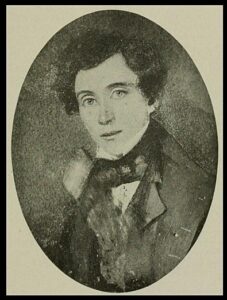

Thomas Smyth was born June 14, 1808 in Belfast, Ireland, the sixth son of Samuel and Ann Magee Smith. His father was a grocer and an elder in the local Presbyterian Church. Later in life Thomas would adopt the Smyth spelling to avoid confusion with another Old School Presbyterian minister named Thomas who spelled his surname Smith. He graduated Belfast College in 1829 after completing preparatory studies in the Academic Institute of Belfast which was associated with the college. He moved to America, enrolled in the senior class at Princeton Seminary, and completed theological studies in 1831. When he was ordained by Newark Presbytery the plan was for him to become a missionary to Florida. Florida had become a territory in 1821 and would become a state in 1845. William McWhir is sometimes considered the father of Florida Presbyterianism and Smyth would build upon his efforts. But before Smyth set out for the field, Second Presbyterian Church of Charleston corresponded with the Princeton faculty seeking a candidate to supply its pulpit. There was a Princeton-Charleston connection in that the organizing pastor of Second, Andrew Flinn, had been a board member of Princeton Seminary. Smyth was recommended for the position. He supplied Second beginning in 1831 and was soon offered a call to become pastor, however he was uncertain about remaining in Charleston in light of the opportunity for church extension in Florida. Smyth continued supplying Second while struggling with his opportunities until he gained peace about staying in Charleston and was installed pastor of Second Church in December in 1834.

Thomas Smyth was born June 14, 1808 in Belfast, Ireland, the sixth son of Samuel and Ann Magee Smith. His father was a grocer and an elder in the local Presbyterian Church. Later in life Thomas would adopt the Smyth spelling to avoid confusion with another Old School Presbyterian minister named Thomas who spelled his surname Smith. He graduated Belfast College in 1829 after completing preparatory studies in the Academic Institute of Belfast which was associated with the college. He moved to America, enrolled in the senior class at Princeton Seminary, and completed theological studies in 1831. When he was ordained by Newark Presbytery the plan was for him to become a missionary to Florida. Florida had become a territory in 1821 and would become a state in 1845. William McWhir is sometimes considered the father of Florida Presbyterianism and Smyth would build upon his efforts. But before Smyth set out for the field, Second Presbyterian Church of Charleston corresponded with the Princeton faculty seeking a candidate to supply its pulpit. There was a Princeton-Charleston connection in that the organizing pastor of Second, Andrew Flinn, had been a board member of Princeton Seminary. Smyth was recommended for the position. He supplied Second beginning in 1831 and was soon offered a call to become pastor, however he was uncertain about remaining in Charleston in light of the opportunity for church extension in Florida. Smyth continued supplying Second while struggling with his opportunities until he gained peace about staying in Charleston and was installed pastor of Second Church in December in 1834.

