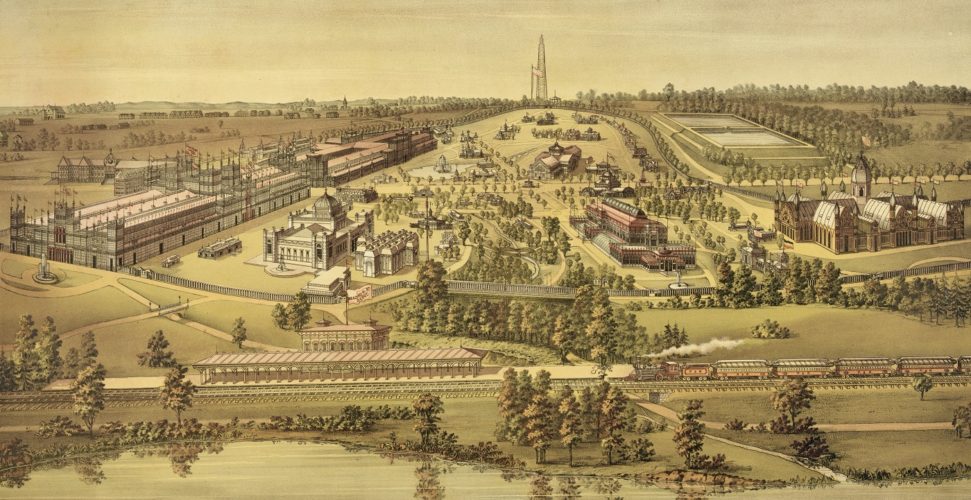

The International Exhibition of Arts, Manufactures and Products of the Soil and Mine was held in 1876 to commemorate achieving American independence one hundred years earlier. Fortunately, it has come to be known more briefly as the Centennial Exposition or Philadelphia Centennial, but for this post simply Centennial will be used. The Centennial was a massive project with 200 buildings constructed on 286 acres of Fairmount Park along the Schuylkill River. The grand opening was planned for April to commemorate the battles of Lexington and Concord but logistics problems combined with construction delays pushed the opening to May 10 with the gates scheduled to close permanently November 10. It was a massive, expensive, no holds barred world’s fair declaring that after just a century the United States of America was officially a world player and everyone should stand up, take notice, and expect great things. The Centennial promoted all things American including machinery, metals, mining, horticulture, agriculture, art, music, national resources, science, cuisine, and the aesthetic beauty of the varied terrain of the nation. An example of the impressiveness of the Centennial was the Corliss engine that powered over 800 machines through a complex labyrinthine network of belts, cogs, and shafts. The engine’s two forty-four-inch diameter pistons were driven through strokes of ten feet by the external-combustion energy provided by steam. Everything was intended to be the biggest and the best in the world as exemplified architecturally by the Main Exhibition Building which measured 1880 by 464 feet yielding over 870,000 square feet of floor space for exhibits. The event was not only national but international because other nations provided exhibits as birthday gifts for the country. Everything was done in a big way because the United States was proud of its accomplishments and optimistic about its future.

If and how were the Presbyterians going to have a part in the celebration of a century of the United States?

Historically, Presbyterianism had contributed to the progress of the United States via three key influences. First, politically, because the pattern for representative government of the United States followed that of presbyterian polity; second, educationally, since many schools and colleges in the land were started by Presbyterians; and third, religiously, inasmuch as the predominant Protestant Christian influence in the mid-Atlantic and southern states was from Presbyterians.

The question of partcipating in the Centennial came before the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA) in 1872. With much enthusiasm the commissioners appointed the Centennial Committee which included thirteen members—possibly intended to honor the thirteen original colonies. The Committee was to “take this subject into consideration, and make a report thereon to the next General Assembly.” The members included twelve men from the Philadelphia area: William P. Breed, Henry A. Boardman, Stephen W. Dana, George Hale, Addison Henry, George Junkin (see Notes), George Musgrave, Alfred Nevin, William A. Porter, William E. Schenck, and J. Ross Snowden, with a lone representative from Pittsburgh named Alexander W. Sproull. When the recommendations of the Centennial Committee were adopted the next year they included setting up a display of Presbyterian Board of Publication books and church artifacts at the Centennial; taking a collection for building a fire-proof facility for the Presbyterian Historical Society; offering a series of historical discourses on eras of Presbyterian history; dedicating the first Sabbath in July 1876 to be “a Day of Praise and Thanksgiving to God for the manifold blessings with which he has crowned us as a people”; and finally, inviting “other branches of the Presbyterian Church in the nation to cooperate with us in this work in so far, and in such manner, as they may deem expedient.” The Centennial Committee was aided in its efforts by addition of a sub-committee charged with finding speakers for historical discourses. When the Assembly convened in Cleveland in 1875, the Centennial Committee report had an addition tacked on its end. It was an important addition and as the years have passed the tacked-on afterthought is probably the most enduring aspect of the Centennial for Presbyterians. A statue was to be cast honoring Presbyterian Scottish-American John Witherspoon. Even though the Centennial Committee did not mention its reasoning for selecting Witherspoon, he was surely the ideal person to cast in bronze because he embodied all three of the influences provided by the Presbyterian Church in American history–political, educational, and religious.

