In 1728 Alexander and Jane Preston arrived in the port of Philadelphia, then a decade later settled in the Shenandoah Valley in the region that became Staunton, Virginia. Farming was hard work but it was the way of life for many Presbyterian settlers on the frontier if they hoped to be free from the Church of England. These religious nonconformists wanted to practice means of grace worship and raise their children in the way they should go by using Scripture as interpreted by the Westminster Standards. The Prestons would raise seven children to join their household labor pool to till the soil while each child was being trained in general and catechetical studies. In 1741 Alexander was selected a member of the committee for building a meetinghouse for the Tinkling Spring Presbyterian Church. When he died in 1744 he was buried in the church yard in an unmarked grave, possibly due to finances or maybe there was no one skilled enough to cut and engrave the stone. However, the omission was rectified in later years when descendants purchased an obelisk monument for his grave that was funded in part by Alexander’s great grandson, Robert Jefferson Breckinridge.

In 1728 Alexander and Jane Preston arrived in the port of Philadelphia, then a decade later settled in the Shenandoah Valley in the region that became Staunton, Virginia. Farming was hard work but it was the way of life for many Presbyterian settlers on the frontier if they hoped to be free from the Church of England. These religious nonconformists wanted to practice means of grace worship and raise their children in the way they should go by using Scripture as interpreted by the Westminster Standards. The Prestons would raise seven children to join their household labor pool to till the soil while each child was being trained in general and catechetical studies. In 1741 Alexander was selected a member of the committee for building a meetinghouse for the Tinkling Spring Presbyterian Church. When he died in 1744 he was buried in the church yard in an unmarked grave, possibly due to finances or maybe there was no one skilled enough to cut and engrave the stone. However, the omission was rectified in later years when descendants purchased an obelisk monument for his grave that was funded in part by Alexander’s great grandson, Robert Jefferson Breckinridge.

Who was Robert Jefferson Breckinridge?

Robert Jefferson was the third son born to John and Mary Breckinridge at Cabell’s Dale, Kentucky, March 8, 1800. His father was a farmer whose financial success made for a schedule allowing time for public service including his term as the United States Attorney General during the administration of President Thomas Jefferson. John was a true republican and thus the Breckinridges’ infant son was given the middle name Jefferson. Robert was just six years old when his father died. As he matured, studies included curriculum directed by Dr. Louis Marshall, the brother of Chief Justice John Marshall. Eldest Breckinridge son was Cabell who had graduated from Princeton in 1810, and at the time Robert was considering a college to attend his brother John was attending Princeton. Unsurprisingly, Princeton was chosen and Robert enrolled in the sophomore class in February of 1817. He did well until he lost his temper and engaged in a fight that led to his suspension. He was restored to his class when the suspension ended, but the experience did not leave him with a good opinion of Princeton, so he withdrew with an honorable dismissal. Robert then went to Yale to finish college, but after three months he found out that a year residency was required to graduate. He was unwilling to meet this requirement, so he transferred to Union College where he graduated in 1819 with the Bachelor of Arts. President Eliphalet Nott was just fifteen years into his sixty-two year tenure as president of Union at the time. The suspension from classes, in the end, did not keep Robert from being given an honorary Master of Arts by Princeton in 1832.

With his grand old college days behind and degree in hand, Robert returned to the beauty of Kentucky bluegrass and the familiarity of the family estate. The trouble was he had no sense of vocational direction. The Breckinridges were a wealthy family leaving Robert to live the high life as a man-about-town wandering from party to party, dance to dance, and bar to bar. Horse racing was a popular event for gentlemen of the era and Robert found a day at the races to be most delightful. He also was a frequent participant in games of chance in Frankfort, the state capital, and in Lexington. During one of his partying trips to Frankfort, he offended a man who challenged him to a duel. Breckinridge refused to accept the challenge resulting in his being called a coward. He purchased a pair of pistols to prepare for a duel, but it never took place. Through the intervention of the Masonic lodge, of which both men were members, a reconciliation was achieved and the matter ended. Robert’s boisterous lifestyle that had caused disciplinary action at Princeton followed him into his wandering post-graduate years.

