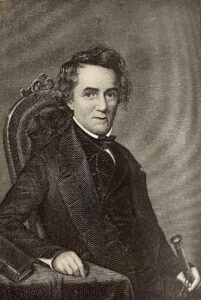

Philip was born December 21, 1786, to Isaac and Phebe (Condict) Lindsley at the residence of his maternal grandmother near Morristown, New Jersey. He prepared for college studying for three years in an academy under the direction of Rev. Robert Finley. Finley was a graduate of the College of New Jersey (Princeton) and was a tutor before ordination to the ministry. With the encouragement of Finley, Lindsley, just shy of his sixteenth birthday, entered the junior class at Princeton. Following graduation in 1804, he became a teacher in a school in Morristown, New Jersey, before returning home to teach with Finley. Lindsley professed faith in Christ and became a member of Finley’s church where he soon felt called to the ministry. After resigning from the school at Morristown he came under care of the Presbytery of New Brunswick and returned to the College of New Jersey for two years to teach Latin and Greek while studying theology primarily with Samuel Stanhope Smith. Continued studies earned Lindsley the A.M. in 1807. He was licensed to preach the gospel by presbytery April 24, 1810.

Philip was born December 21, 1786, to Isaac and Phebe (Condict) Lindsley at the residence of his maternal grandmother near Morristown, New Jersey. He prepared for college studying for three years in an academy under the direction of Rev. Robert Finley. Finley was a graduate of the College of New Jersey (Princeton) and was a tutor before ordination to the ministry. With the encouragement of Finley, Lindsley, just shy of his sixteenth birthday, entered the junior class at Princeton. Following graduation in 1804, he became a teacher in a school in Morristown, New Jersey, before returning home to teach with Finley. Lindsley professed faith in Christ and became a member of Finley’s church where he soon felt called to the ministry. After resigning from the school at Morristown he came under care of the Presbytery of New Brunswick and returned to the College of New Jersey for two years to teach Latin and Greek while studying theology primarily with Samuel Stanhope Smith. Continued studies earned Lindsley the A.M. in 1807. He was licensed to preach the gospel by presbytery April 24, 1810.

He tested his gifts for ministry for two years supplying various pulpits while studying at Princeton. Several congregations including the Presbyterian Church in Newtown, Long Island, found him a proficient preacher and offered calls, but he declined them all. In 1811 he was twice offered the presidency of Transylvania University in Kentucky but declined these opportunities as well. Following an extended trip through New England with Finley, he returned to Princeton to become senior tutor of languages in the college in 1812. The next year he was appointed professor of languages, was elected secretary of the Board of Trustees, and soon thereafter added to his duties were those of librarian and dean. Lindsley was important for the operation of the college, but more importantly, another aspect of his work may have helped the college survive.

The year Lindsley returned to Princeton was the beginning of the ten-year tenure of Ashbel Green, D.D., as college president. It was an era of student unrest, vandalism, lawsuits, and declining enrollment. One of Green’s duties was raising funds to sustain and improve the college, but as a board member of the Presbyterian Church’s newly opened and much anticipated seminary at Princeton, Green instead raised funds for seminarians rather than for the collegians that were his immediate responsibility. One historian of Princeton, Thomas J. Wertenbaker, is critical of the Green administration and the college board saying that,

In this period of retrogression, when the president and trustees seemed either blind to the needs of the college or incapable of meeting them—a larger endowment, more professorships, better teaching, better equipment, fresh intellectual springs [sources], national rather than denominational control, a saner policy in maintaining discipline—there was among the faculty members one of the most progressive and ablest educational thinkers in the country. Philip Lindsley, the son of an Englishman of a distinguished family, studied under Robert Finley, graduated from Princeton when eighteen, became a tutor in 1807, studied theology under Samuel Stanhope Smith, and in 1817 became vice-president of the college. Despite his sensitiveness and nervous temperament, he was an interesting teacher and profound scholar. Amidst all the tumults in Nassau Hall, all the harsh repressive measures of the faculty and trustees, the students always respected Lindsley as their friend and trusted adviser. (p. 162)