The question of partcipating in the Centennial came before the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA) in 1872. With much enthusiasm the commissioners appointed the Centennial Committee which included thirteen members—possibly intended to honor the thirteen original colonies. The Committee was to “take this subject into consideration, and make a report thereon to the next General Assembly.” The members included twelve men from the Philadelphia area: William P. Breed, Henry A. Boardman, Stephen W. Dana, George Hale, Addison Henry, George Junkin (see Notes), George Musgrave, Alfred Nevin, William A. Porter, William E. Schenck, and J. Ross Snowden, with a lone representative from Pittsburgh named Alexander W. Sproull. When the recommendations of the Centennial Committee were adopted the next year they included setting up a display of Presbyterian Board of Publication books and church artifacts at the Centennial; taking a collection for building a fire-proof facility for the Presbyterian Historical Society; offering a series of historical discourses on eras of Presbyterian history; dedicating the first Sabbath in July 1876 to be “a Day of Praise and Thanksgiving to God for the manifold blessings with which he has crowned us as a people”; and finally, inviting “other branches of the Presbyterian Church in the nation to cooperate with us in this work in so far, and in such manner, as they may deem expedient.” The Centennial Committee was aided in its efforts by addition of a sub-committee charged with finding speakers for historical discourses. When the Assembly convened in Cleveland in 1875, the Centennial Committee report had an addition tacked on its end. It was an important addition and as the years have passed the tacked-on afterthought is probably the most enduring aspect of the Centennial for Presbyterians. A statue was to be cast honoring Presbyterian Scottish-American John Witherspoon. Even though the Centennial Committee did not mention its reasoning for selecting Witherspoon, he was surely the ideal person to cast in bronze because he embodied all three of the influences provided by the Presbyterian Church in American history–political, educational, and religious.

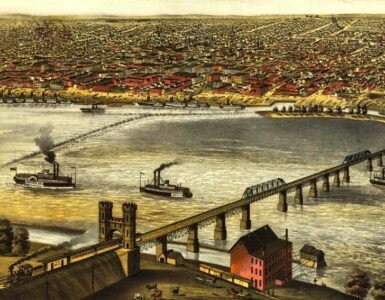

The cornerstone setting ceremony for the grand pedestal upon which the Witherspoon statue would be mounted was held Tuesday, November 16, 1875. The cornerstone was to be set upon the recently completed sturdy foundation. Complicating the ceremony was the mass of workers busily trying to get their jobs done so the Centennial could open on time. Also, as the celebration day wore on, the weather became increasingly worse. Those who could not abide the wet and cold were encouraged to go to Machinery Hall and await conclusion of the cornerstone setting process when Dr. William Adams would deliver a discourse to the attendees. Those braving the weather sadly could not appreciate the spectacular site that the sculptor, Joseph A. Bailly, had selected. It was strategically located in a corner of the Centennial’s grounds at a height sufficient to provide a fine view of the Schuylkill River, its steamboat landing, and the near-by Reading Railroad Exposition Station. With the cornerstone set, things were going well in terms of the schedule and once the pedestal was finished, the bronze of Witherspoon could be set in place.

