John McKnight was born near Carlisle, Pennsylvania, October 1, 1754. His father was an officer in the colonial militia during the French and Indian War. John’s mother was left a widow when he was a boy, but she then remarried. Little is known of McKnight’s life until he entered the College of New Jersey (Princeton), where he graduated during the Presidency of John Witherspoon in 1773. Included among his thirty co-graduates were William Graham, Hugh Hodge (father of Charles), and Henry Lee, Jr. (“Light-Horse Harry,” father of General R. E.); two sons of Robert Smith who was the moderator of the First General Assembly of the PCUSA—John Blair Smith and William Richmond Smith; a son of Lower Marsh Creek Church, Samuel Waugh, became a country pastor; and the son of President Witherspoon, John, Jr., became a physician and surgeon. If the class had a reunion, the conversation must have been interesting with a variety of subjects. McKnight was a member of the American Whig Society and at commencement advocated in his graduation discourse, “Every human Art is not only consistent with true Religion, but receives its highest Improvement from it” (Princetonians). Shortly after completing college he went west in Pennsylvania to Shippensburg to study theology under the direction of pastor of the Middle Spring Church, Robert Cooper. He was licensed to preach about 1775 and ordained by the same presbytery.

After supplying several churches, McKnight’s first call was in Virginia organizing a church at Elk Branch which was located between the villages of Shepherdstown and Charleston (currently in West Virginia). He was ordained in December 1776 in a service directed by Hezekiah Balch and continued ministry there until 1782 when he resigned. Contributing to his decision to leave were his salary was severely in arrears and there was squabbling in the congregation about where worship services should be held. With several churches interested in him, he accepted a call to the Lower Marsh Creek Presbyterian Church back in Pennsylvania. Unlike some ministers in rural calls, McKnight received from Marsh Creek sufficient and timely salary payments amounting to £180 and 100 bushels of wheat a year. He was able to purchase a one-hundred-fifty-acre farm that was cultivated by the members of his church. The move from Elk Branch to Lower Marsh Creek was one from an unappreciative flock to one that loved him and his ministry. His years at Lower Marsh Creek were some of the most fulfilling of his pastoral ministry.

After laboring with Marsh Creek for about three years McKnight was called July 1789, to team with John Rodgers of the Collegiate Presbyterian Church in New York. The New York church wanted him to join in their work so much that Rodgers personally delivered the call to McKnight at Marsh Creek. It was a difficult decision given his fondness for farming and his congregation, but he accepted the call after considerable deliberation and encouragement from his presbytery. He was installed that December. The Collegiate Church had recovered under Rodgers’ leadership from a division over psalmody, and more recently the congregation had been divided over multiple candidates considered for the call that McKnight accepted. The two ministers worked together to unify the congregation with McKnight preaching three times on the Sabbath, lecturing on the Westminster Shorter Catechism during week-day evening gatherings, and working in private pastoral duties including frequent visitation. The collegiate church concept is a single congregation with multiple properties, which as McKnight entered the scene included two locations—Wall Street and Brick Church. The idea was, at least during the early years, that the ministers would rotate so that each preached at the properties on a regular basis, but this plan evolved into what one might expect as each location developed an affinity for a particular minister and the minister a location. Samuel Miller was ordained and installed a collegiate minister in 1793 to help McKnight because he was fatigued after a disease struck him the previous year. When Rutgers Street Church opened in 1798, Miller became its minister, and then John B. Romeyn was installed when Fifth Avenue Church opened in 1807. The four properties increasingly became separate congregations as their collegiate commitment declined, population density rose, and the geographical spread of properties increased. The building program for Rutgers Street incurred a considerable debt that was paid off thanks to efforts by McKnight. He worked hard but it came to the point where he believed his ministry was not appreciated and he thought Miller was clandestinely undermining his work with the flock. When the collegiate arrangement was ended and the churches became separate in 1809, McKnight believed he should have become minister of Wall Street, but the pulpit went to Miller. McKnight’s accusations against Miller were examined by the church and he was exonerated of any wrongdoing, but McKnight still was suspicious of Miller. After twenty years he had had enough of New York and its congestion, and he was soured about continued ministry in the city. His poor health combined with the feeling he was no longer needed contributed to his resignation and then the dissolution of his call in April 1809. When he left New York, it was a happy occasion because the considerable duties of city work combined with dissension concerning his ministry had left him bitter. He knew where he would go next.

