Seminary education in the nineteenth century was challenging especially as developed and standardized by the first seminary of the Presbyterian Church established in Princeton, New Jersey, 1812. The curriculum included the biblical languages of Greek and Hebrew, English Bible, textual analysis of the Bible and its interpretation, Bible history, didactic theology, church government, pastoral care, homiletics (preaching), and church history. Added to the Greek and Hebrew languages was prerequisite Latin which was especially important at Princeton. The theology curriculum used the Latin works of Francis Turretin and Charles Hodge’s Systematic Theology included lengthy Latin quotations. Added to English, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, a motivated student might include German to defend the doctrine of Scripture against German higher-critical academics. It was quite a program of study and may make current seminary students feel deprived or possibly intimidated. When young Fentress entered Princeton Seminary he did so with another challenge because all the reading and writing required of him would be hampered by visual blindness.

Seminary education in the nineteenth century was challenging especially as developed and standardized by the first seminary of the Presbyterian Church established in Princeton, New Jersey, 1812. The curriculum included the biblical languages of Greek and Hebrew, English Bible, textual analysis of the Bible and its interpretation, Bible history, didactic theology, church government, pastoral care, homiletics (preaching), and church history. Added to the Greek and Hebrew languages was prerequisite Latin which was especially important at Princeton. The theology curriculum used the Latin works of Francis Turretin and Charles Hodge’s Systematic Theology included lengthy Latin quotations. Added to English, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, a motivated student might include German to defend the doctrine of Scripture against German higher-critical academics. It was quite a program of study and may make current seminary students feel deprived or possibly intimidated. When young Fentress entered Princeton Seminary he did so with another challenge because all the reading and writing required of him would be hampered by visual blindness.

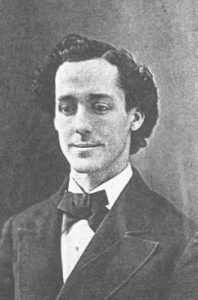

William Henry was born the son of Bennett and Agnes Fentress in Baltimore, Maryland, March 25, 1851. Agnes was from Scotland having emigrated in 1818 with her parents George and Margaret Clasey. Agnes’s parents were founding members of Light-Street Presbyterian Church in Baltimore. As a child, William’s mother prayed that he would become a minister, but her hope for his future was dimmed when at the age of six he lost his sight. However, despite his considerable handicap, William pursued formal education beginning at the age of nine in the Maryland Institute for Instruction of the Blind where he continued as a state beneficiary beginning May 7, 1860 until he completed the program June 1, 1868. He then began college studies through tutoring provided by Professor Wagner of Baltimore before continuing formally at Richmond College in Virginia graduating in 1870.

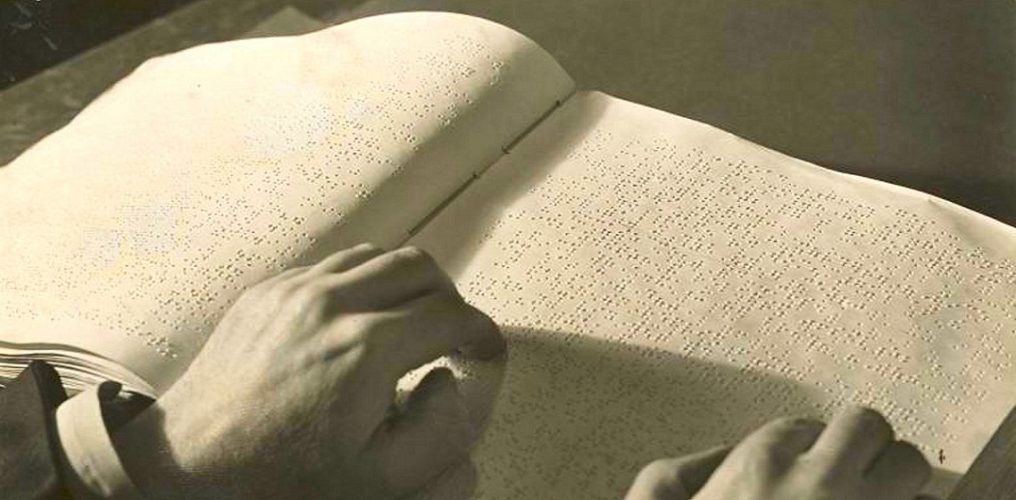

William returned to Baltimore to reside at 219 Montgomery Street which was about a twenty minute walk from his church, Central Presbyterian located at the corner of Saratoga and Liberty streets. The church had been organized under the ministry of Stuart Robinson in 1853 but at the time of William’s membership the pastor was Joseph T. Smith. He professed faith in Christ at the age of twenty one. His mother’s prayers combined with his own sense of calling caused him to continue studying in preparation for the ministry. In a letter to Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe of the Perkins School for the Blind in Boston, where Helen Keller would study, he asked where “Latin Books in raised print” including dictionaries and grammars could be purchased and “the respective prices of the same.” Raised print refers to an early form of text for the blind that used the full form of each letter pressed into the sheet sufficiently for it to project from the outside surface in relief so it could be read by touch. For those who remember the antique device known as a typewriter, the letters on the paper would have looked like the letters projecting from the individual character hammers actuated by typewriter keys. Dr. Gridley’s suggestions must have proved beneficial because William was accepted for study at Princeton Seminary.

