Charles Allen was born to James and Mary Stillman in Charleston, South Carolina, March 14, 1819. He attended Oglethorpe University before earning his theological degree from Columbia Seminary in 1844. He was licensed by Charleston Presbytery later that year. Second Presbyterian Church of Charleston gave young Stillman the opportunity to supply its pulpit while pastor Thomas Smyth was in Europe for an extended trip. From Charleston, Stillman’s first call took him to the Mesopotamia Presbyterian Church (named First Church by 1851) in Eutaw, Alabama. In preparation for his new ministry, Stillman and the congregation were exhorted by Tuscaloosa Presbytery to have a day of prayer and fasting the Friday before his ordination and installation service. Remaining in Alabama, he next served the Gainesville church for seventeen years before moving in 1870 to First Church, Tuscaloosa. According to George Howe, First Church was founded by Robert M. Cunningham and it is believed he encouraged a group of South Carolinians from the Pendleton District to settle along the Black Warrior River with the hope of new and better opportunities as Tuscaloosa grew. Tuscaloosa had been the third Alabama capital until 1846 when the capital was moved to Montgomery. Thus, by the time Stillman became minister of First Church, the city had suffered a population loss due to relocation of the state government, been through the Civil War including Federals burning the university campus, and been under Reconstruction for five years. He continued a successful and busy ministry not only in Tuscaloosa but also in the greater denomination until he died January 23, 1895. The University of Alabama gave him the Doctor of Divinity in 1863.

Charles Allen was born to James and Mary Stillman in Charleston, South Carolina, March 14, 1819. He attended Oglethorpe University before earning his theological degree from Columbia Seminary in 1844. He was licensed by Charleston Presbytery later that year. Second Presbyterian Church of Charleston gave young Stillman the opportunity to supply its pulpit while pastor Thomas Smyth was in Europe for an extended trip. From Charleston, Stillman’s first call took him to the Mesopotamia Presbyterian Church (named First Church by 1851) in Eutaw, Alabama. In preparation for his new ministry, Stillman and the congregation were exhorted by Tuscaloosa Presbytery to have a day of prayer and fasting the Friday before his ordination and installation service. Remaining in Alabama, he next served the Gainesville church for seventeen years before moving in 1870 to First Church, Tuscaloosa. According to George Howe, First Church was founded by Robert M. Cunningham and it is believed he encouraged a group of South Carolinians from the Pendleton District to settle along the Black Warrior River with the hope of new and better opportunities as Tuscaloosa grew. Tuscaloosa had been the third Alabama capital until 1846 when the capital was moved to Montgomery. Thus, by the time Stillman became minister of First Church, the city had suffered a population loss due to relocation of the state government, been through the Civil War including Federals burning the university campus, and been under Reconstruction for five years. He continued a successful and busy ministry not only in Tuscaloosa but also in the greater denomination until he died January 23, 1895. The University of Alabama gave him the Doctor of Divinity in 1863.

Dr. Stillman’s connectional ministerial efforts in presbytery, synod, and general assembly were many. He was the Chairman of Tuscaloosa Presbytery’s Home Missions Committee for a number of years. From 1847 until 1884 he was stated clerk of Tuscaloosa Presbytery. In 1869, Stillman and D. D. Sanderson made a six-week trip through the counties of Blount and Jefferson (Birmingham) spying out the land and concluded the region was ripe unto harvest for mission work. Likely, his most significant achievement beyond his pastoral work was his uniting with a group of Tuscaloosa Presbyterians to present an overture to the 1875 General Assembly proposing establishment of a training school for black ministers. The proposal was controversial with vocal opponents but a committee was appointed to report to the Assembly the next year. The committee’s recommendation to establish a school was adopted and the new facility was named the Institute for Training Colored Ministers at Tuscaloosa and Stillman was made its superintendent. In the fall of 1876, he began teaching classes in the Institute but due to his duties at First Church he was not able to spend as much time teaching as he would have liked, so much of the daily work was done by Andrew F. Dickson (though for a brief stint). The Institute came to be named the Stillman Institute to honor its devoted founder who was superintendent until his death. The curriculum as well as the Institute’s name have changed over the years; it is currently known as Stillman College.

