As Sandy Finlayson informs readers his description of Thomas Chalmers as “the chief Scottish man” is borrowed from a letter written by Thomas Carlyle to William Hanna thanking him for a copy of the last volume of his biography of Chalmers. Essayist, historian, and social commentator Carlyle had turned from his Calvinistic upbringing to an ambiguous religion that could be described as transcendental or mystical and not atheism. Both men had common interest in improving social conditions resulting from industrialization, so this mutual concern may explain Carlyle’s respect for Chalmers. Carlyle’s perspective on social change was briefly expressed by him: “All reform except a moral one will prove unavailing,” but his method to that end was not the evangelical Calvinism of Thomas Chalmers who believed moral change resulted from lives transformed by Christ. In Chief Scottish Man, Evangelical Press, 2021, Westminster Theological Seminary Director of Library Services & Professor of Theological Bibliography Sandy Finlayson provides a succinct but full account of the life of Thomas Chalmers and his significance for founding the Free Church of Scotland.

As Sandy Finlayson informs readers his description of Thomas Chalmers as “the chief Scottish man” is borrowed from a letter written by Thomas Carlyle to William Hanna thanking him for a copy of the last volume of his biography of Chalmers. Essayist, historian, and social commentator Carlyle had turned from his Calvinistic upbringing to an ambiguous religion that could be described as transcendental or mystical and not atheism. Both men had common interest in improving social conditions resulting from industrialization, so this mutual concern may explain Carlyle’s respect for Chalmers. Carlyle’s perspective on social change was briefly expressed by him: “All reform except a moral one will prove unavailing,” but his method to that end was not the evangelical Calvinism of Thomas Chalmers who believed moral change resulted from lives transformed by Christ. In Chief Scottish Man, Evangelical Press, 2021, Westminster Theological Seminary Director of Library Services & Professor of Theological Bibliography Sandy Finlayson provides a succinct but full account of the life of Thomas Chalmers and his significance for founding the Free Church of Scotland.

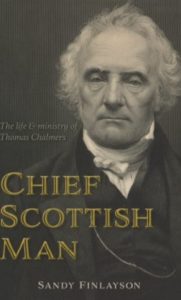

The book cover has a portrait of Chalmers and the first of four pictures in the book shows him as a young man. Other images present him as an elderly man, a preacher, and a presbyter who was moderator of the First General Assembly of the Free Church. Following an introduction, the first chapter explains the historical context, “Scotland in Transition,” then a series of chapters follow epochs such as his early life, each of three successive pastoral charges, teaching at St. Andrews University, “The Scottish Church Crisis 1828-1842,” “The Disruption,” and the Free Church. The last chapters assess Chalmers as a preacher and leader and as the “Chief Scottish Man.” A bibliography (thank you), endnotes, and index conclude the 171 pages of the book. The reviewer appreciates the book’s brevity and believes its concise and clearly written text make for informative reading not only by academics but also those who are less familiar with church historical biography.

During the years of Thomas Chalmers’s ministry, the Church of Scotland was divided between moderates and evangelicals. Moderates saw themselves as Scottish Enlightenment invigorated intellectuals whose religion was moral and of the decent sort, while the evangelicals (also decent) were Christians who believed the Bible is God’s word and they presented its gospel of grace with confessional commitment to the Westminster Standards. When the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland met in May 1843 the issue that came to debate between the moderates and evangelicals was patronage; moderates tended to support it and evangelicals tended not to. Patronage involved a laird, owner of a large estate, who selected and paid the minister for the local parish. The congregation had no say in selecting their minister until the Veto Act of 1834 gave the male heads of families the right to deny a patron’s appointment, but it was not all that effective in practice. Think about it. Would a farmer, shepherd, cooper, or even doctor or lawyer dependent on the laird for income vote to veto his appointee? One can see how such a system was not good for the church and was really nothing but a highly politicized form of episcopacy. Another aspect of patronage was some ministers sought pulpits funded by the wealthiest lairds because they could be set for life in a comfy parish if they minded their p’s and q’s. The debate ended dramatically when Thomas Chalmers and 202 other ministers and elders walked out of the General Assembly meeting in St. Andrew’s Church in Edinburgh. These men joined with others to become the Free Church.

One of the problems of The Disruption was a state church problem that had plagued Protestant churches since the king of Sweden confiscated church property and made his nation Lutheran in 1527. Funds for operating the Church of Scotland were obtained through pew fees paid by members of the congregation and the government oversaw how the funds were distributed. An example of the government’s influence is pointed out by Finlayson as he presented Chalmers’s effort during his Church of Scotland years to have more control over the congregational poor fund collection. Offerings would be collected in the parish only to have them re-distributed by the government to other parishes. The church and state concept at work in Scotland went back to John Knox who experienced Calvin’s Geneva and sought to adapt its church and government system for Scotland. Calvin saw both the church and state as servants of God with the former applying the Word and the latter wielding the sword, but his theory did not always make its way into practice in Geneva. There is not an iron wall of separation between church and state obstructing the influence of one upon the other, but instead the two ministries are bridged by their mutual responsibilities to God and respect for their individual duties. In Scotland, church and state were not mutual ministers but instead the church ministered subservient to the state. As state churches tend to be, the Church of Scotland was just another bureau of government weighed on the bookkeeper’s balance sheet and used for political gain.

Those who left with Chalmers to establish the Free Church paid a high price. Financially there was no more patronage for salaries which meant some ministers from poorer parishes found themselves in hard times. Finlayson notes that Chalmers and others of means contributed to alleviate the needs of their poorer brethren. The Church of Scotland churches where the ministers had preached were government property, so Free Church ministers and their congregations had to find places to gather for worship. Chalmers had hoped to resolve the patronage issue within the Church of Scotland and continue as one of its ministers with government support but instead a free church, something Chalmers reluctantly embraced, became a necessity. By nature, a free church was not only free of state church rule but also its funds.

This review has concentrated on The Disruption and the factors contributing to founding the Free Church, but Finlayson provides other information about the ministry of Thomas Chalmers and assesses him as a leader and preacher. He shows development in the preaching of Chalmers and exposes some of his weaknesses. He observed that during his earlier years of ministry Chalmers would select a Bible passage for his sermon text and then talk about something else, but this was not uncommon for sermons in the era. Despite the heritage of Puritan expository preaching enjoyed by Presbyterians, the principles have not always made their way into the methodology used by preachers. Finlayson also commented that even though Chalmers was a hard worker and capable leader, he could be moody and harsh in his interpersonal relationships, but the overall picture of Chalmers presented in Chief Scottish Man is one of considerable intellectual ability, dedicated pastoral concern especially for the poor, a lover of family, and an attentive churchman. The book is simple but not simplistic, clearly written, and provides not only the life of Chalmers but a good survey of ecclesiastical issues that occurred during his sixty-seven years of life in Scotland.

Barry Waugh

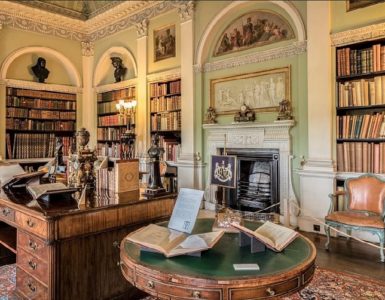

Notes: The header shows Edinburgh from the perspective of St. Anthony’s Chapel and it is dated 1831. Edinburgh Castle is on the left; note the smoke of industry coming from the stack near the center. The Carlyle quote in the first paragraph is from Critical and Miscellaneous Essays, vol. 4, New York: John W. Lovell Company, 143, as accessed on Internet Archive.