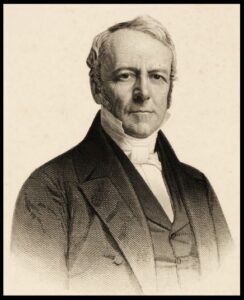

James Waddell was born to Archibald and Janetta (Waddell) Alexander in Louisa County, Virginia, March 13, 1804. His ancestry provided direction for who he would become. He was named for his mother’s father, James Waddell, a native of Ireland who grew up in southeastern Pennsylvania and was schooled by Samuel Finley at Nottingham. Waddell was ordained by the Presbytery of Hanover and for much of his forty-years ministry served churches in the Shenandoah Valley and in later life lost his vision from cataracts. However, James Waddell continued to prepare sermons with the help of family members earning him the designation “The Blind Preacher of Virginia.” James’s father Archibald Alexander was from the Shenandoah Valley and ministered in Virginia and Philadelphia before becoming the organizing professor of the Presbyterian theological seminary at Princeton, New Jersey, 1812. If there is such a thing as having ministry in the blood, surely wee James had sanctified DNA from both parents.

James Waddell was born to Archibald and Janetta (Waddell) Alexander in Louisa County, Virginia, March 13, 1804. His ancestry provided direction for who he would become. He was named for his mother’s father, James Waddell, a native of Ireland who grew up in southeastern Pennsylvania and was schooled by Samuel Finley at Nottingham. Waddell was ordained by the Presbytery of Hanover and for much of his forty-years ministry served churches in the Shenandoah Valley and in later life lost his vision from cataracts. However, James Waddell continued to prepare sermons with the help of family members earning him the designation “The Blind Preacher of Virginia.” James’s father Archibald Alexander was from the Shenandoah Valley and ministered in Virginia and Philadelphia before becoming the organizing professor of the Presbyterian theological seminary at Princeton, New Jersey, 1812. If there is such a thing as having ministry in the blood, surely wee James had sanctified DNA from both parents.

After completing studies at the college in Princeton in 1820, he attended Princeton Seminary but did not complete the program, he instead studied about two years ending in 1824. Surely his failure to complete all the required classes was more than made up for by family chats with his founding professor father. From 1824 to 1825 he was a tutor at the college. His first ministry following ordination by Hanover Presbytery was in the Presbyterian Church, Charlotte Court House, Virginia, which began with a term as the stated supply and continued with a brief tenure as the installed pastor. He moved to Trenton, New Jersey, to serve the Presbyterian church, 1829-1832, then was editor of The Presbyterian, 1832-1833. His longest single service was as the Professor of Rhetoric and Latin Language and Literature in the College of New Jersey, 1833-1844.

Because of a renewed desire for pastoral ministry, he accepted a call in 1844 to the Duane Street Church in New York City which ended in 1849. Upon leaving New York he returned to Princeton to serve briefly as the Professor of Ecclesiastical History and Church Government in the seminary. However, he yearned to serve a congregation again, so he accepted a call that took him back to New York to become minister of the Fifth Avenue and Nineteenth Street Church. Hoping to relieve an illness, Dr. Alexander was granted leave from his church to rest and recuperate in Red Sweet Springs, Virginia, but he died, July 31, 1859, at the age of only fifty-five years. His body was returned to Princeton and buried near his father. James Waddell Alexander was honored during his lifetime with the Doctor of Divinity (D.D.) by both Lafayette College in Pennsylvania, 1843, and Harvard University, 1854. See the newspaper report about Alexander’s funeral at the end of this post.

Twenty-five years after J. W. Alexander’s death, the alumni of Princeton Seminary erected the Alexander Tablet in the campus chapel as a memorial to Archibald, James Waddell, and Joseph Addison Alexander for their ministries not only to the seminary but also the church in general. James Alexander was remembered at the service with a brief message presented by Theodore L. Cuyler, D.D., who was taught by Alexander during his teaching years at the College of New Jersey. Cuyler commented that Dr. Alexander was a prolific writer but he personally rated most highly “his Charles Quill letters to workingmen—which have the simplicity and pith of Benjamin Franklin” (p. 23). The Charles Quill letters had been published with the pseudonym as a series in the Newark Daily Advertiser before publication in a two volume set. The first volume is titled The American Mechanic, 1838, and the second one was published in 1839 as The Working Man. The books were republished in a set in 1847 bearing the single title, The American Mechanic and Working Man. Alexander commented that he was motivated to write the articles because he was greatly concerned about the challenges Americans faced as many moved from the rural areas for jobs in the factories of the rapidly growing and densely populated cities (The Life of J. W. Alexander, 1:145-46, 246, 266). Alexander thought like some of his contemporaries such as Robert L. Dabney that even though industrialization was bringing economic benefits and employment, it was also affecting the employees negatively with respect to their spiritual, family, and social lives.