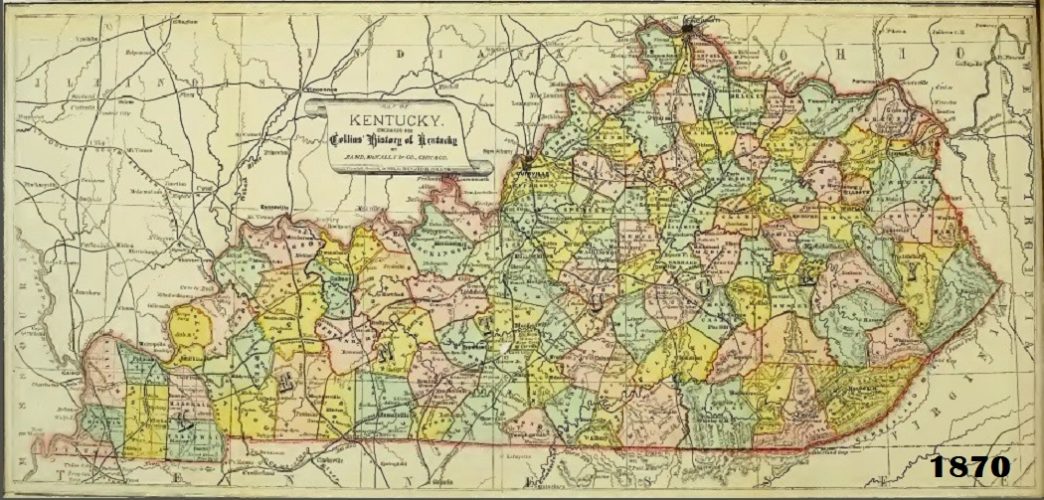

Within the course of a few years there would be some major changes in Robert’s life. During the summer of 1822, he became romantically interested in his second cousin Ann Sophonisba Preston of Virginia. On March 11, 1823, the two were married in her home in Abingdon. Robert’s older brother Cabell encouraged him to practice law and directed his reading, but when he died suddenly in September 1823 management of the Breckinridge estate fell to Robert. Combined with family responsibilities he would practice law beginning with completion of the bar exam January 3, 1824. The practice of law did not satisfy Robert; he had a desire to follow in the Breckinridge tradition of public service. In November 1825 he was elected to a first term in the House of the Kentucky Legislature and was then reelected three more times serving until late 1828 when he removed himself from public office.

Robert left public service because of personal difficulties he was facing. Following an illness that nearly caused his death, his daughter Louisiana died in 1829. Before Louisiana’s death another daughter had died. Through these troubling events and under the influence of his brother John Breckinridge, who was a Presbyterian minister in Baltimore, he was converted by God’s grace. He made his profession of faith in Christ in the McChord Presbyterian Church of Lexington, as did Ann, but they soon transferred to the Mt. Horeb Church near Lexington in Fayette County.

Robert’s conversion affected his thinking about the issues of the day. He decided in the summer of 1830 to appear one more time before the people of Kentucky as a political speaker. He spoke against enslaving Africans and the transportation of mail on the Sabbath. He saw it as his Christian responsibility to speak against these reoccurring issues which he believed were gross evils in the nation. Robert also participated in and hosted what were called woods-meetings, which were parachurch evangelism and revival gatherings. It was through the influence of such a meeting during the fall of 1831 that he felt called to the ministry. Pursuing the proper course for presbytery oversight he came under the care of the West Lexington Presbytery. During his examinations it was commented by one senior presbyter that:

Brethren, you had better be careful how you receive young Mr. Breckinridge, he will either make or break the Presbyterian Church. Before his conversion, he was considered the best dancer, the best hunter, and best stump speaker in Kentucky. (Sanders, Sketch, p. 18)

In the day social dancing was considered a worldly activity to be avoided by Christians. Seven months later on April 5, 1832 he was licensed to preach. Following the General Assembly of 1832, where he sat as a Ruling Elder commissioner, he moved to Princeton to study theology for a few months under the direction of seminary professor Samuel Miller. Miller was brother John’s father in law. Robert left Princeton when he received a call to pastor Second Presbyterian Church of Baltimore succeeding John. He was ordained and installed in November of 1832 and he served the church for twelve years.