William returned to Baltimore to reside at 219 Montgomery Street which was about a twenty minute walk from his church, Central Presbyterian located at the corner of Saratoga and Liberty streets. The church had been organized under the ministry of Stuart Robinson in 1853 but at the time of William’s membership the pastor was Joseph T. Smith. He professed faith in Christ at the age of twenty one. His mother’s prayers combined with his own sense of calling caused him to continue studying in preparation for the ministry. In a letter to Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe of the Perkins School for the Blind in Boston, where Helen Keller would study, he asked where “Latin Books in raised print” including dictionaries and grammars could be purchased and “the respective prices of the same.” Raised print refers to an early form of text for the blind that used the full form of each letter pressed into the sheet sufficiently for it to project from the outside surface in relief so it could be read by touch. For those who remember the antique device known as a typewriter, the letters on the paper would have looked like the letters projecting from the individual character hammers actuated by typewriter keys. Dr. Gridley’s suggestions must have proved beneficial because William was accepted for study at Princeton Seminary.

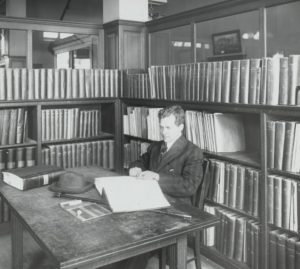

He travelled to Princeton to enter the seminary’s three-year divinity program in 1873. He learned his lessons almost wholly through the use of readers. In an alumni information form completed shortly before his death, William told how he learned his lessons.

I pursued … collegiate and theological studies almost altogether by means of readers. My classmates at Princeton Seminary were very thoughtful and kind in the number of their many attentions to me. I have also a very grateful remembrance of all the professors.

Student colleagues may have organized a rotation so that through their many eyes each reader would have a lighter load with all helping their brother in Christ. Included among his seminary class colleagues that may have read to him were future Princeton professors George T. Purves and B. B. Warfield. William mentioned the kindness of his Princeton professors but accompanying their graciousness were difficult decisions as they adjusted the curriculum for him while maintaining fairness to those that were not so challenged. The compassionate assistance given by his classmates shows their interest in helping William so he could serve others in ministry despite his lack of vision.

All aspects of his divinity training would have required time and perseverance, but the languages must have offered particular challenges. When at the age of sixteen Louis Braille (1809-1852) was developing his method for providing written text for tactile reading, he used one to six dots in different patterns to represent each character, similar to the dots on gaming dice. Braille and other raised letter formats for the blind were available in Fentress’s day, but when he studied Hebrew he did so without a Hebrew Bible because a Braille version does not appear to have become available until after his death. William had to learn the languages by sound, auditorily and phonetically. Individuals that have studied foreign languages—especially Hebrew and Greek with their different alphabets—need only close their eyes and remember how important sight was for learning a new language. One of the difficulties novices in Hebrew face is becoming accustomed to the right to left text instead of the Western left to right orientation, but Fentress would not have been affected by the text direction because his blindness precluded that concern as readers assisted him. However, his student helpers could have spelled out words with Hebrew in his hand with their finger to assist with his understanding of the alphabet and words. Thus, even without a Braille text, he could have had some sense of the shapes of letters–maybe writing in his hand is how he learned the alphabet. Regardless of technique, the lack of vision surely inhibited his progress.

When William graduated Princeton in 1876, he had already been licensed by the Presbytery of Baltimore, April 11. It is to be noticed here that he completed studies on schedule in three years. According to his obituary by David J. Beale in The Baltimore Presbyterian, Fentress was “licensed to preach, after a full and complete examination on all the branches required, not withstanding all his disadvantages; this excites our wonder and admiration.” That is, with the challenges overcome studying without vision, William did not seek special concessions from the seminary nor had he appealed to his presbytery as an extraordinary case. For the remainder of the year he supplied Anderson Church in the Presbytery of Baltimore. In 1878 he supplied the Presbyterian Church in Stewartstown, Pennsylvania, and for three months of the same year he filled the pulpit for Rev. Johnston McGaughey of the Centre Presbyterian Church in New Park. The memorial for Fentress in the seminary’s Necrological Reports commented that he was never ordained. However, his book, Love Truths from the Bible, 1879, gives his name on the title page as “Rev. W. H. Fentress,” and his entries in Wood’s Baltimore City Directory, 1878-1880, read, “Rev. W. H. Fentress, 141 S. Sharp.” The sources do not add up but the arithmetic of historical study does not always provide a balanced equation. For a man to be ordained he had to have a call to a church, teach, be an evangelist, or serve in missions. In Fentress’s case his handicap made receiving a call difficult because congregations were concerned about the challenges they might face in having a minister that could not see. However, William had opportunities to preach in churches in Baltimore and the surrounding area as an occasional supply for vacant pulpits and ministers on vacation.