One of Dr. Stillman’s privileges as a minister of the PCUS was his selection to moderate the General Assembly when it convened in First Church, New Orleans, May 17, 1877. Retiring moderator B. M. Smith had delivered his sermon from Luke 11:13 and John 16:8-11 before Stillman’s election. Items that came before him included a request from the Synod of Alabama for a definition of the duties of the deacons and sessions. Note here that the Book of Church Order was not yet complete.

The duties of the Deacons, as servants (Ministers) of the Church, are to execute the orders of the Session (or Parochial Presbytery) as rulers of the Church. Therefore, it is the duty of the Deacons to collect and appropriate all funds for church purposes, whether for local purposes, support of a pastor, aid to the poor, and expenses of the church, or for objects of Christian benevolence recognized in the action of the courts of the Church, under the direction of the Church Session.

Not all that occurred at Assembly meetings was strictly business. It was customary for local organizations, institutions, and businesses to invite the commissioners for special events. A communication was received from the commander of the steamer Robert E. Lee offering a free excursion on the Mississippi River at five o’clock one afternoon. The offer was accepted, the cruise accomplished, and the Assembly gave “cordial and thankful acknowledgment of the courtesy.” An issue that often came up during assembly meetings in the nineteenth century was the subject of worldly amusements. Among these amusements were games of chance, card playing, dancing, hanging out at firehouses (apparently a questionable social hub of the era), and attending the theater. An overture from the Presbytery of Atlanta asked the Assembly to interpret “the law of the Church concerning worldly amusements, as set forth in the deliverances of the Assemblies of 1865 and 1869,” with the presbytery’s specific concerns expressed in the following questions that were directed to a specially appointed committee.

1st, Does the law [Law] forbid card-playing for purposes of amusement, or only for purposes of gambling?

2nd, Does it forbid dancing, or only promiscuous dancing?

3rd, If the latter only, to what does the word “promiscuous” refer?

4th, Does the law forbid round dances merely, as distinguished from the square? or dancing at a public ball, as distinguished from dancing in a private house? or the mingling of males and females in this amusement for the reason among others, that in such cases the dance has a tendency to influence the licentious passions.”

The committee’s report was adopted as amended by the Assembly and reads as follows.

Answer 1st. The Assembly has uniformly discouraged and condemned the modern dance in all its forms, as tending to evil, whether practiced in public balls or in private parlors.

2d. Some forms of this amusement are more mischievous than others; the round dance than the square, the public ball than the private parlor, but all are evil and should be discountenanced.

3d. The extent of the mischief done depends largely upon circumstances. The church session is therefore the only court competent to judge what remedy to apply; but the Assembly being persuaded that in most cases it is the result of thoughtlessness or ignorance, recommends great patience in dealing with those who offend in this way.

4th. The following was added by the Assembly as an amendment: And we further affectionately urge all our Christian parents not to send their children to dancing schools, where they acquire a fondness and an aptitude for this dangerous amusement.

If the General Assembly of 1877 was transported through time and provided its assessment of the current situation it would surely be aghast. Such statements about piety by Presbyterians of the past are often scoffed at as deliverances about things that do not really matter, but do Christians become desensitized over time as the world works successfully to squeeze them into its mold? The word promiscuous was mentioned. Is the word used anymore or has it become one of those supposedly judgmental terms caricatured as one entity imposing its opinion on another? There is such a thing as promiscuity.

Additional business before Moderator Stillman included dealing with The General Council of the Presbyterian Alliance which was scheduled to meet in 1880 in Philadelphia. Several PCUS presbyters had been appointed to attend but some of them declined. Stillman was elected to fill one of the vacated positions. The Report of Stillman Institute came through the Christian Education Committee which had its recommendations adopted. The committee commented “That the attention of the churches be directed to the Institution for the education of the colored candidates for the ministry, under the care of Dr. Stillman and Prof. A. F. Dickson, and that they be called upon to aid generously in its support.” A committee was appointed to oversee the Institute and include in its report to the next Assembly “a complete constitution and by-laws for itself, and for the institution over which it is to be placed.” The first report of the Institute was composed by Stillman and it listed the curriculum which used Truths for the People by William S. Plumer for the school’s introductory theology lessons. The PCUS was continuing to expand its bounds as exemplified by an overture from the Presbytery of Florida requesting establishment of the Synod of Florida. The Assembly declined the request because sufficient information was not provided, and it instructed the Presbytery of Florida to first approach the synods of Georgia and Alabama where application for a new synod should begin (Synod of Alabama included the Florida panhandle). Possibly, the failure of the Presbytery of Florida to follow proper procedure was a result of the yet to be completed Book of Church Order; it is difficult to follow procedures when procedures are not adopted, published, and subscribed to. More changes were sent down to presbyteries with the instruction to vote on adopting “the whole book.” The Assembly adjourned Saturday evening May 26 after seven days of business and two Sabbaths.