While in Baltimore, Robert was confronted with the differences between the Old School and New School. In 1833, the moderator of the General Assembly was Dr. William A. McDowell, the pastor of Third Presbyterian Church, Charleston, South Carolina. While McDowell was enroute from Charleston to accept the post of General Agent for the Board of Missions in Philadelphia, he stopped in Baltimore to lead revival services for Robert Breckinridge. Over one hundred thirty were said to be converted with ninety of that number seeking admission to Third Church. Robert was excited by the results of the services but his jubilation was tempered by counsel from John, Samuel Miller, and his friend, Joshua Wilson. These men warned him of the dangers of using measures such as the anxious bench in the highly emotional climate of a revival. His counselors were even more concerned that Robert had abandoned the doctrine of limited atonement. One correspondent, Ezra Styles Ely, encouraged Robert to continue using revival measures despite criticism by the Old School, however influence from his Old School counselors led to his fervent affirmation of Calvinist orthodoxy.

During Robert’s pastoral years in Baltimore the increasing differences between the Old and New School perspectives led to a division of the Presbyterians. According to Edgar Mayse, R. J. Breckinridge was viewed by the New School as the foremost and most intolerable proponent of Old School views (109ff). There were several issues between the Old and New Schools. One issue exemplifying the differences is seen in Breckinridge’s contention that the office of ruling elder had fallen into disuse due to the New School’s depreciation of its importance. This failure to use the office of ruling elder properly was specifically challenged by Breckinridge with respect to the Synod of the Western Reserve. He contended that the roots of the elder problem were seen in a disparagement of the Westminster Confession of Faith by the Synod of the Western Reserve resulting in men being ordained without subscribing to the Presbyterian standards. Another issue for both Robert and John involved how missions were to be conducted and governed; the brothers believed that missions were to be directed by the courts of the Presbyterian Church through its boards and not through voluntary agencies (i.e. what we today might describe as non-denominational or para-church mission organizations). The voluntary agencies were viewed by the Old School as a threat to the proper oversight of missionary work because they were not under full control of the Presbyterian Church. For Robert Breckinridge, the ministries of the church should be under the direct rule and discipline of the church. The proper application of church polity to missionary ministry; the significance of the office of ruling elder; and the ever present antebellum issue of slavery were some of the key topics leading to the division of Presbyterians in 1837, but at its foundation the problems the Old School saw in the New School grew out of the issue of subscription.

The two sides in the Presbyterian conflict continued to polarize as further points of disagreement came to the fore. The signing of the Act and Testimony of June 1834, which was spearheaded by R. J. Breckinridge, defined the main points of contention between the Old School and the New School and angered the New School because it was composed and adopted by what they believed was effectively a para-church meeting of Old School adherents. Robert Breckinridge was chiefly responsible for composition of the Act and Testimony and he was seen as one of the more stringent Old School men. Charles Hodge, Samuel Miller and others believed a more moderate course than using the Act and Testimony would have been the better route. Differences increased with the Albert Barnes case as the Old School men contended that his teachings on important elements of biblical doctrine were in error, but the New School wanted to allow Barnes the freedom to differ. The result of the disagreement was the ejection of the New School in 1837 leaving the Old School to continue as the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America.

The Old School continued its ministry in both the north and south of the nation, and Robert Breckinridge was an active participant in the Old School’s work. He continued to minister as a pastor in Baltimore following the upheaval of 1837. He was honored by the Old School in 1841 when he was elected moderator of the General Assembly.