The cornerstone setting ceremony for the grand pedestal upon which the Witherspoon statue would be mounted was held Tuesday, November 16, 1875. The cornerstone was to be set upon the recently completed sturdy foundation. Complicating the ceremony was the mass of workers busily trying to get their jobs done so the Centennial could open on time. Also, as the celebration day wore on, the weather became increasingly worse. Those who could not abide the wet and cold were encouraged to go to Machinery Hall and await conclusion of the cornerstone setting process when Dr. William Adams would deliver a discourse to the attendees. Those braving the weather sadly could not appreciate the spectacular site that the sculptor, Joseph A. Bailly, had selected. It was strategically located in a corner of the Centennial’s grounds at a height sufficient to provide a fine view of the Schuylkill River, its steamboat landing, and the near-by Reading Railroad Exposition Station. With the cornerstone set, things were going well in terms of the schedule and once the pedestal was finished, the bronze of Witherspoon could be set in place.

Progress on the bronze statue was slow. Bailly announced to the Centennial Committee that the model for the statue was completed in June 1875 and it had been hauled to Robert Wood & Sons Foundry for the bronze casting process. The statue was completed February 1, 1876, then it was placed on display at the foundry awaiting installation on the Centennial grounds. There was plenty of time to set the Witherspoon monument before its planned unveiling during the PCUSA General Assembly convening in Brooklyn at the Tabernacle Presbyterian Church on May 18. There were three and a half months to get the job done, but the deadline was not met. Frank L. Thomas, a young man of seventeen, commented in his diary recording a trip to the Centennial that he walked past the foundry on July 13,

and saw the statue of Rev. John Witherspoon one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence which is to be placed in Fairmount Park. (see Notes below)

The placement of the statue was already more than two months late. If commissioners to the Brooklyn Assembly in fact saw the bronze, they would have viewed it in the foundry. What happened?

The Witherspoon statue project was dogged by money problems from the beginning. Bailly had taken the commission for the statue without any money up front and only a promise from the Centennial Committee that “they would do all in their power to secure the money to remunerate him for his work.” The month before young Frank Thomas’s viewing of Witherspoon in bronze, the Presbyterian ladies were asked by the Centennial Committee to raise three-thousand dollars, which was quite a tidy sum in the day. When the statue eventually was unveiled future Princeton Seminary professor William M. Paxton would comment that the “ladies of the auxiliary set to work with characteristic energy” and “Witherspoon stands upon his pedestal owing no man anything” (Breed, 45). Note the exegetically questionable play on words from Romans 13:8 as Paxton pointed out that women had accomplished the job instead of the men. Whether the statue could not be moved because Robert Wood & Sons had not been paid, or the riggers hired to move Witherspoon required funds up front and none were available is not clear, but regardless, the women were able to raise the money.

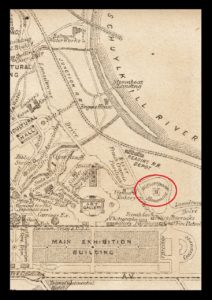

There were several editions of maps and guidebooks published for visitors to the Centennial and a comparison of their contents shows confusion about the Witherspoon statue. In some guides and maps, the site is not marked or noted at all, while others locate the site and its access road but the statue is not noted, but still others have the statue in its proper position. One map even has what appears to be a concession stand in the place of the bronze statue. Once the statue of John Witherspoon was placed, it was time for it to be unveiled and dedicated.

It was Monday, November 20, 1876, ten days aftern the Centennial closed for good when the unveiling of the statue occurred. William M. Paxton, minister of First Church, New York, as part of the unveiling ceremony read the inscriptions on each of the four sides of the statue’s pedestal (see Breed).

On the east side: “John Witherspoon, D.D., LL.D., a lineal descendant of John Knox, born in Scotland February 5, 1722; ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church, 1745; president of the College of New Jersey, 1768-1794. The only clergyman in the Continental Congress; a signer of the Declaration of Independence; died at Princeton, N. J., November 15, 1794.”

On the west side: “This statue is erected under the authority of a committee appointed by the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, July 4, 1876.”

On the south side: “Proclaim liberty throughout all the land, unto all the inhabitants thereof. Lev. 20:10.” [The verse inscribed on the Liberty Bell.]

On the north side: “For my own part, of property I have some, of reputation more; that reputation is staked, that property is pledged, on the issue of this contest. And although these gray hairs must soon descend into the sepulcher, I would infinitely rather that they should descend thither by the hand of the executioner than desert at this crisis the sacred cause of my country.—Dr. Witherspoon.”

