in territory where toleration of dissenters (i.e. Presbyterians, Congregationalists, Methodists, etc.) varied according to decisions by a bishop or the head of the Church of England, the reigning monarch.

About his work in Hanover Presbytery, Latta accepted a call from the Deep Run Church in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Deep Run was a Presbyterian settlement where Latta was installed minister of the village church in 1761. Just three years earlier the Old Side and New Side (not the same as the Old and New Schools) reunited following a division that began in 1741. The issues that contributed to separation included subscription to the Westminster Confession of Faith¸ itinerant and unqualified evangelists intruding on another man’s foundation (Romans 15:20), and the Log College’s perspective on experiential aspects of the faith. The Old Side pushed for full subscription, an end of invasive evangelists, and a balanced understanding of the place of experiential faith within the limits of sound doctrine; the New Side thought the Confession should not be subscribed to at all or subscribed to minimally, it continued using evangelists whether Presbyterian or not, and it pushed for a crisis of conversion for all who come to the faith. These three issues do not include all aspects of the division, but foundational to all points of discrepancy was doctrinal precision through full confessional subscription. The Log College in Neshaminy had closed with the passing of its founder, William Tennent, in 1746, but its perspective on theology continued with the founding of what became the College of New Jersey (Princeton University) that same year. Despite the reunion of 1758 not all ministers and churches were united doctrinally, and the variance was acute in the Presbytery of Philadelphia because it was greatly influenced by Log College men. For some with Old Side sympathies their theological differences were still great despite reunion but instead of separating again they managed to have a new presbytery erected within the bounds of the Presbytery of Philadelphia, May 28, 1762. The new Presbytery was within the same geographic bounds and made up of Old Side Presbyterians. The Old Side presbyters came up with the practical but uncreative name, Second Presbytery of Philadelphia (but note use of Old or New Side was avoided). Some of the ministers in the new presbytery included Latta’s mentor Francis Allison, along with John Thomson, John Ewing (a good friend of Latta), and Latta. The Deep Run Church was in the Scotch Irish tradition of the Old Side and James Latta shepherded it until he resigned in 1770.

A church in Chestnut Level in Lancaster County did not have a minister and Latta accepted its call and transferred to the Presbytery of New Castle May 16, 1771, but he was not installed until November. It was not a strong congregation because its membership was scattered on farms in the country and the one-hundred-pound salary could not provide Latta with freedom from worldly cares. It really did not matter what the salary was because he was rarely paid, so he put on his school-master’s hat and took on a few pupils to teach. Teaching went so well that enrollment increased necessitating contracting an assistant so Latta could dedicate more time to his congregation and less to his scholars. The school continued until closed for the Revolutionary War when Latta became a chaplain and many students joined the independence effort. It was not reopened until a few years after independence was achieved and continued to an undetermined date.

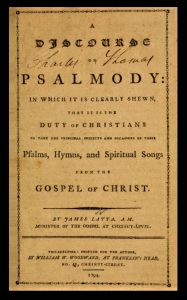

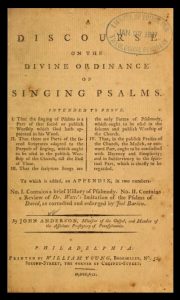

During his years at Chestnut Level use of the hymns and Psalms by Isaac Watts in worship services increasingly became an issue. Latta was an advocate of Watts but some of the prominent members of his congregation supported the exclusive use of Psalms. Latta eventually dropped the matter because he realized the older members of the church would have to die before any changes could be made. The abundant literature published about church worship music at the end of the eighteenth century is indicative of the controversy, but one proponent of exclusive Psalmody of particular importance was a minister in the Associate Church named John Anderson, who published A Discourse on the Divine Ordinance of Singing Psalms, 1791. The book states on the title page the four points he intended to prove, one of which is, “That the scripture songs are the only Forms of Psalmody, which ought to be used in the solemn and public Worship of the Church.” The other three points would likely have met with approval by Latta and others open to the work of Watts. Latta took on the challenge with A Discourse on Psalmody, 1794, in which he emphasized “Psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs” from Colossians 3:16-17 and the importance of worship music in the light of Christ’s incarnation and ministry. One source for support used by Latta is Thomas Ridgley’s A Body of Divinity, which is a four-volume collection of lectures on the Larger Catechism. In Ridgley’s discourse on Question 154 regarding the outward means of grace, he addressed worship and singing praise.

During his years at Chestnut Level use of the hymns and Psalms by Isaac Watts in worship services increasingly became an issue. Latta was an advocate of Watts but some of the prominent members of his congregation supported the exclusive use of Psalms. Latta eventually dropped the matter because he realized the older members of the church would have to die before any changes could be made. The abundant literature published about church worship music at the end of the eighteenth century is indicative of the controversy, but one proponent of exclusive Psalmody of particular importance was a minister in the Associate Church named John Anderson, who published A Discourse on the Divine Ordinance of Singing Psalms, 1791. The book states on the title page the four points he intended to prove, one of which is, “That the scripture songs are the only Forms of Psalmody, which ought to be used in the solemn and public Worship of the Church.” The other three points would likely have met with approval by Latta and others open to the work of Watts. Latta took on the challenge with A Discourse on Psalmody, 1794, in which he emphasized “Psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs” from Colossians 3:16-17 and the importance of worship music in the light of Christ’s incarnation and ministry. One source for support used by Latta is Thomas Ridgley’s A Body of Divinity, which is a four-volume collection of lectures on the Larger Catechism. In Ridgley’s discourse on Question 154 regarding the outward means of grace, he addressed worship and singing praise.