John McKnight returned to the area of Pennsylvania where he was born settling in Chambersburg on a farm. Shortly after his relocation the Presbyterian Church of Rocky Spring—one of the oldest congregations in the region—unanimously called him to become its pastor. McKnight preferred serving as stated supply, so the congregation acquiesced. He enjoyed the work in the country call and relished in farming his land. Several congregations attempted to draw him back to New York, but he always said no. There is something to be said for waking up to quietness broken by the sounds of livestock on a sunny morning with ripe-unto-harvest fields in view, instead of arising to the smokey and dusty cacophony of a city with its crowds of people clanking up and down the streets. John McKnight thoroughly enjoyed his peaceful retirement living among a large circle of relatives and friends while ministering as stated supply. He served Rocky Creek until early in 1822 when he was stricken with an epidemic disease that left him bedridden for months before he died October 21, 1823. He was survived by his wife of forty-four years, Susan, who was the daughter of George Brown of Franklin County, Pennsylvania. The couple had ten children.

John McKnight was honored several times during his year short of three-score-and-ten years of life (see Psalm 90:10). In 1783 he was selected a charter member of Dickinson College’s board of trustees. Princeton granted him the A.M. in 1786, and in 1791, he was honored with the Doctor of Divinity by Yale. At Columbia College in New York he was a trustee 1793-1795, and professor of moral philosophy 1795-1799. In 1795, he was moderator of the General Assembly of the PCUSA when it assembled in Carlisle, and the following year he delivered his moderator’s sermon from 2 Corinthians 4:5, “For we preach not ourselves, but Christ Jesus the Lord, and ourselves your servants for Jesus’ sake.”

He was a visionary proponent of the PCUSA working harder to expand the denomination into the western areas of the nation and even promoted Chambersburg for the site of the denominational seminary before it was settled in Princeton. One point of disagreement with Samuel Miller had been political with McKnight having republican sympathies (common in the Carlisle region) while Miller held federalist views. McKnight saw the importance of expanding westward and decentralizing the federalist hub of the denomination in Philadelphia, New Jersey, and New York. McKnight’s publications were limited to single sermons or lectures in pamphlets, a collection of sermons on the subject of faith, and the memorial discourse he delivered when Dr. John King died. In 1815, he was president pro-tem of Dickinson College with the expectation he would continue in the office but just over a year later he resigned due to the dismal financial circumstances; he, with others, had hoped Dickinson would become the western Princeton College and extend the Presbyterians into the frontier. The federal structure of the denomination would not give up its authority to neither West nor South. John McKnight was happier on the farm with livestock and grain, and with the harvest of souls from Rocky Spring Church.

Barry Waugh

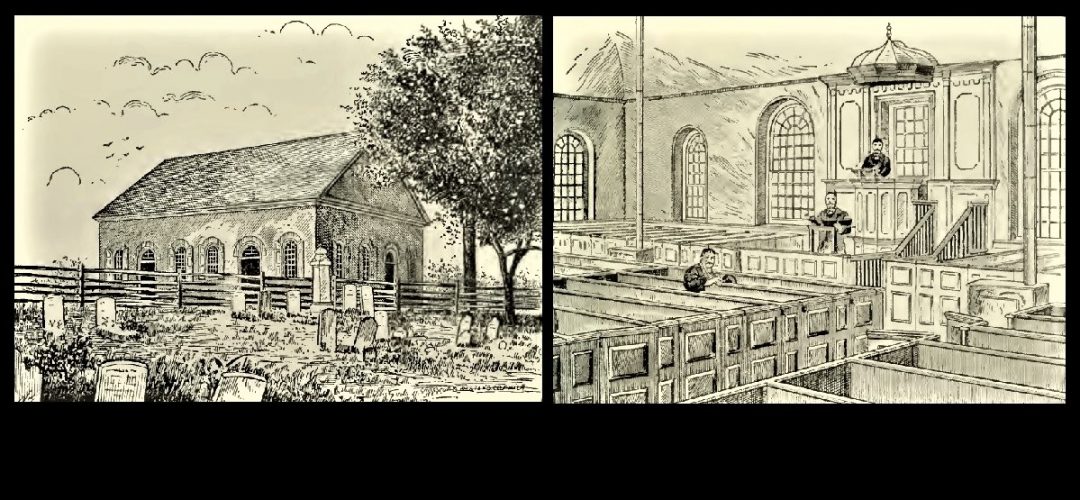

The sources for this biography are similar to those for other personalities of the period. Sprague’s Annals of the American Pulpit, vol. 3, 1858, provides the source material for biographies in later years including Alfred Nevin’s Men of Mark of the Cumberland Valley, 1876, and his Encyclopedia of the Presbyterian Church, 1884; also, the two volumes of Centennial Memorial of the Presbytery of Carlisle, 1889, use Sprague but they add material from judicatory sources as well as personal anecdotes (the header composite of the Rocky Spring Church is from images in vol. 1). For the best biography see Richard A. Harrison’s in Princetonians 1769-1775, Princeton University Press, 1980, which includes considerable new material from primary sources and a black and white portrait; several details from Harrison’s work were used in my biography. Shepherd Knapp’s A History of the Brick Presbyterian Church in the City of New York, 1909, has 700 pages of history and discusses the collegiate arrangement.