The ancestors of James Richards were from Wales. His father, also named James, was a farmer and his mother’s name was Ruth (Hanford). He was born in New Canaan, Connecticut, October 29, 1767. When he was a boy illness often limited his activity, but the physical problems did not restrain his quest for knowledge. When only thirteen years old he was a teacher at a common school for about two years. At the age of fifteen, he left home with his parents approval and lived in Newtown to apprentice with a cabinet and chair maker. However, because of his reoccurring problems with illness he returned home until recovered and then continued cabinetmaking in Danbury, Stamford, and eventually in a shop in New York.

The ancestors of James Richards were from Wales. His father, also named James, was a farmer and his mother’s name was Ruth (Hanford). He was born in New Canaan, Connecticut, October 29, 1767. When he was a boy illness often limited his activity, but the physical problems did not restrain his quest for knowledge. When only thirteen years old he was a teacher at a common school for about two years. At the age of fifteen, he left home with his parents approval and lived in Newtown to apprentice with a cabinet and chair maker. However, because of his reoccurring problems with illness he returned home until recovered and then continued cabinetmaking in Danbury, Stamford, and eventually in a shop in New York.

While growing up he was taken to worship by his parents and was instructed in Scripture at home. But as he went out on his own in the city and socialized among his peers, he went astray from the teachings of the Lord. When nineteen years old James found himself struggling as his conscience was prodded to remember Bible passages and read Scripture for guidance. He became concerned for the way he was living as the Holy Spirit illumined his understanding and he came to find assurance in Psalm 38. This psalm is penitential expressing David’s distress and confession, but also his ultimate hope in the Lord. David suffered physically, spiritually, and psychologically from the challenges he faced in his life as he endured difficult circumstances.

1 O Lord, rebuke me not in your anger,

nor discipline me in your wrath!

2 For your arrows have sunk into me,

and your hand has come down on me.

3 There is no soundness in my flesh

because of your indignation;

there is no health in my bones

because of my sin.

4 For my iniquities have gone over my head;

like a heavy burden, they are too heavy for me.

5 My wounds stink and fester

because of my foolishness,

6 I am utterly bowed down and prostrate;

all the day I go about mourning.

7 For my sides are filled with burning,

and there is no soundness in my flesh.

8 I am feeble and crushed;

I groan because of the tumult of my heart.

9 O Lord, all my longing is before you;

my sighing is not hidden from you.

10 My heart throbs; my strength fails me,

and the light of my eyes—it also has gone from me.

11 My friends and companions stand aloof from my plague,

and my nearest kin stand far off.

12 Those who seek my life lay their snares;

those who seek my hurt speak of ruin

and meditate treachery all day long.

13 But I am like a deaf man; I do not hear,

like a mute man who does not open his mouth.

14 I have become like a man who does not hear,

and in whose mouth are no rebukes.

15 But for you, O Lord, do I wait;

it is you, O Lord my God, who will answer.

16 For I said, “Only let them not rejoice over me,

who boast against me when my foot slips!”

17 For I am ready to fall,

and my pain is ever before me.

18 I confess my iniquity;

I am sorry for my sin.

19 But my foes are vigorous, they are mighty,

and many are those who hate me wrongfully.

20 Those who render me evil for good

accuse me because I follow after good.

21 Do not forsake me, O Lord!

O my God, be not far from me!

22 Make haste to help me,

O Lord, my salvation!

It is a painful psalm to read considering the agony David suffered. Derek Kidner titled his comments on this psalm, “The Outcast,” which well expresses its presentation of the thoughts of David. The shepherd-king suffered but was assured of the hope in God he had as the psalm ended, “O Lord, my salvation.” God had not abandoned him even though the great mass of evidence experienced by him seemed to the contrary. For one like James Richards who was being tempted through peer pressure, Psalm 38 expressed his distress. Remember here that James’s parents had taken him to church when he was growing up; the experience of worship—possibly including the singing of Psalm 38—provided Bible data directing him to the Gospel’s grace when he was perplexed and in trouble. The psalm, despite what might be called today negativity or too much mention of sin in fact transitioned him from the estate of sin and misery, rescued him from the miry clay, and seeded his call to the ministry. He began attending the Congregational Church in Stamford. The next step for him was to study to become a minister.

