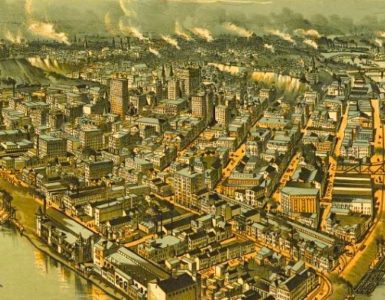

Catastrophes redirect people from the temporal to the eternal. After 911, many confused, disconsolate, and mourning individuals who formerly had little thought of God went to churches seeking answers to their questions. God uses floods, fires, whirlwinds, earthquakes, and other major events to bring his people to faith in Christ. The fire in Richmond’s theater on December 26, 1811, killed over eighty people including Virginia’s governor and it injured many others. It was a horrifying blaze as the flames spread rapidly across dry wood and fabric, but the horror became tragic because people could not escape through the theater’s inadequate passages, a constricted stairway, and too few exit doors. Meredith Henne Baker’s The Richmond Theater Fire recounts the event in all its details; shows how Richmonders chose to memorialize the dead; and then tells how memory of the fire influenced the city and nation in subsequent years. Baker emphasizes how the nearly church-less city of Richmond harvested from its non-religious residents many that became Christians and seeded new congregations or were added to the few existing ones.

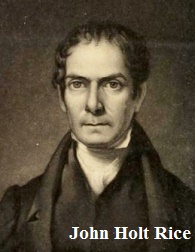

Baker recounts the post-fire ministries of Episcopalians, Baptists, and Methodists, and a good bit of the text is dedicated to three Presbyterian ministers that would become particularly important for American theological education. Archibald Alexander was at the time the minister of Pine Street Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia and would in 1812 become the first professor of the Presbyterian seminary at Princeton. Samuel Miller was serving in a collegiate pastorate in New York with John Rodgers. Miller would be appointed Alexander’s colleague at Princeton in 1813. John Holt Rice, at the time pastoring rural congregations in Virginia, would soon become the minister of Richmond’s First Presbyterian Church and then in later years direct Union Seminary in Virginia through some difficult times to bring stability and prepare it for the future.

There were many sermons delivered across the nation following the fire other than those of Alexander, Miller, and Rice, some of them would relate the catastrophe to what were known as worldly amusements. Such amusements included social dancing, card playing, games of chance, and attending the theater, among others. Note that the theater in the era was not always considered a proper place for Christians because theaters could vary in propriety from base dives and gratuitous indecency to more acceptable forms such as the performance presented by Placide and Green Company of Charleston, South Carolina, in the Richmond theater the night of the fire. In the paragraphs that follow, I will look into the perspectives on the fire presented by three Presbyterian ministers considered in Baker’s book.

Alexander’s sermon was delivered in Pine Street Church in Philadelphia, and then published in a pamphlet titled, A Discourse Occasioned by the Burning of the Theatre in the City of Richmond, Virginia. His text was the second half of Romans 12:15, “Weep with them that weep.” After several pages of compassionate comments and encouragement directed to those in mourning, he transitioned into the subject of worldly amusements. Alexander expressed reluctance to broach the topic but since some had asked him to do so, he made a few comments that fill less than two pages. He did not target the theater in particular but worldly amusements in general commenting that they were “unfriendly to piety.” Then, he began an extended section pointing out the brevity of life, the importance of Christian commitment, the need to avoid temptation, and the requirement of heavenly minded thinking. The overall tone of the discourse is pastoral and Alexander is reserved in his comments about entertainment. His primary concern was to bring comfort to his listeners as they lived through the fire’s aftermath, challenge Christians to commit to better service for the Lord, and call the unbelieving to faith.

Alexander’s sermon was delivered in Pine Street Church in Philadelphia, and then published in a pamphlet titled, A Discourse Occasioned by the Burning of the Theatre in the City of Richmond, Virginia. His text was the second half of Romans 12:15, “Weep with them that weep.” After several pages of compassionate comments and encouragement directed to those in mourning, he transitioned into the subject of worldly amusements. Alexander expressed reluctance to broach the topic but since some had asked him to do so, he made a few comments that fill less than two pages. He did not target the theater in particular but worldly amusements in general commenting that they were “unfriendly to piety.” Then, he began an extended section pointing out the brevity of life, the importance of Christian commitment, the need to avoid temptation, and the requirement of heavenly minded thinking. The overall tone of the discourse is pastoral and Alexander is reserved in his comments about entertainment. His primary concern was to bring comfort to his listeners as they lived through the fire’s aftermath, challenge Christians to commit to better service for the Lord, and call the unbelieving to faith.

Samuel Miller delivered his sermon to a group of “young gentlemen” at their request. He was specifically asked to include in his discourse comments about theatrical entertainments. He was, like Alexander, reluctant to do so, but again like Alexander, he addressed the issue. The two verses he selected for exposition were Lamentations 2:1, 13.

Samuel Miller delivered his sermon to a group of “young gentlemen” at their request. He was specifically asked to include in his discourse comments about theatrical entertainments. He was, like Alexander, reluctant to do so, but again like Alexander, he addressed the issue. The two verses he selected for exposition were Lamentations 2:1, 13.

How hath the Lord covered the daughter of Zion with a cloud in his anger, and cast down from heaven unto the earth, the beauty of Israel, and remembered not his footstool in the day of his anger! … What thing shall I take to witness for thee? What thing shall I liken to thee, O daughter of Jerusalem? What shall I equal to thee, that I may comfort thee, O virgin daughter of Zion? For thy breach is great like the sea; who can heal thee?

