The Presbyterian Journal was published 1959-1987 succeeding The Southern Presbyterian Journal (1942), and when The Presbyterian Guardian ceased publication in 1979 The Presbyterian Journal included in parentheses following its title (see page 2) “and Continuing The Presbyterian Guardian.” Thus, its publishing heritage included the Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS) via the Journal, and the Orthodox Presbyterian Church (OPC) via the Guardian. It was dedicated to defending and propagating the Gospel, promoting understanding of current and ecclesiastical issues by affirming Christian truth as expressed in Reformed theology directed by the infallible and inerrant Scripture, as well as applying a biblical world view to culture while serving the Triune God.

The Presbyterian Journal was published 1959-1987 succeeding The Southern Presbyterian Journal (1942), and when The Presbyterian Guardian ceased publication in 1979 The Presbyterian Journal included in parentheses following its title (see page 2) “and Continuing The Presbyterian Guardian.” Thus, its publishing heritage included the Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS) via the Journal, and the Orthodox Presbyterian Church (OPC) via the Guardian. It was dedicated to defending and propagating the Gospel, promoting understanding of current and ecclesiastical issues by affirming Christian truth as expressed in Reformed theology directed by the infallible and inerrant Scripture, as well as applying a biblical world view to culture while serving the Triune God.

The November 27, 1985 issue of Journal was dedicated to J. Gresham Machen because as the editor William S. Barker expressed it:

Those of us who are in Presbyterian denominations that require of their ministers a commitment to the inerrancy of Scripture and of their members a credible profession of faith owe a debt of gratitude—whether we realize it or not—to the subject of this week’s issue, J. Gresham Machen (1881-1937). It was Dr. Machen who, a half century ago, led in taking the stand for a doctrinally sound Presbyterian church, the stand that has now rallied increasing numbers of Christians to the truth of the Scriptures and of the Reformed faith (p. 3).

Joining Editor Barker were executive editor Joel Belz, assistant editor Stephen Lutz, and Peggy W. Everhart managed the business. When the joining and receiving of the PCA and Reformed Presbyterian Church Evangelical Synod (RPCES) was accomplished in 1982, Barker had been president of Covenant Seminary for five years but then in 1984 put on an editor’s visor to oversee Journal. He continued as editor until it ceased publication.

In the following editorial it is mentioned that personal remembrances of Machen are included earlier in the issue (pp. 6-10). Each entry is brief. Those who provided reminiscences were Paul Woolley (Westminster Seminary professor), Henry W. Coray (OPC minister), Donald C. Graham (PCA minister), Allan A. MacRae (Faith Seminary professor), R. Laird Harris (Covenant Seminary professor), Louise R. Graham (OPC missionary), Edward L. Kellogg (OPC minister), John M. L. Young (PCA minister), Harold S. Laird (PCA minister), and Lewis J. Grotenhuis (OPC minister).

I assume that Dr. Barker wrote the piece, but it may have been a collaboration with his two editorial colleagues that likely read it and advised him before the type was set. The comments in the editorial are positive and encouraging not only as the OPC anticipated its fiftieth anniversary but also as the PCA and OPC looked forward, hopefully, to becoming one church in 1986, but this would not to be the case. I would have liked to see further explanation of what is meant in the third paragraph by “lesser ideals and narrower visions were upheld” by the OPC once Machen died. This could refer to the founding of the Bible Presbyterian Church (BPC) in 1937 over issues including but not limited to premillennialism and confessional subscription. Both editors Barker and Lutz had backgrounds in the BPC, then RPCES, before becoming PCA ministers as a result of joining and receiving.

Also on Presbyterians of the Past are the following articles about the PCA 50th anniversary:

“Presbyterian Church in America, 50th Anniversary, 2023,” posted January 6, 2023, considers background information leading to the first general assembly, some of the founders of the denomination, and how the name of the denomination was selected.

“South Carolina Presbyterian History,” posted January 20, 2023, provides a list of articles on this site about Presbyterianism in the Palmetto State. If we all knew more about our Presbyterian heritage, we would be better equipped to direct the PCA according to Scripture and the Westminster Standards.

“South Florida Presbytery, 50th Anniversary of PCA,” posted February 3, 2023, tells about Daniel Iverson’s ministry founding Shenandoah Presbyterian Church in Miami, Florida, and gives history regarding the establishment of South Florida Presbytery.

“PCA 50th Anniversary, Remembering Paul Settle,” posted June 14, 2023, is a memorial for one of the founding ministers of the PCA who passed away in 2018. He was moderator of the 1984 General Assembly and a teaching elder serving in many capacities. He wrote the book celebrating the 25th anniversary.

This year, 2023, marks the fiftieth anniversary of the PCA, and it is the one-hundredth anniversary of Machen’s Christianity and Liberalism, which is quoted in the following editorial.

Barry Waugh

Editorial—Dr. Machen and True Presbyterianism

One of the characteristics of the Presbyterian Church in America as it was established in 1973 was that it was not dominated by any single leader. Nor was it founded mainly by theologians or even primarily by clergymen. It has generally been viewed as a grass-roots movement, with laymen healthily involved at every level along with ministers.