Putting aside his drawknife, mallet, and chisel along with the hazards of cuts and splinters, James Richards returned to New Canaan to pick up books for study and challenges associated with the languages of Scripture and doctrine. Pastor Justus Mitchell tutored James in preparation for college. Mitchell was the minister of his family’s church. Intellectually, James had no trouble, but his health delayed things. He became ill and later developed a disease of the eyes that prohibited reading, so his sister read to him the Bible and the volumes necessary for being ordained. The visual trouble remained for some time and when he continued studies with a minister named Burnet in Norwalk, his impairment was remedied by two kind women that read to him the required material.

By 1789, despite the factors working against success, Richards was able to enter Yale College but continued only a year due to exhausted funds. The dismal money situation resulted in his return to Burnet in Norwalk before settling in Greenfield where Timothy Dwight instructed him in college subjects and theology. Dwight was Jonathan Edwards’s grandson and had been trained by his uncle, Jonathan Edwards, Jr. At the time, Dwight was pastor of the Congregational Church in Fairfield, Connecticut, but in 1795 he became president of and a professor at Yale. Dwight’s influence at Yale was sufficient that his recommendation for Richards to receive the Bachelor of Arts was honored in 1794 even though his class attendance had been just a year.

Richards was licensed to preach the Gospel by a Committee of the Congregational Association in the Western District of Fairfield County. After supplying pulpits for varying tenures, he was invited to candidate in Morristown, New Jersey. He supplied there a few months in 1795 then was given a call that he accepted. For reasons unknown, ordination and installation were delayed until May 1797. It appears the delay was due to some division within the congregation over his call, however he was able to unite the congregation and bring peace as pastor. As he continued in Morristown, the expenses for his growing family were increasingly surpassed by his income. He asked for more salary, which many agreed should be provided but the congregation could not come to a resolution. By 1809, the family financial situation was not good, so when the minister in Newark accepted a professorship at Andover Theological Seminary and the church offered Richards a call, he accepted. During the fourteen years he served the Newark congregation, there were about five hundred new members, three hundred and thirty-two of which were added on profession of faith. Six of these new members became ministers.

Auburn Theological Seminary was established by the Synod of Geneva in 1819. Richards was appointed its professor of theology in 1820, but declined. Then three years later he accepted a new appointment and was inaugurated Professor of Christian Theology, October 29, 1823, on his fifty-sixth birthday. Auburn, as many institutions in their early years, struggled financially. In addition to teaching, by necessity Richards became a fund raiser and found out that he was a competent one. He travelled much of the state of New York, to Philadelphia, to Boston, and visited other locations raising donations with varying degrees of success. He was also what would be called today the chief financial officer. Sprague said that for Auburn Seminary, Richards was “the main spring of its financial operations.” Richards joined those of past and future that took specific positions in educational institutions only to find that their responsibilities expanded with time.

There was an item of concern at Auburn not only in the seminary but the community as well. Richards found that the views of Nathaniel Emmons were prevalent, and he worked to expose the errors as he taught classes. Richards was concerned about Emmons’s development of the New England Theology of Samuel Hopkins. Contrary to Scripture as summarized in the Westminster Standards (see Confession 6), Emmons held that only Adam was guilty of original sin and his posterity are sinners because God treats them as sinners. Further, doing right or wrong are voluntary choices and not governed by a fallen, sinful nature. Emmons’s teaching denied the imputation of Adam’s sin to his posterity. This was and is a fundamental part of doctrine. Richards was not only able to refute but influence his colleagues to change their views of Emmons without creating an argumentative environment, a skill needed to resolve controversies and maintain purity of doctrine peacefully.

There was another controversy in Auburn both in the churches and seminary. About the second quarter of the nineteenth century began an era in which revivalism used what are called New Measures. The idea was that the Holy Spirit could be excited or called to work when the conditions created by the revivalist were right. Richards believed that the measures created emotional excitement giving the appearance that, according to the New Measures interpretation, the Holy Spirit is at work. New Measures expressed a teaching developed through the New England Theology that had diminished the doctrine of sin, exalted the doctrine of man, and made the Holy Spirit one called to perform salvation when the staging was right. Using his gift for working with differing views, Richards refused to co-operate with New Measures proponents. He paid a price because he was accused by some individuals of fighting the work of the Spirit. The Auburn community and seminary were so involved in the New Measures that the students were wrapped up in the fervor and even prayed for Richards to be converted because of his opposition to New Measures. In 1740, Gilbert Tennent had published The Danger of An Unconverted Ministry as he supported revivalism, so being called an unconverted minister by his students must have given him pause, even pain, but he persisted because he knew New Measures were wrong. Sprague summarized the success of Richards’s faithful defense of the faith.