Lamentations mourns the destruction of Jerusalem and shows God’s sovereign right to have brought judgment on Judah. Miller turns his hearers first to consider God’s providence in the Richmond fire and then focused their attention on the healing that only the Lord could provide. Expressions of sympathy and examples of individuals from history that suffered are presented by Miller to provide solace for his listeners. Several Bible texts are alluded to and quoted. After about four pages of empathy and encouragement, the moral application of the calamity to Richmond and the nation is addressed. Miller says:

I am persuaded that the Calamity which we lament, ought to be employed, among other purposes as an occasion of entering a solemn protest against a prevailing, but most unchristian and most baneful Amusement.

He then begins to give his “impressions of the THEATRE.” From this point on for several pages, Miller condemns the theater as a terrible influence on society and responds to likely objections made against his arguments opposing the theater. The case is thoroughly presented. Dr. Miller had numerous comments—theater is a waste of time; it is operated by people of questionable character; it provides manifold opportunities for temptation as sin is presented in a positive light; and good stewardship dictates that the admission fee could be spent on more productive and pious endeavors. Several other issues are pointed out such as defenders of the theater observing that not all plays are the same because some have intellectual and contemplative value, to which Miller responded that the factors mitigating against the little benefit gained means the time used in attendance could be better spent elsewhere. Miller makes a strong case against the theater which readily could be expanded to include other worldly amusements. The trouble is, his arguments could be used against participating in and viewing sports, joining men’s social clubs that were so popular in the day, and even something required for life, eating, which if done in the taverns of Miller’s day might occur in a boisterous environment as inebriated customers lost their inhibitions. Scripture tells Christians that they are to be in the world but not of the world and church history has shown that a reoccurring problem is knowing at what point the believer crosses the line and becomes not only in the world but of it as well. Dr. Miller made some good points in his case that are worthy of contemplation, but as he addressed objections to his views, his responses increasingly become strained. The presentation of his message at some points during his theater comments is—as much as one can tell from reading the text and not seeing him live in the pulpit—one of reprimand and rebuke (if seen live, his mannerisms and tone of voice might have softened the words). Where Alexander emphasized comfort for Richmond and the nation as expressed in his Bible text regarding weeping, Miller’s passage rebuked the people in a difficult time.

Unfortunately, a copy of John Holt Rice’s sermon from Romans 15:29—“And I am sure that, when I come unto you, I shall come in the fullness of the blessing of the gospel of Christ,” was not available to me. When Rice delivered his message he did so extemporaneously because until someone in the congregation informed him of the fire on Sunday morning, he had not heard about it. He set aside his prepared message. According to Baker, it was an evangelistic sermon that influenced at least one woman in the congregation with the gospel (pp. 197-98). However, nothing can be said about whether Rice addressed worldly amusements or not. Rice and Alexander’s verse selections were both taken from Romans with Rice’s emphasizing the gospel and Alexander’s calling his listeners to weep and show empathy with the disconsolate, while Samuel Miller’s selection from Lamentations showed that the destruction of Jerusalem was the just and righteous act of God and applied it to the theater fire.

Unfortunately, a copy of John Holt Rice’s sermon from Romans 15:29—“And I am sure that, when I come unto you, I shall come in the fullness of the blessing of the gospel of Christ,” was not available to me. When Rice delivered his message he did so extemporaneously because until someone in the congregation informed him of the fire on Sunday morning, he had not heard about it. He set aside his prepared message. According to Baker, it was an evangelistic sermon that influenced at least one woman in the congregation with the gospel (pp. 197-98). However, nothing can be said about whether Rice addressed worldly amusements or not. Rice and Alexander’s verse selections were both taken from Romans with Rice’s emphasizing the gospel and Alexander’s calling his listeners to weep and show empathy with the disconsolate, while Samuel Miller’s selection from Lamentations showed that the destruction of Jerusalem was the just and righteous act of God and applied it to the theater fire.

In conclusion, the comments made against the theater could lead readers to think that the Richmond fire was a judgment against the people in attendance because they patronized the theater. This is considerably less the case for Alexander than Miller, Rice’s view cannot be determined. The reluctance of the future Princetonians to address the evils of the theater could reflect their understanding that even with careful composition their words might be understood to say that the fire was God’s judgment. God may and does bring judgments in this world, but it is wrong to conclude that an event like the Richmond theater fire was God using the catastrophe to judge the audience. For example, if it had pleased God to judge with death the governor of Virginia, would it not have made more sense to simply remove from him alone the breath of life? Were the Richmonders in the theater more sinful than the men down the street visiting prostitutes in the seedy upstairs rooms of the tavern? If for some reason the Lord was brining judgment on the people in the theater, it was within the secret counsel of his will. Jesus addressed this issue in Matthew 13:1-5 when He simply and forthrightly said the tragedies mentioned in the verses were to bring people to repentance. Thus, 911 and the Richmond theater fire were tragic, upsetting, and frightening events, but their purpose is to bring fallen sinners to the One who is the only redeemer of God’s elect, the Lord Jesus Christ. World events and disasters in creation prick the sense of deity in man and they can be used to challenge the unbelieving with the gospel message of Christ.

Barry Waugh

Notes—the header image is of Monumental Church in Richmond which was built to remember the victims of the theater fire; the image is from the New York Public Library public domain digital collection. There were two plays on the program that night: “The Father; or, Family Feuds,” and “Raymond and Agnes: or, the Bleeding Nun.” The copy of Samuel Miller’s sermon used for this post is nicely presented and was found on, covenanters.org, which is operated by the Reformed Presbyterian Church (Covenanted)—”Steelite” Covenanters. For more writings by Samuel Miller see the collection on Log College Press, and Alexander’s sermon is available at Log College Press in its Archibald Alexander collection. The bibliographic information for the book mentioned is, Meredith Henne Baker, The Richmond Theater Fire: Early America’s First Great Disaster, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2012.