But if we have ground to conclude the composure, as to the matter thereof, and mode of expression, unexceptionable, and adapted to raise the affections, as well as excite suitable acts of faith in extolling the praises of God, it gives me no more disgust, though it be not in scripture-words, than praying or preaching do when the matter is agreeable thereunto. (Latta, xiii; Ridgley, 2:98).

According to Ridgley, singing a hymn written by a composer to praise God is no different than praying and preaching in worship in that all three elements involve interpretation of Scripture. If Scripture can be interpreted as God speaks through his pulpit prophet to his flock, and as he leads prayer, then why cannot the congregation sing hymns of human composition? In all three elements, proper worship strives for theological precision and accuracy, and surely no sermon, prayer, or hymn is perfect, but God uses the words of man to interpret his Word to man. Latta was an Old Side minister of the strictest sort holding to full subscription to the Westminster Standards, but he did not believe his confessional commitment conflicted with the hymns of Watts and other writers.

According to Ridgley, singing a hymn written by a composer to praise God is no different than praying and preaching in worship in that all three elements involve interpretation of Scripture. If Scripture can be interpreted as God speaks through his pulpit prophet to his flock, and as he leads prayer, then why cannot the congregation sing hymns of human composition? In all three elements, proper worship strives for theological precision and accuracy, and surely no sermon, prayer, or hymn is perfect, but God uses the words of man to interpret his Word to man. Latta was an Old Side minister of the strictest sort holding to full subscription to the Westminster Standards, but he did not believe his confessional commitment conflicted with the hymns of Watts and other writers.

Dr. Latta labored in the ministry until just a short time before his death. Riding to church one Lord’s Day with his daughter Mary he was thrown from their carriage onto his head and was stunned. They continued to church where he preached with some difficulty before returning home. He passed in and out of consciousness before entering a coma. James Latta, D.D., died January 29, 1801.

Pastor Latta was an industrious, dedicated, and honored minister throughout his life. It is believed his Doctor of Divinity was given by his alma mater in Philadelphia. When the Presbyterian General Assembly convened in Philadelphia in 1793, Latta was a commissioner from New Castle Presbytery and was elected moderator to succeed John King. When he returned to Philadelphia for the next assembly he preached his retiring moderator’s sermon from 1 Thessalonians 5:12-13 before stepping down from the podium for Alexander MacWorter to direct the meeting. Other than his book on worship music, his publications are limited to sermons for days of prayer, thanksgiving, and fasting and their titles show his interest in things political. Indicative of his connectional work is A Sermon Preached at a Meeting of a Committee of the Presbytery of Newcastle, and also at the Opening of the Presbytery, 1814.

Latta was survived by his wife and children. He had married a member of the Deep Run Church named Mary McCalla when he was roughly thirty years old. Mary’s brother had a son named William Latta McCalla who became a minister. She continued to live on the family farm at Chestnut Level until her death at the age of sixty five, February 22, 1810. The family was sizeable with ten children of which eight survived their parents. All four sons—Francis Alison, William, John Ewing (named for Latta’s friend), and James all became ministers; the four daughters were Mary, Margaret, Elizabeth, and Sarah.

Since no portrait of Latta was available, the following verbal description by an acquaintance will be helpful. “His personal appearance was not great—slightly stooping, he appeared rather below medium height—very spare of flesh, he always looked older than his years. There was in him a blending of cheerfulness and gravity rarely met with.” It is not a complementary picture bringing to mind dastardly images of Ebenezer Scrooge that I have seen. It is not clear if the following is an inscription on a lost gravestone, from a plaque in a church, or simply the transcription of a memorial from Latta’s documents. Copies of “ his literature extensive” may be lost to history.

In memory of

THE REV. DR. JAMES LATTA,

Who died 29th January 1801, in the 68th year of his age.

By his death, society has lost an invaluable member;

Religion one of its brightest ornaments, and most amiable examples.

His genius was masterly, and his literature extensive.

As a classical scholar, he was excelled by few.

His judgment was strong and penetrating;

His taste correct, his style nervous and elegant.

In the pulpit lie was a model.

In the judicatures of the Church, distinguished by his accuracy and precision

After a life devoted to his Master’s service.

He rested from his labours, lamented most by those who knew his worth.

Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord from henceforth.

Yea, saith the Spirit, that they may rest from their labours,

And their works do follow them.

Barry Waugh

Notes: The header image of an unknown church in an unknown location was used because a more relevant image could not be located. Biographical information was obtained from the entry written by Robert P. DuBois in volume 3 of William B. Sprague’s, Annals of the American Pulpit. James’s father’s name, James, was kindly provided by an interested reader January 2022 (see the Latta family genealogical site). DuBois was married to the daughter of John Ewing Latta, was assisted by Latta’s only surviving son, and he had access to personal papers left by him, which means the information is likely very good. DuBois was also the stated clerk of New Castle Presbytery, so he had access to its minutes. An example of the primary source information available to DuBois is the information about the graduations from the University of Pennsylvania were taken from the degree itself. John Anderson later published Vindiciae Cantus Dominici. In Two Parts: 1. A Discourse on the Duty of Singing the Book of Psalms in Solemn Worship. II. A Vindication of the Doctrine Taught in the Preceding Discourse. With an Appendix: Containing Essays and Observations on Various Subjects, Philadelphia, 1800; in the second part of this book Anderson addresses points by Latta. See the University of Delaware website history page for attribution of its founding to Francis Alison. Guy S. Klett, ed., Minutes of the Presbyterian Church in America 1706-1788, Philadelphia: Presbyterian Historical Society, 1976; this fine transcription from the manuscript original minutes has hampered accessibility due to shortcomings of the index.