He lived not only to see the finger of scorn that had been pointed at him withdrawn, and to hear the voice of obloquy [defamation] that had been raised against him, die away, but to know that his course had met the approbation of the wise and good everywhere—to receive in some instances the hearty acknowledgments of those who had been among his active opponents.

Despite his antipathy to Emmons’s theology, James Richards became a minister in the New School in the Presbytery of Cayuga when the Presbyterians became two general assemblies in 1837 known as the Old and New Schools. One motive for the division as the Old School ejected the New was the influence of the New England Theology from Congregationalists such as Emmons and his students. Auburn Seminary was a New School seminary. From a scan of the New School General Assembly minutes, his involvement was at the first meeting in 1838 with no attendance in 1839 or 1840.

In the fall 1842, his never-vigorous constitution began an extended decline. He collapsed in the street at one point, possibly because of a stroke. He died August 2, 1843 and two days later his funeral service was held with one of his seminary colleagues, Henry Mills, leading the service. Mills went to Auburn in 1821 to be its professor of biblical criticism and oriental languages. His sermon was from Acts 13:36.

For David, after he had served his own generation by the will of God, fell to sleep, and was laid unto his fathers, and saw corruption.

Whether Mills chose a passage with David was due to his influence on Richards through Psalm 38 is not mentioned. James Richards was buried in Fort Hill Cemetery in Auburn. He was survived by his wife Carolina (Hooker) who would die at Auburn, October 8, 1847. Caroline and James had seven children. He was moderator of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA) General Assembly in 1805 where he received the gavel from James F. Armstrong and would yield it the next year to Samuel Miller. His retiring moderator’s sermon was from John 3:16-17. His successor at the podium that year was Samuel Miller. Richards was a Trustee of the College of New Jersey, 1807-1824, and a Director of Princeton Theological Seminary, 1812-1824. Among his honors were the Master of Arts from the College of New Jersey, 1801. In 1815 he was also honored with the Doctor of Divinity by Yale College and Union College. He supported the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions and in 1815 he preached the sermon at its annual gathering.

One more thought on the work of James Richards is helpful for understanding his theology. The writer is Rev. Charles Wiley, D.D., and the letter is dated August 16, 1848. The source is Sprague.

Another peculiarity of Dr. Richards—for so I think it may be regarded—was the extraordinary veneration he had for the character and intellect of President Edwards—a feeling that was ready to discover itself on all occasions, and amounted to an absorbing sentiment. No one could be in his society even for a short time, without perceiving that the writings of this eminent divine held the next place in his esteem to the Bible itself. He not only cordially agreed in the main with President Edwards in theological sentiment, (being, like him, what is technically called a mediate imputationist) but he cherished an affection for his very person and name. Again and again have I seen his eyes suffused with tears in speaking of him—tears of veneration for his piety, and of admiration and wonder at his powerful and extraordinary intellect. He did not, indeed, surrender his independence of mind even before so great a name,—for, on some minor points, he differed from Edwards; but he declared that it was always with the greatest reluctance and regret that he ventured to depart from so high an authority.

Why Wiley thought Richards’s Edwardsianism was peculiar, odd, is not noted. Since Richards was tutored for divinity almost exclusively by Dwight, it makes sense he gained high regard for Edwards which could have restrained him from the New Divinity. There are those who debate whether or not the seeds of the New England Theology were planted by Edwards and cultivated by his students, so maybe they have a solution for both Wiley’s comments and Richards’s admiration for Edwards.