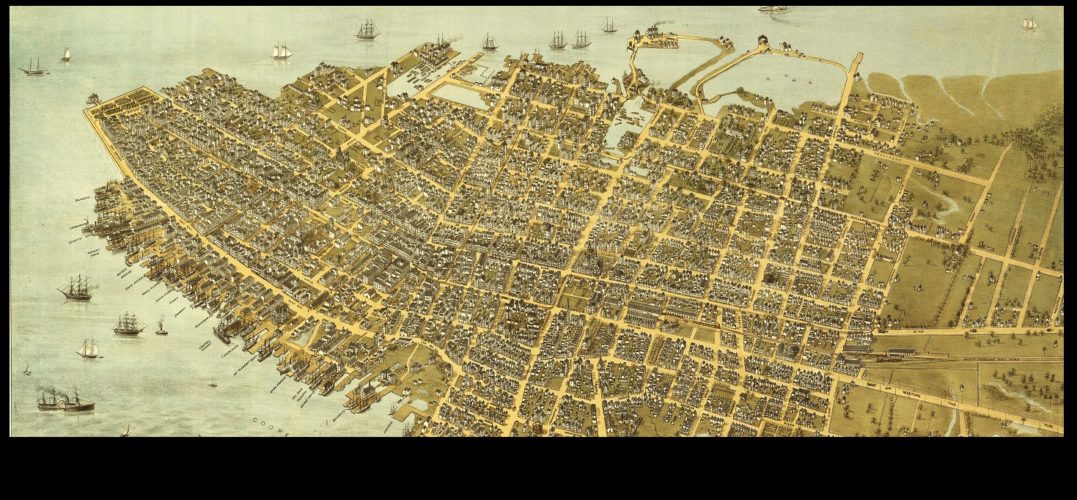

Shortly after Smyth’s arrival in Charleston he married Margaret Milligan Adger the daughter of James Adger who was a local businessman. The Adger family made a sizeable fortune via Charleston’s harbor and its busy docks. Currently there are two cobble-stoned roads off East Bay Street named “North Adgers Wharf” and “South Adgers Wharf.” These remnants of Charleston’s past provide reminders of the warehouses and shipping business operated by the Adger family. Margaret and Thomas were married July 9, 1832.

Shortly after Smyth’s arrival in Charleston he married Margaret Milligan Adger the daughter of James Adger who was a local businessman. The Adger family made a sizeable fortune via Charleston’s harbor and its busy docks. Currently there are two cobble-stoned roads off East Bay Street named “North Adgers Wharf” and “South Adgers Wharf.” These remnants of Charleston’s past provide reminders of the warehouses and shipping business operated by the Adger family. Margaret and Thomas were married July 9, 1832.

In 1838 Smyth published Manual for the Use of the Members of the Second Presbyterian Church, Charleston, S.C. Prepared Under the Direction of the Church, which is 234 pages long. It includes historical discourses, dedication sermons, lists of members and elders (also trustees, but no deacons), as well as a bibliography of recommended books, instruction in prayer, information about pastoral visits, and several other topical subjects to inform members and help them with their growth in grace. Also included are,

“Twelve Rules for Promoting Harmony Among Church Members.”

[see Notes]

- To remember that we are all subject to failings and infirmities of one kind or another. (Matthew 7:1-5; Romans 2:21-23).

- To bear with and not magnify each other’s infirmities. (Galatians 6:1).

- To pray one for another in our social meetings, and particularly in private. (James 5:16).

- To avoid going from house to house for the purpose of hearing news and interfering with other people’s business. (Leviticus 19:16).

- Always turn a deaf ear to any slanderous report and allow no charge to be brought against any person until well founded and proved. (Proverbs 25:23).

- If a member be in fault, tell him of it in private, before it is mentioned to others. (Matthew 18:15).

- To watch against shyness [suspicion] of each other, and put the best construction on any action that has the appearance of opposition or resentment. (Proverbs 10:12).

- To observe the just rule of Solomon, that is, to leave off contention before it be meddled with. (Proverbs 17:14).

- If a member has offended, consider how glorious, how God-like it is to forgive, and how unlike a Christian it is to revenge. (Ephesians 4:2).

- To remember that it is always a grand artifice of the Devil to promote distance and animosity among members of Churches, and we should, therefore, watch against every thing that furthers his end. (James 3:16).

- To consider how much more good we can do in the world at large and in the Church in particular when we are all united in love, than we could do when acting alone and indulging a contrary spirit. (John 13:35).

- Lastly, to consider the express injunction of Scripture and the beautiful example of Christ as to these important things. (Ephesians 4:32; 1 Peter 2:21; John 13:35). [pages 205-6]

If one verse were used to summarize these twelve rules it could be 1 Peter 4:8, Above all, keep loving one another earnestly, since love covers a multitude of sins.

Though Dr. Smyth was loved by his congregation, it does not mean they were happy with every aspect of his ministry. It was thought by some members that his sermons were too long. In order to remedy the situation a speaking tube was installed from the choir loft to the pulpit. The violinist was to speak to Smyth through the tube and tell him it was time to stop preaching. Despite the warnings echoing through the sound tube’s horn loud enough for people in the front pews to hear them, he paid no attention and continued to proclaim the Word at length. Another means of communicating the exasperation of some congregants with the length of sermons was a man throwing his hat in the aisle as a reminder to end the sermon, but that hint did not work either.