Was Lindsley recognized by the college leadership as a reliable liaison between the restless students and disconcerted faculty? It would seem so because when Elijah Slack left the college vice presidency in 1817, student-beloved Lindsley was appointed to his position. He was soon ordained, sine titulo (without call), by the Presbytery of New Brunswick. Lindsley continued as vice president until he became acting president when Green resigned in 1822. Even though the college wanted him to continue in the presidency, after refusing an offer to the presidency of Ohio University he accepted an offer from what was then Cumberland College in Tennessee. Cumberland College had been created by Congress in 1806 with its substance drawn from Davidson Academy (founded December 29, 1785). Lindsley was inaugurated January 12, 1825, then as he had requested the name was changed to the University of Nashville Nov. 27, 1826. Nashville and the newly named university were transitioning from their rugged frontier beginnings into important places for further westward expansion while the city would eventually come be known as “Athens of the South.”

The University of Nashville was to be Christian but non-sectarian possibly because of a significant problem facing Lindsley. According to Woolverton, there were too many denominational colleges competing for too few dollars, so the more generic religious designation could increase enrollment (p. 9). But with respect to the education itself, he would set the University of Nashville apart from the existing Old Southwest colleges by following a different curriculum model. Under his leadership, by 1837 courses would be offered in “ancient languages and literature, Oriental languages, history, mathematics, astronomy, chemistry, architecture, geology, archaeology, philosophy, law, political and economic statistics, fine arts, physiology, engineering, mechanics, and biblical literature” (Woolverton, pp. 19-20). To move the University of Nashville to its end Lindsey would present a new plan for education in his inaugural address.

Let us, then, borrow some ideas from the schools at Hofwyl and Yverdun—something from the ancient Greeks and Romans—something from our own Military Academies at Norwich and West Point—something from the pages of Locke, Milton, Tanaquil Faber, Knox, and other writers—something from old and existing institutions of whatever kind—something from common sense, from experience, from the character, circumstances and wants of our youth, from the peculiar genius of our political and religious institutions; and see whether a new gymnasium or seminary may not be established, combining the excellencies and rejecting the faults of all. I seriously submit it to my fellow citizens, whether this subject is not worthy of more than a passing thought or momentary approbation. Who is prepared to enter fully into its spirit, and to engage heart and hand in the enterprise? (pp. 99-100).

The schools at Hofwyl and Yverdun were founded by Swiss educators Phillip E. von Fellenberg and Johann H. Pestalozzi circa 1800 and when considered together offered in their curriculums learning by doing, classical education, education for the poor and middle class, self sustaining income from agriculture, and other innovations. The reason several colleges had wanted Lindsley for their president’s office is because his views were innovative and he was willing to consider options for improving curriculum. Likely, those at Princeton wanting him to stay had hoped his favor among students would enhance his presidency and would have taken the school in a new direction by modifying its classical-liberal curriculum with ideas such as those of Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767-1835) whose concepts led to establishment of the University of Berlin as the first research university in 1810.

During his years in Nashville one of Lindsey’s honors was serving as moderator of a General Assembly. The General Assembly convened in Seventh Presbyterian Church, Philadelphia, Thursday May 15, 1834 at 11:00. The retiring moderator, William A. McDowell, opened the sessions with a sermon from Psalm 122:6, “Pray for the peace of Jerusalem.” Philip Lindsley was unanimously elected moderator. A key decision made at the Assembly was indicative of increasing tensions regarding the Plan of Union and the relationship between the Presbyterians and Congregationalists. Committed to a committee of three was the following overture,

An application from the Synod of Ohio, requesting that the young men who are sent within their bounds as missionaries with a view to settlement, may have their ordination deferred until they come within their bounds. (Minutes, p. 425).