Barry Waugh

Several of Richards publications are available for convenient PDF download on the Log College Press website at “JAMES RICHARDS, 1767-1843.” The following is a list of Dr. Richards’ publications:—A Discourse Occasioned by the Death of Lewis Le Conte Congar, a Member of the Theological Seminary at Andover, 1810. An Address Delivered at the Funeral of Mrs. Sarah Gumming, Wife of the Rev. Hooper Gumming, 1812. Two Sermons in the New Jersey Preacher: or, Sermons on Plain and Practical Subjects, ed. Samuel S. Smith, Vol. 1, 1813, “On Attending the public worship of God,” Ecclesiastes 5:1, pp. 89-104, and “The Danger and Folly of Indulging a Covetous Temper,” Luke 12:20, pp. 187-199. A Sermon Before the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign missions, 1814. A Sermon at the Funeral of Deacon Stephen Baldwin, 1816. “This World is Not Our Rest,” A Sermon Delivered at Morristown, 1816. The Sinner’s Inability to Come to Christ: A Sermon on John 6:44, 1816. A Circular on the Subject of the Education Society of the Presbyterian Church in the United States, 1819. A Sermon before the Education Society of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, 1819. A Sermon on a day of Public Thanksgiving and Prayer, 1823. Two Lectures on the Prayer of Faith, Read before the Students of the Theological Seminary at Auburn, 1832. Two Sermons in the National Preacher, 1834. After Dr. Richards’ death there was published from his manuscripts in 1846, in an octavo volume, Lectures on Mental Philosophy and Theology, with a sketch of his life, by Samuel H. Gridley; Sermons by the Late Reverend James Richards, D.D.: With an Essay on His Character by William B. Sprague, D.D., Albany, 1849, is a collection of twenty sermons.

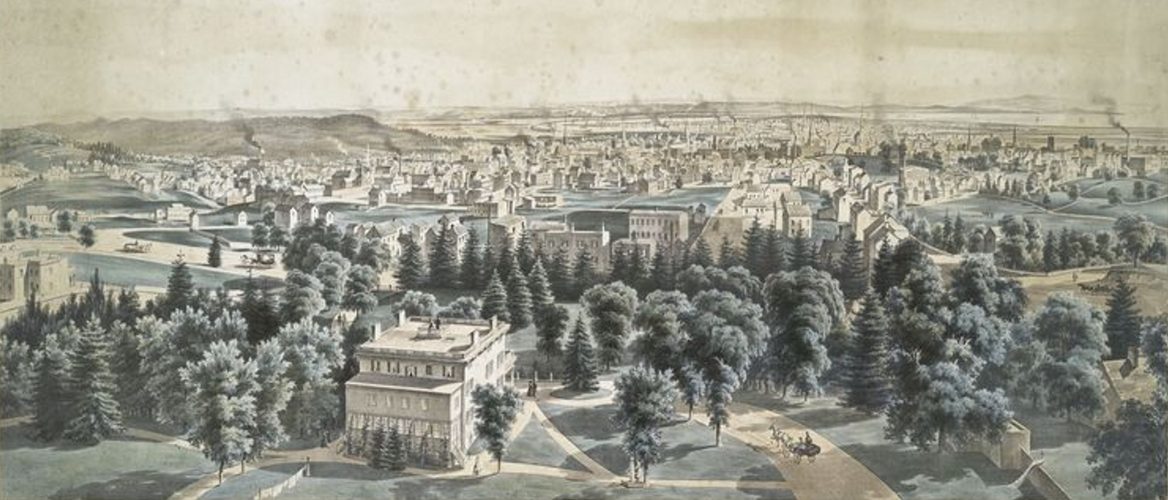

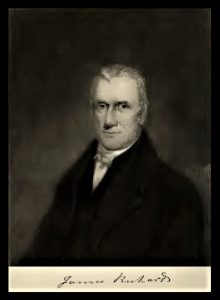

Notes—The header is from the New York Public Library Digital Collection and is titled, “Newark, N.J. from the residence of T.V. Johnson, Esqr.” In the 1920s the Auburn Declaration would be important for the Fundamentalist-Modernist Controversy and lead to the founding of the Orthodox Presbyterian Church and Westminster Theological Seminary. The portrait is from Richards’s book, Lectures on Mental Philosophy. Gilbert Tennent’s sermon is, The Danger of an Unconverted Ministry: Considered in a Sermon on Mark VI. 34, Philadelphia: Printed by Benjamin Franklin, in Market-street, 1740. Sprague refers to William B. Sprague, Annals of the American Pulpit, volume 4. Some biographical information is from the biography by Gridley in Richards’s Lectures on Mental Philosophy and Theology. Also consulted, was A History of Auburn Theological Seminary, 1818-1918, written by the librarian, John Quincy Adams [I wonder who he was named for?], and published by Auburn Seminary Press, 1918; this book includes within its information biographies of faculty and others along with their portraits.