The next few years of Breckinridge’s life would be painfully eventful. A particularly difficult aspect of the Baltimore years was the death of his wife Ann in 1844. Maybe it was the lingering memories of life in Baltimore with Ann that contributed to him accepting the presidency of Jefferson College in Pennsylvania in 1845. His brother John had advised him not to take the position. Maybe John was right because college administration did not turn out to be Robert’s cup-of-tea and after two trying years he left the presidency to accept a call to pastor the First Presbyterian Church of Lexington, Kentucky. The years following his return to Kentucky were good because he was awarded the LL.D. by Washington and Jefferson College, he married the widowed Virginia Hart Shelby, and he was appointed superintendent of public instruction for the state of Kentucky. It was the latter in which Breckinridge excelled because during his six years of service he saw school attendance grow from 20,000 to over 200,000. Robert Breckinridge is still considered an important figure in the development and growth of the Kentucky public school system.

Robert’s next move would be his last and it may have been the most suitable ministry for a man of his experience and temperament. He left public service work to become the first Professor of Exegetic, Didactic and Polemic Theology in the new Presbyterian seminary at Danville, Kentucky. The seminary at Danville had been established by the General Assembly in May 1853 and its first session began October 13 that year. The original appointees for faculty included E. P. Humphrey, B. M. Palmer, Phineas P. Gurley, and Breckinridge, but Palmer and Gurley declined. The two who declined were replaced with Stuart Robinson and Joseph G. Reaser. As the sectional crisis increased and Robert’s ministry at Danville developed, he faced another difficult time. Once again, in 1859, he lost his wife. Virginia and Robert had three children, one of which, Nathaniel Hart, had died when he was only three years old. Breckinridge served out his active years as a professor until retirement in 1869.

While Robert served at Danville, he had an opportunity to preach at the Second Presbyterian Church, Charleston, South Carolina, during the ministry of Thomas Smyth. One woman observing the sermon said in a letter dated June 6, 1860 that:

Dr. R. J. Breckinridge preached here last Sabbath Day; I suppose his reputation is too well known for me to say anything to you about him, yet his feeble voice, want of teeth, and want of all the graces of an Orator, caused a severe disappointment among the vast audience who had collected to hear him. (Smyth, Autobiographical Notes, 557-58)

On the eve of secession, maybe this Southern lady’s perspective was prejudiced by Breckinridge’s residency in the border state of Kentucky which allowed slavery but sided with the free North.

The Civil War has been described as the war of brother against brother and father against son, which was especially the case for the Breckinridges. As the conflict progressed and victory seemed likely for the Union, Kentucky turned more of its support to the Confederacy because of Lincoln’s emancipation of the slaves. This conflict within Kentucky was reflected among Robert’s descendants and kin. His sons Robert Jr. and Willie took sides with the South against their father. Issa Breckinridge, Willie’s wife, was particularly angry with her father in law and his support of the Union, so in protest she would not allow him to visit two of their newest children. Fortunately, Willie convinced her otherwise in 1867. Theophilus Steele, the husband of Robert’s daughter named Sophonisba, put on Confederate gray and rode with John Hunt Morgan. It is likely that when Morgan’s men were captured Robert’s influence with the Union resulted in Theophilus being kept a prisoner of war rather than suffering execution as a guerilla raider. Robert’s nephew, John C. Breckinridge, became a Southern Democrat candidate for the presidency when the pro-slavery forces were the minority at the 1860 Democratic National Convention that nominated Stephen A. Douglas to run against Lincoln. Despite these kin turning against R. J., his sons Joseph and Charles along with three sons-in-law fought with Lincoln’s forces.

The tensions Robert faced within Kentucky increased when he was nominated to the Baltimore convention that re-nominated Lincoln in 1864. He made a speech at the convention denouncing the anti-Union position of many Kentuckians. James Klotter notes that James G. Blaine, who had just entered the U. S. House of Representatives in 1863, commented that Breckinridge’s appearance was strong and “patriarchal” and that his speech was the most inspiring of the convention (85-86). The speech was against slavery and Blaine’s praise reflects his sectional perspective just as the lady from Charleston showed her southern sympathies in her assessment of Breckinridge. Lincoln managed to carry Kentucky in 1864 with the smallest margin of victory achieved by any of the states voting in favor of his return to office.