The committee’s report was adopted and reads as follows,

Whereas many of the ministers, who are to supply the vacant churches and destitute places in the more new and growing parts of our church must for some time to come, continue to be educated in the older sections of our country, and at a great distance from the field where they are to be employed; and whereas, it is important to the happy and useful settlement of these ministers in their several fields of labor, that they should enjoy the full confidence of the ministers and churches among whom they are to dwell; and whereas the ordination of ministers in the presence of the people among whom they are to labor is calculated to endear them very much to their flocks, while it gives their fathers and brethren in the ministry, an opportunity of knowing their opinions and sentiments on subjects of doctrine and discipline; and whereas our Form of Government seems to recognize the right and privilege of each Presbytery to examine and ordain those who come to the pastoral office within their bounds, and who have never before exercised that office. Therefore, Resolved, 1, That it be earnestly recommended to all our Presbyteries, not to ordain, sine titulo [without call], any men, who propose to pursue the work of their ministry in any sections of the country where a Presbytery is already organized, to which they may go as licentiates and receive ordination. 2. That the several bodies with which we are in friendly correspondence in the New England States, be respectfully requested to use their counsel and influence to prevent the ordination, by any of their Councils or Consociations, of men who propose to pursue the work of the ministry within the bounds of any Presbytery belonging to the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church; and that the Delegates from this Assembly to those bodies respectively be charged with communicating this resolution. (Minutes, p. 428)

With the overlap of the Congregationalists and Presbyterians in the western synods some presbyteries were ordaining ministers to work in presbyteries not within their bounds and building on the foundation of the other denomination. The Congregationalists were ordaining candidates to work in fields already served by Presbyterians. For example, a Presbyterian church might be established in a western village as a church or there might be indication of already present ministry such as a preaching point (temporary place for worship such as an orchard, livery stable, barn, etc.), but a Congregational missionary from the east, ordained in the east, would come and minister in the same place.

The Synod of West Tennessee submitted two overtures concerning baptism. The first asked “Is it expedient in the present state of the Church for a Presbyterian minister to baptize by immersion in any case?” The second inquired “Is the baptism of the children of non-professing parents to be regarded as valid baptism?” Both were committed to a committee of three commissioners. The Assembly adopted the committee’s reports which said,

The Confession of Faith, 28:3 says, “dipping of the person into water is not necessary; but baptism is rightly administered by pouring or sprinkling of water upon the person.” Your committee sees no cause for adding anything to the doctrine of the Confession on this subject.

The answer to the second question referred the Assembly to a decision in 1790 as found on pages 94-95 of A Digest Compiled from the Records of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church, 1820. The portion of the Digest addressing the question is as follows,

The following question was proposed by the committee of overtures: viz. Ought such persons to be re-baptized, as have been offered in baptism by notoriously profligate parents, and baptized by ministers of the same description? On this question the General Assembly, after a full investigation, adopted the following determination,

Resolved, That it is a principle of this church, that the unworthiness of the ministers of the gospel does not invalidate the ordinances of religion dispensed by them.—It is also a principle, that as long as any denomination of Christians is acknowledged by us a church of Christ, we ought to hold the ordinances dispensed by it as valid, notwithstanding the unworthiness of particular ministers. Yet, inasmuch as no general rule can be made to embrace all circumstances, there may be irregularities in particular administrations, by men not yet divested of their office either in this or in other churches, which may render them null and void.—But, as these irregularities must often result from circumstances and situations, that cannot be anticipated and pointed out in the rule, they must be left to be judged of by the prudence and wisdom of church sessions, and the higher judicatories to which they may be referred. In such cases, it may be advisable to administer the ordinance of baptism in a regular manner, where a prophane exhibition of the ceremony may have been attempted.—These cases and circumstances however are to be inquired into by the church sessions, and referred to a Presbytery before a final decision..

Another issue regarding baptism had been referred from the last Assembly. The question was whether Roman Catholic baptisms should be considered valid reported and were discharged from further duties. The report was not found in the minutes, but the Assembly likely referred the petitioners to previous actions regarding the same question..

These examples from the 1834 Assembly show the growing pains of the Presbyterian Church. The issues of an unworthy minister baptizing children of non-Christian parents, missionaries being ordained by entities not having direct authority over the candidates, and what was a reoccurring question coming from the presbyteries about the validity of Roman Catholic baptism all show concern for the urgency of missionary efforts within less than ideal circumstances. As Presbyterians moved west further into the land of the Louisiana Purchase, concerns about Catholic baptism would be more commonly encountered because of its French influences.

When the Assembly convened in First Church, Pittsburgh, the following year, Lindsley was unable to attend, so Samuel Miller delivered the sermon. His text was 2 Corinthians 4:7, But we have this treasure in earthen vessels, that the excellency of the power may be of God and not of us.