Just as Dr. Paxton pronounced the word country at the end of the Witherspoon quote, the Honorable D. W. Woods of Lewistown, Pennsylvania, a grandson of Dr. Witherspoon, pulled a cord, resulting in the flag that was covering the bronze falling to expose the nearly thirteen feet of the John Witherspoon bronze. A thrill of surprise and admiration ran throughout the crowd. Paxton was for the moment forgotten as shouts and applause filled the air. When quiet was restored, Dr. Paxton proceeded as follows:

That monument may perish, but this sentiment (of Witherspoon’s) will live forever. As the reward for his signature to the Declaration of Independence he expected the executioner’s axe, but instead of this he has found the sculptor’s chisel. He staked his reputation upon the issue of that crisis and has won immortality. He staked his property, and he himself has become the property of his countrymen.

It was good that the Presbyterians embraced the opportunity to participate in the Centennial. Only two of the Centennial ‘s 200 buildings remain today—the current Please Touch Museum, originally Memorial Hall, and the present Centennial Café, originally Ohio House. One would have expected more buildings to remain. But there is another survivor because John Witherspoon has been standing on his pedestal 150 years this year. The bronze Scottish-American with his Geneva gown draped over his arm symbolizing his ministerial calling stands more than twice-life size upon his pedestal. The panorama before him has changed from horses and carriages passing on a path, to horseless carriages on gravel, then to modern automobiles on asphalt. He now gazes at utility lines and a crooked wooden sign warning visitors not to park on the grass. The Schuylkill River cannot be seen from the statue’s promontory anymore because of thick trees backed by Interstate 76 (note the historical significance of using the number 76 in Philadelphia). Even though the statue’s scenic original site is not what it used to be, John Witherspoon continues to stand as first of all, a minister of the Gospel; second, a Scot-American patriot; and third, a dedicated educator.

John Witherspoon is arguably the most important Presbyterian in American History. There is not much of significance in his era that he did not influence in some measure. When the PCUSA held its first General Assembly in 1789, Witherspoon was honored with calling the gathering to order as convener, but because of declining health and fading vision he yielded the gavel to John Rodgers of New York to continue the assembly. If Witherspoon were to pay a visit to the nation today, what would he think of the religious, political, and educational situation in the land for which he risked his life?

Barry Waugh

This article was first posted May 22, 2020 and it has been revised for posting in 2026 for the 250th anniversary of the United States and for the aforementioned 150th anniversary of the Witherspoon statue.

Notes—You may want to read the post, “John Witherspoon, Lecture Life and Works,” which includes William S. Plumer’s discourse on Witherspoon delivered in October 1876. The color header image is from Wikimedia Commons “Bird’s Eye View, Centennial Buildings, 1876.” The Witherspoon statue would be off the image to the left. The large structure on the left is the Main Building which was described in the first paragraph of this article. In the foreground is the landing for steamboats. The train is approaching the Reading Railroad Exposition Depot. If you would like to see the statue as currently in situ, search on the world’s largest map site the words, John Witherspoon Statue Fairmount Park Philadelphia, and take a virtual walk to see it. For information about two Witherspoon statues that are identical, one in Scotland and the other in Princeton, see on this site, “John Witherspoon, 1723-1794.” There is also a statue of Witherspoon on the grounds of the Presbyterian Historical Society, 425 Lombard Street, in Philadelphia. At one time the PHS was in the Witherspoon building. The PCUSA General Assembly minutes, 1872-1877, were an important source and text in this post given in quotes came from these sources, however a summary was published in William P. Breed’s, Witherspoon: Proceedings and Addresses at the Laying of the Corner-Stone and at the Unveiling of the Statue of John Witherspoon, in Fairmount Park, Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1877. Information about the buildings and property of the Centennial were obtained from “What Happened to the Buildings from the 1876 Centennial in Fairmount Park?” on The Philadelphia Inquirer website, and from Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, ed. Russell F. Weigley, New York: W. W. Norton, 1982. The map section of the Exhibition is from, https://digital.library.cornell.edu/. The description of the current Witherspoon statue situation is based on using the street view of an online mapping site, May 18, 2020. The George Junkin on the Assembly’s Centennial Committee was the son of the George Junkin having a biography on this site. The italicized quote is from page 3 of young Thomas’s diary, which measures 3 1/2″ x 5″, has 32 pages, and covers the trip from July 12 to 26, 1876. The handwriting is quite legible. It is held by the Free Library of Philadelphia and can be viewed online. It might make a nice source for a school or home school student paper, but of course, those students encumbered with not having been taught cursive writing would, sadly, find the diary challenging if not impossible reading. The address for the color picture of the Witherspoon statue is—https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Witherspoon_Hort_Center.JPG.