The American Mechanic and Working Man might prove to be useful tools for home schooling and Christian schools. Though some aspects of the books are dated, Alexander tells several personal stories that illustrate the principles he presented in the volumes that might interest children. An advantage of this type of antiquarian book is that it not only gives wisdom for living, but also vocabulary, trades, and cultural aspects that could be incorporated in the teaching of history. Professions such as the cooper, tanner, weaver, joiner, and turner for the most part have either become specialized interests appealing to few or they have changed greatly due to technological innovations. It would be good for children to see how much time was involved in accomplishing trades and professions in the past in our age high-speed manufacturing and instant communication.

Additional information about Alexander can be found on this site in the articles, “The Student Woes of J. W. Alexander” and “J. W. Alexander’s Concern for the Poor.” The collection at Log College Press has PDF copies of his works available for free download. He may be the most prolific writer during the antebellum era of Princeton Seminary. He wrote general and church history volumes; books for children; works for instruction in preaching; books about systematic theology subjects; numerous reviews including one of a book about Hegel; titles about family devotional practices; a life of David’s son Absalom; an interesting titled book, Good–Better–Best; or, The Three Ways of Making a Happy World; books about studying the Bible; one textbook about The Life of Jacob and His Son Joseph; one book about Hebrew customs; and several other titles.

A recent study of an aspect of Alexander’s life and ministry is Gary L. Steward’s Th.M. thesis for Westminster Theological Seminary, Philadelphia, titled, “James W. Alexander’s Christian Social Reform in its Antebellum American Context,” 2010. He has also published the article, “Old Princeton and American Culture: Insights from J. W. Alexander,” in The Confessional Presbyterian 8 (2012), pages 55-64. In his 183 page thesis inluding the bibliography, the chapters address Alexander as a pastor and social reformer; politics and the structure of society; utopian socialism; abolitionism; and secularized education.

Barry Waugh

The following account of Alexander’s funeral is from the Old School newspaper The Central Presbyterian, August 20, 1859, page 2. The paper was published in Richmond, Virginia, and was owned and edited by Moses D. Hoge and T. V. Moore.

FUNERAL OF DR. ALEXANDER

Our Northern Exchanges bring a full account of the solemn and impressive services which preceded the burial of Dr. Alexander. We are sure that our readers will read with deep and mournful interest the following account of the obsequies. The Philadelphia newspaper, the Presbyterian [Old School], says:

The funeral services of the deeply lamented Rev. Dr. James W. Alexander were held in the First Presbyterian Church, Princeton, New Jersey, on Wednesday September 3.

In the pulpit were the Rev. Drs. [Charles] Hodge, [David] Magie of Elizabeth, New Jersey, Thompson of New York, and Professor [Matthw B.] Hope of the College; whilst in the front pew were the five remaining brothers—the Rev. Dr. J. Addison Alexander, the Hon. William C. Alexander, Archibald Alexander, M.D., the Rev. Samuel C. Alexander, and Henry M. Alexander, Esq. The services were commenced with the hymn,

“Hear What the Voice from Heaven Proclaims”

[Isaac Watts]

“The Rev. Dr. Thompson then read a portion of Scripture, which was followed by a prayer by the Rev. Dr. Magie. The sermon was by the Rev. Dr. Hodge, whose heart was overflowing with sorrow, and whose words were what might have been expected from this eminent man of God on the death of one he so much honored and so dearly loved. The text was Matthew 25:34,

Come, ye blessed of my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world.

It seems almost impossible that the place made vacant by his decease can ever be filled again in the manner in which it previously was. Dr. Alexander united gifts and graces rarely combined in one man. He had a great memory, powerful intellect, and application, these gifts being greatly cultivated. Probably no one in the Church was a better scholar—understanding the French, Spanish, Italian, and German, not only as languages but as vehicles for conveying knowledge. His style was brilliant, resembling Macaulay [author, “The History of England,” seventeenth century] in some respects—many of his productions being like strings of pearls, each perfect in itself, and yet bound together by an invisible thread. He once said the only trouble he had in writing was turning the leaves.

The Princeton Review was indebted to him for many of its ablest articles. He also wrote a great number of books of a religious character. As a theologian, he was erudite, and as theology and philosophy are intimately connected, he was well versed in each. These were some of his gifts, but the greatest to be marked was the man, the Christian, the Israelite in whom there was no guile [Jesus speaking with reference to Nathaniel, John 1:47]. Free from hypocrisy and malice, no one ever heard of him saying an unkind thing; but things pure, lovely, and of good report [Philippians 4:8]. No one can think of him without being better.