When William graduated Princeton in 1876, he had already been licensed by the Presbytery of Baltimore, April 11. It is to be noticed here that he completed studies on schedule in three years. According to his obituary by David J. Beale in The Baltimore Presbyterian, Fentress was “licensed to preach, after a full and complete examination on all the branches required, not withstanding all his disadvantages; this excites our wonder and admiration.” That is, with the challenges overcome studying without vision, William did not seek special concessions from the seminary nor had he appealed to his presbytery as an extraordinary case. For the remainder of the year he supplied Anderson Church in the Presbytery of Baltimore. In 1878 he supplied the Presbyterian Church in Stewartstown, Pennsylvania, and for three months of the same year he filled the pulpit for Rev. Johnston McGaughey of the Centre Presbyterian Church in New Park. The memorial for Fentress in the seminary’s Necrological Reports commented that he was never ordained. However, his book, Love Truths from the Bible, 1879, gives his name on the title page as “Rev. W. H. Fentress,” and his entries in Wood’s Baltimore City Directory, 1878-1880, read, “Rev. W. H. Fentress, 141 S. Sharp.” The sources do not add up but the arithmetic of historical study does not always provide a balanced equation. For a man to be ordained he had to have a call to a church, teach, be an evangelist, or serve in missions. In Fentress’s case his handicap made receiving a call difficult because congregations were concerned about the challenges they might face in having a minister that could not see. However, William had opportunities to preach in churches in Baltimore and the surrounding area as an occasional supply for vacant pulpits and ministers on vacation.

William Fentress had not enjoyed good health for much of his life and his physical strength was limited. For the last few months he suffered from “an insidious consumption,” which may have been tuberculosis or a disease with similar symptoms. He died September 4, 1880, at the age of twenty nine. Not only had he published the book of sermons mentioned previously, but he also produced a raised letter (i.e. Braille or similar) book of sermons for distribution to the blind schools of the country. It may be that the ideal call for him would have been as an evangelist ministering in a school or home for the blind. He never married and was survived by his father, brother, and sisters, but his mother died not long after he was licensed.

William Fentress had not enjoyed good health for much of his life and his physical strength was limited. For the last few months he suffered from “an insidious consumption,” which may have been tuberculosis or a disease with similar symptoms. He died September 4, 1880, at the age of twenty nine. Not only had he published the book of sermons mentioned previously, but he also produced a raised letter (i.e. Braille or similar) book of sermons for distribution to the blind schools of the country. It may be that the ideal call for him would have been as an evangelist ministering in a school or home for the blind. He never married and was survived by his father, brother, and sisters, but his mother died not long after he was licensed.

Returning to the obituary by David Beale, he said William…

was a young man of remarkable pluck and faith, that his intellect was unusually bright and vigorous, that he was a diligent and faithful student, and that he was a light in the world to those he could not see in the flesh.

William H. Fentress showed indomitable perseverance as he made his way through the educational requirements for becoming a minister. He could have appealed to his teachers and professors for concessions, but he did not do so. Some Presbyterian denominations include in their standards an extraordinary clause that allows a candidate for the ministry to request concessions for some parts of their educational requirements, but according to Beale when Fentress was licensed he asked for no concessions. William H. Fentress could have appealed to the extraordinary clause, but instead he showed himself an extraordinary man. After reading about Fentress candidates for the ministry seeking concessions through the extraordinary clause might want to reconsider.

Barry Waugh

Notes—Another Presbyterian minister of the past that faced unique struggles as he prepared for the ministry, and, like Fentress, died young is Joshua Bohannon of the Choctaw Nation. Another minister that suffered through his ministry with reoccurring health problems and an epidemic to die at a young age is “Robert Means, 1796-1836. The header of a man reading Braille and the two reading room pictures are from the online digital collection of the New York Public Library and they date to about 1900 plus or minus a decade. The issue of The Baltimore Presbyterian containing the obituary by Beale for Fentress is September 30, 1880. The full title of the series of Princeton alumni obituary books is Necrological Reports and Annual Proceedings of the Alumni Association of Princeton Theological Seminary, which are available in six volumes covering the years 1875-1932. R. Lorenzo Clark’s, History of Centre Presbyterian Church, New Park Pa., 1780-1903, Lancaster, 1903, page 34, provided information regarding Fentress’s service in that church. Thank you to Ken Henke, retired Curator of Special Collections and Archivist, Princeton Seminary, for providing several years ago copies of the portrait of Fentress and ephemera. The book, The Presbyterians of Baltimore; Their Churches and Historic Graveyards, by J. E. P. Boulden, published in Baltimore by W. K. Boyle & Son, 1875, was a helpful resource. The letter from Fentress to Howe was located in the digital scrapbook collection on the Perkins School for the Blind website, http://www.perkins.org/, on the page titled “Index to Incoming Perkins Correspondence, Volume 18, 1870-1871.” Also, for the account of another blind seminary student’s experience with biblical languages, see James C. Walker’s, “Can a Blind Man Learn Hebrew?,” The Union Seminary Magazine 19:4 (April-May 1908) 273-277.