The closing years of Breckinridge’s life included another marriage after eight years as a widower. His third wife was Margaret Faulkner White whom he married November 5, 1868. As age slowed Robert Jefferson Breckinridge he left his professorship at Danville in December 1869. He died in Danville December 27, 1871 after several months of illness.

Breckinridge’s life and work had been tumultuous and colorful. He had survived as a vocal opponent of slavery in Kentucky; he had been a leader of the Old School in its ejection of the New School; he had improved the quality and quantity of Kentucky education; and he had worked to bring ministerial education to the rough Kentucky frontier at Danville Seminary. Just as he came from a notable ancestry, his family and descendants also enjoyed prominence. Robert and his first wife Ann had eleven children together, six girls and five boys. One daughter, Mary Cabell, married William Warfield in 1848 and on November 5, 1851, Benjamin Breckinridge was born. B. B. Warfield would mature in Kentucky, graduate Princeton University, and then enter the ministry following studies at Princeton Seminary. Warfield went on to serve as Professor of New Testament at Western Theological Seminary then move on to Princeton to become Professor of Theology at the seminary. Robert’s son William “Willie” Campbell Preston Breckinridge married a Kentuckian named Lucretia Clay who was the granddaughter of Henry Clay. Like his grandfather in law, Willie worked in politicsby serving in the United States House of Representatives 1885 to 1896. Robert’s second wife, Virginia Hart Shelby, had been married to Alfred Shelby who was the son of Isaac Shelby, Kentucky’s first governor. Isaac also fought in the Revolutionary War and commanded the troops that defeated the British at the battle at King’s Mountain, North Carolina.

Barry Waugh

More information about Breckinridge is available on this site in the posts, “Robert J. Breckinridge, Remembered by James F. Clarke,” and “A Belligerent D.D. Robert J. Breckinridge.” He is also mentioned in the post, “Samuel M. Breckinridge, A Christian Gentleman.”

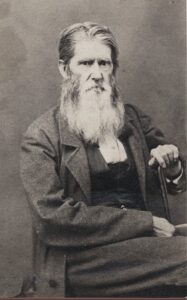

Notes—A collection of Breckinridge’s works in PDF is available for free on the Log College Press site, at “Robert Jefferson Breckinridge (1800-1871).” The portrait of Dr. Breckinridge was provided by Director Wayne Sparkman of the PCA Historical Center; the photographer has captured the man based on descriptions given in sources—a distinguished and opinionated man at three-score-and-ten. Howard McKnight Wilson, The Tinkling Spring: Headwater of Freedom, A Study of the Church and Her People, Fisherville: The Tinkling Spring and Hermitage Presbyterian Churches, 1954. Autobiographical Notes, Letters and Reflections, by Thomas Smyth, was edited by his granddaughter, Louisa Cheves Stoney, 1914. Richard D. Brown, The Presbyterians: Two Hundred Years in Danville, 1784-1984, Danville: Presbyterian Church, 1983. General Catalogue of Princeton University, 1746-1906, Princeton: Published by Princeton University, 1908. James C. Klotter, The Breckinridges of Kentucky 1760-1981, Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1986. Edgar C. Mayse, Robert Jefferson Breckinridge: American Presbyterian Controversialist, Ph.D. Dissertation, Richmond: Union Theological Seminary, 1974; this is a massive and informative work in two volumes. Alfred Nevin, Encyclopedia of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, Philadelphia: Presbyterian Publishing Company, 1884. Robert S. Sanders, Sketch of Mount Horeb Presbyterian Church, 1827-1952, [n.p,][n.d.]. Gardiner H. Shattuck, Jr., “Breckinridge, Robert Jefferson.” American National Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Ellis M. Coulter, “Breckinridge, Robert Jefferson.” Dictionary of American Biography, ed. Allen Johnson, American Council of Learned Societies, Centenary Edition, New York: Scribner’s, 1929, 1946. Ernest Trice Thompson, Presbyterians in the South, Vol. 1, 1607-1861, Richmond, VA: John Knox Press, 1963.