Philip Lindsley resigned the presidency of the University of Nashville in 1850, then moved to Indiana where he taught at Indiana Theological Seminary located in New Albany on the Ohio River. New Albany Seminary was struggling to continue as a Presbyterian seminary and it was hoped Lindsley could strengthen its situation. He returned to Nashville as a commissioner for his presbytery to attend the General Assembly and conveniently lodged with some family members. While there he suffered a stroke and died two days later, Friday, May 25, 1855. He was buried at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Nashville. Lindsley was married to Margaret Elizabeth Lawrence in 1813 who lived until December 5, 1845. Then in 1849 he married Mary Ann Ayers, a widow, and she survived him. He left five children, three sons and two daughters. As has been seen, Lindsley was honored as moderator of a general assembly, but he was also honored by election in 1837 to the Royal Society of Northern Antiquaries which was dedicated to the study of art, literature, language, and history of the Scandinavian nations. In 1823 he was given the Doctor of Divinity, D.D., by Dickinson College. An indication of the respect for him and popularity as a potential college president are the several other schools that sought his leadership, such as, Washington College, Lexington, Virginia; Dickinson in Carlisle, Pennsylvania; two from the University of Alabama; one to become provost of the University of Pennsylvania; the presidency of the College of Louisiana at Jackson; and South Alabama College at Marion.

Barry Waugh

For downloads of his writings, see the Log College Press website, Philip Lindsley (1786-1855).

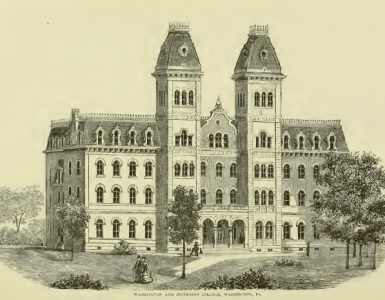

Notes—The header image was taken January 20, 2014 and is titled, “Nashville Children’s Museum, Lindsley Hall.jpg,” as from Wikimedia Commons. The building was completed in 1853 for the University of Nashville, is named to honor Philip Lindsley, and is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The book by Thomas J. Wertenbaker is Princeton University, 1746-1896, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1946. For more information about the tumultuous years of the Green presidency at Princeton, see Mark Noll, Princeton and the Republic: 1768-1822, Princeton University Press, 1989. The article by Sara Harwell, “Philip Lindsley,” from the online Tennessee Encyclopedia was used, as was, W. B. Sprague’s, Annals of the American Pulpit, vol. 4, 465ff. Information about the founding of Cumberland College is from the webpage of the “University of Tennessee Institute for Public Service,” “Private Acts Compilations,” “Board of Education,” “Acts of 1806, Chapter 7,” found HERE. Information about the University of Nashville is available in Laws of the University of Nashville, in Tennessee, Nashville: Printed by B. T. M’Kennie, Whig and Steam Press, 1840, and First annual announcement of the Medical Department of the University of Nashville, Nashville: J. T. S. Fall, Book and Job Printer, 1851. See also, John F. Woolverton, “Philip Lindsley and the Cause of Education in the Old Southwest,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 19 (March 1960), 3-22. Lindsley’s “Inaugural Address” is in The Works of Philip Lindsley, D.D., vol. 1, Educational Discourses, ed. Le Roy J. Halsey, Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Co., 1866; there are three volumes in the set. John F. Woolverton, “Philip Lindsley and the Cause of Education in the Old Southwest,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 19 (1960): 3-22. The edition of the General Assembly minutes used is, Minutes of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America from A.D. 1821 to A.D. 1837 Inclusive, Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication and Sabbath School Work, [1847]; 1834 minutes are on pages 418-461. James F. Davidson, “Philip Lindsley: The Teacher as Prophet,” Peabody Journal of Education, Vol. 41, No. 6 (May, 1964): 327-331. John E. Pomfret, “Philip Lindsley: Pioneer Educator in the Old Southwest,” in Willard Thorp, editor, The Lives of Eighteen from Princeton, Princeton: University Press, 1946, pages 158-77; also among the eighteen are Benjamin Rush, John Witherspoon, Samuel S. Smith, Henry Lee, James Madison, Charles Hodge, Woodrow Wilson, and F. Scott Fitzgerald.