As with many ministers Smyth was afflicted with a severe case of bibliomania. He wrote to his wife during an extended trip,

My thirst for books in London became rapacious. I overspent my supplies in procuring them at the cheap repositories and left myself in the cold winter for two or three months without a cent.

Smyth was experiencing bibliomania in a way that had been expressed earlier by Erasmus of Rotterdam. When Erasmus was studying Greek he wrote to Battus,

I have been applying my whole mind to the study of Greek; and as soon as I receive any money I shall first buy Greek authors, and afterwards some clothes.

It is sad how bibliomania can bring one to live in tattered clothes for the sake of new books. Over the years, Smyth’s lust for books and just about anything else printed led to the accumulation of about 20,000 volumes as well as maps, documents, and ephemera. His compulsive book buying caused tension with his wife. In a letter in 1846, while they were constructing an addition to their house to make room for more books, she told him to control his spending,

I tell you this now as a preface to a caution, not to involve yourself too deeply or inextricably in debt by the purchase of books & pictures; of the last, with the maps, we have enough now to cover all the walls, even of the new rooms; & the books are already too numerous for comfort in the Study & Library. … But I would enter a protest not only against books & pictures, but all other things not necessary & which can come under the charge of extravagance. Do be admonished & study to be economical.

Margaret was exasperated with her husband for depleting the household funds in book buying binges. One can imagine the Smyth home with books packed everywhere, but as he aged, Smyth came to see that his days were numbered so he sold more than half of his library to Columbia Theological Seminary. He was concerned that since he could not take full advantage of his library and Margaret’s patience with his afliction was wearing thin, it would be best for students to have access to his unique and valuable books.

Thomas Smyth was a persistent student even as his physical problems increased. Health aside, he was still a prolific writer whose publications would be compiled in ten thick volumes after his death. His weakness was such in the later years that at one point the church constructed a saddle-like seat for him to use as he preached from the pulpit. Headaches were so severe that he would stick his head in a bucket of ice water for relief. Smyth continued to shepherd his sheep as he could, but he succumbed to the frailty of fallen flesh and passed away in Charleston, August 20, 1873. He had served his church for over forty years. He, Margaret, and several family members are buried in the churchyard of his first and only pastoral charge. Six of the Smyths’ nine children survived to become adults. One son was Ellison Adger Smyth who owned textile mills in South Carolina and was a benefactor of Presbyterianism in the state. Thomas Smyth was honored by the College of New Jersey (Princeton) with the Doctor of Divinity in 1843.

A PDF index to the ten volumes of Smyth’s works has been compiled by the author of this site and is available for free on the PCA Historical Center website at this link. The volumes themselves as well as other works are available in PDF on the Log College Press website at “Thomas Smyth, 1808-1873.”

Barry Waugh

Notes–(The following was added July 17, 2025) Thank you to Andrew Myers of Log College Press for pointing out the note in Smyth’s Manual at the end of “The Twelve Rules” that was missed by the author. The note credits William S. Plumer for the likewise titled list in his Manual for the Members of the Presbyterian Church in Petersburg, Virginia, Prepared by the Present Pastor, Petersburg: Yancey & Wilson, July 1833. Smyth’s “Rules” were reprinted in vol. 5 of the Complete Works of Thomas Smyth, D.D., 1908, page 189, where a note once again credits Plumer.

The header is from the Library of Congress Online Digital Collection and is titled “Birds Eye View Charleston, South Carolina,” and it shows the city just a year before Smyth died. The primary source used was Autobiographical Notes, Letters and Reflections, by Thomas Smyth, as edited by his granddaughter, Louisa Cheves Stoney, 1914; the portraits are from this book. Erasmus’s quote was found in the translation of his letter to Battus of April 12, [1500], in The Epistles of Erasmus from His Earliest Letters to his Fifty-First Year Arranged in Order of Time, vol. 1, New York, 1901, as translated by F. M. Nichols, page 236.