In the parallel movement for a doctrinally pure Presbyterian church a generation earlier in the North, resulting in the founding of the Orthodox Presbyterian Church whose 50th anniversary will be celebrated next year, this was not the case. Clearly the outstanding leader and spokesman for this movement was J. Gresham Machen—a New Testament scholar recognized by friend and foe alike, a lifelong bachelor, a man of godly character who was loved by his followers and often misunderstood by his opponents,

The new denomination was formed in 1936, and within less than a year he died. With the vacuum of leadership that followed, lesser ideals and narrower visions were upheld. The grass- roots following did not really materialize until the PCA developed in 1973. But to a great extent the contemporary movement for sound Presbyterianism is not well acquainted with its theological leader from an earlier generation.

One of Dr. Machen’s great gifts was to crystallize the essential issues. His Christianity and Liberalism defined the true faith over against the unbelief that passed for Christianity in the 1920s and 1930s. After a half-century, unbelief has moved on, but it is still built on the basic departures of the old liberalism which Machen saw and described so clearly.

In the earlier pages of this issue of the Journal you have been introduced to Machen the man by those who knew him personally. Here I would like to introduce you to something of his thought and style as he crystallized the issues for which we stand in his 1923, Christianity and Liberalism

With regard to the essential underlying issue:

In the sphere of religion, in particular, the present time is a time of conflict; the great redemptive religion which has always been known as Christianity is battling against a totally diverse type of religious belief, which is only the more destructive of the Christian faith because it makes use of traditional Christian terminology. This modern non-redemptive religion is called “modernism” or “liberalism.” Both names are unsatisfactory; the latter, in particular, is question-begging. The movement designated as “liberalism’’ is regarded as “liberal” only by its friends; to its opponents it seems to involve a narrow ignoring of many relevant facts.… But manifold as are the forms in which the movement appears, the root of the movement is one; the many varieties of modern liberal religion are rooted in naturalism—that is, the denial of any entrance of the creative power of God (as distinguished from the ordinary course of nature) in connection with the origin of Christianity (p. 2).

On the role of doctrine based on historical fact:

It never occurred to Paul that a gospel might be true for one man and not for another; the blight of pragmatism had never fallen upon his soul. Paul was convinced of the objective truth of the gospel message, and devotion to that truth was the great passion of his life. Christianity for Paul was not only a life, but also a doctrine, and logically the doctrine came first (p. 23). “Christ died”—that is history; “Christ died for our sins”—that is doctrine. Without these two elements, joined in an absolutely indissoluble union, there is no Christianity (p. 27). The liberal preacher is really rejecting the whole basis of Christianity, which is a religion founded not on aspirations, but on facts. Here is found the most fundamental difference between liberalism and Christianity—liberalism is altogether in the imperative mood, while Christianity begins with a triumphant indicative; liberalism appeals to man’s will while Christianity announces, first, a gracious act of God (p. 47)

With regard to Jesus Christ:

Liberalism regards him as an Example and Guide; Christianity, as a Saviour: liberalism makes Him an example for faith; Christianity, the object of faith…. But the essential thing can be put almost in a word—liberalism regards Jesus as the fairest flower of humanity; Christianity regards Him as a supernatural Person (p. 96).

On the basis for our salvation:

The modern liberal teachers persist in speaking of the sacrifice of Christ as though it was a sacrifice made by someone other than God. They speak of it as though meant that God waits coldly until a price is paid to Him before He forgives sin. As a matter of fact, it means nothing of the kind; the objection ignores that which is absolutely fundamental in the Christian doctrine of the Cross. The fundamental thing is that God Himself, and not another, makes the sacrifice for sin—God Himself in the Person of the Son who assumed our nature and died for us, God Himself in the Person of the Father who spared not His own Son but offered Him up for us all (p. 132).

Such was Dr. Machen’s expression of the basic truths upon which believing Presbyterians should unite. Charles G. Dennison, historian of the Orthodox Presbyterian Church, has made the point in New Horizons for May-June 1981 that Machen and the OPC produced not only a strict doctrine of the church, but also a countercultural position: The OPC ‘‘has no cultural or social agenda” whereas other churches, including the PCA, tend to have “strong cultural identity.”

Whether either part of that assessment is absolutely true or not, Dr. Machen’s crystallizing of the issues for Christianity in our culture, distilling the cardinal teachings of Scripture from the distortions that our culture fosters, represents an ideal that the OPC could reconfirm in the PCA. A genuine grass-roots Presbyterian movement following the leadership exemplified by Machen holds hope for the church in our time.

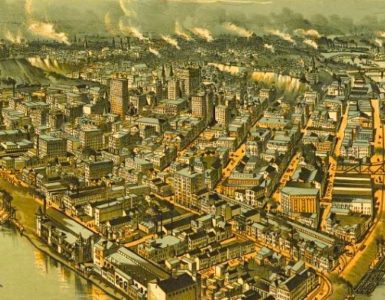

Notes—The header picture taken shows a building in Chester, England. The magazine cover picture is taken from the author’s copy and the white box obscures the original recipient’s name and address. It appears the entire run of The Presbyterian Journal is available on Internet Archive as well as its predecessor, The Southern Presbyterian Journal.