Being brought early under the influence of Christianity, he was full of faith and the Holy Ghost [alluding to Barnabas, Acts 11:24]. The pulpit was his favorite place, where he reproduced scriptural pictures in a manner that seemed to bring them to life again—where vivacity of thought and fertility of illustration characterized him. He endeavored to lead men away from themselves and direct them to Christ. The great charm of his preaching was power over the religious affections—reverence, joy, contrition, and gratitude, which he could call up at pleasure. Prayers which he offered were real acts of thanksgiving and supplication. Dr. Alexander’s pre-eminence was not owing to any one faculty, but to a combination of parts, and this led so many to sit under his preaching from year to year with so much interest.

Frequent family affliction and nervous suffering made him a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief [Isaiah 53:3], and when he entered heaven it may be said, “This is one that has come out of tribulation” [Revelation 7:14]. But we must not consider selfishly our own loss. Through a long life of usefulness, he was the admiration of thousands here and now there is laid up for him a crown of righteousness [2 Timothy 4:8]. Who would not rather have been and now be in his place, than that of the greatest warrior or statesman that ever lived? The great lesson taught us here is that Christ is the Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end, the first and the last [Revelation 22:13], who has redeemed us by his precious blood.

At the conclusion of the discourse the congregation joined in singing the hymn,

“O For the death of those,

Who slumber in the Lord!”

[“The Peaceful Death of the Righteous,” James Montgomery]

after which the mournful procession moved to the burial-ground, and the cherished remains were laid in that dust where were already sleeping so many of the illustrious dead. A memorable day was this in the necrology of Princeton. Deep was the grief of that mourning group as they realized that on earth they were to see that face no more.

The New York Observer [New School] speaks of another group of mourners at the grave, and mentions a fact with regard to the ministerial labors of Dr. Alexander which may be new to some of our readers:

It is one of the most interesting and characteristic facts connected with his life, that while fulfilling the duties of Professor of Rhetoric and Belles Letter in the College of New Jersey, he preached regularly to a small congregation of colored people without compensation for some seven years. It was his delight and he felt it to be his honor to minister in the name of his Master to this humble people, and among the most affecting incidents connected with his burial was the gathering around his grave of a large number of those to whom he has so long broken the bread of life but a few steps from the spot where his body was laid.

The Christian Intelligencer adds:

The church of the late Dr. Alexander, corner of Fifth Avenue and Twenty-Ninth Street, was filled last Sabbath by a large audience. The pulpit, which was draped in black, was occupied by Rev. Dr. Van Zandt of the Reformed Dutch Church, who delivered an able and affecting discourse from Psalm 97—”Clouds and darkness are around about him; righteousness and judgment are the habitation of his throne.”

The discourse was listened to throughout with rapt attention. The services closed with singing—

“How blessed the righteous when he dies!

When sinks a weary soul to rest!”

[Anna Laetitia Barbauld, around 1773]

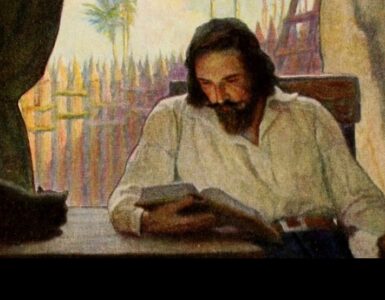

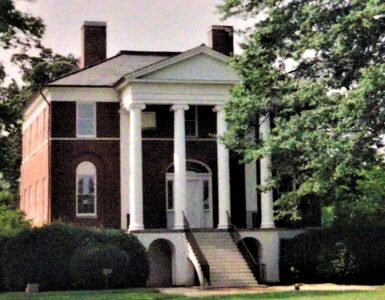

Notes—The header shows a building on the property where Alexander died, Sweet Chalybeate Springs (or Red Sweet Springs), Southern Guest Range, Alleghany County, Virginia, Historic American Buildings Survey, after 1933, Library of Congress Digital Collection; this photo was taken nearly a hundred years ago, my guess is there is not much left to this building barring any restoration that might have been done. Information about James Waddel is from William B. Sprague, Annals of the American Pulpit, vol. 3, pages 235-242; a memorial by Archibald Alexander for his grandfather is included on pages 240-242. The book, The Alexander Memorial, 1879, includes the memorial presented by T. L. Cuyler for J. W. Alexander on pages 19-27. The Duane Street Church is part of the ancestry of Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church and its genealogy is explained in the notes of the post on this site, “John B. Romeyn, Dutch-American Presbyterian.” A great source is The Life of J. W. Alexander: Forty Years of Familiar Letters, 2 vols., New York: Charles Scribner, 1860; the portrait of him in this post is from vol. 2 and appears to have been taken not long before his death. This post was first published Jan 30, 2014; it has been revised and much material added including the funeral article from The Central Presbyterian. Regarding the springs where Alexander died, see the article, “Red Sweet Springs (Sweet Chalybeate Springs)” on the University of Virginia website, https://exhibits.hsl.virginia.edu/springs/redsweet/index.html.