Charles Stillman was married three times. He married Martha Hammond of Milledgeville, Georgia, October 15, 1846. His second marriage was April 17, 1866 to widow Fannie Collins of Shubuta, Mississippi. His last spouse was Elfreda Walker of Clarksville, Tennessee, and they were married April 17, 1872. At least two of Dr. Stillman’s descendants continued to serve the Presbyterian Church–his daughter, Anna M. Stillman, was a secretary for Rev. T. P. Mordecai at the First Presbyterian Church, in Birmingham, Alabama, and his grandson, Rev. Charles Sholl, was the pastor of the Avondale Presbyterian Church, another of the Presbyterian churches in Birmingham.

Dr. Stillman’s publications are limited but include: The entries “The Pulpit and the Pastorate,” 84-95, “Biographical Sketch of William Curdy Emerson,” 268, and “Biographical Sketch of William Inge Hogan,” 290-91, in Memorial Volume of the Semi-Centennial of the Theological Seminary at Columbia, South Carolina, 1884. His pamphlets, “Sprinkling and Pouring, Scriptural Modes of Baptism: A Sermon Preached by Order of the Presbytery of Tuscaloosa, and Published by their Request, 1859; The Dead of the Synod of Alabama, Presbyterian Church U. S. from 1862 to 1890, 1891; “The Death of the Righteous. A sermon Preached in the Presbyterian Church at Gainesville, Alabama, on Sunday, December 23, 1855, on Occasion of the Death of Dr. Anson Brackett,” 1856; “A Discourse Delivered in the Baptist Church, Carlowville, Alabama, by Rev. Charles A. Stillman, Pastor of the Presbyterian Church, Eutaw, Alabama,” 1848; in the Southern Presbyterian Review are found “Success in the Ministry,” 17:1 (July 1855), “The Benefits of Infant Baptism,” 17:2 (Sept. 1866), and “Giving, an Essential Part of True Piety,” 21:4 (Oct. 1870); and “The Birmingham Conference,” in The Presbyterian Quarterly 8.2 (April 1894) 272-276.

Barry Waugh

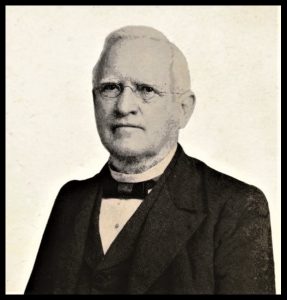

Sources—the header map of New Orleans is from the Library of Congress digital collection. First Church is at the upper left corner of Lafayette Square which is marked by the red ellipse, but the building burned in 1854, so the one where GA assembled was different. The portrait is edited from one on the cover of The Pulpit and the Pastorate, by Stillman as published by Log College Press. Helpful for those with map interests are “Map of the Black Warrior River from Tuscaloosa to the Fork of Sipsey and Mulberry,” 1879, which shows Tuscaloosa city limits, then the University of Alabama, and then the Insane Asylum along the river, while the 1887 “Perspective Map of Tuskaloosa [sic], Alabama,” provides a nice picture of the city and both are available from the digital collections of the Alabama Department of Archives and History. For Howe on Tuscaloosa see vol. 2, History of the Presbyterian Church in South Carolina, page 649. Information was located in H. A. White, Southern Presbyterian Leaders, 1683-1911, Banner of Truth, 2000; James W. Marshall as edited by Robert Strong, The Presbyterian Church in Alabama, The Presbyterian Historical Society of Alabama, 1977; Scott, Ministerial Directory of the Presbyterian Church, U.S., 1861-1941, 1942; Nevin, Presbyterian Encyclopedia, 1884; assorted Minutes of the General Assembly of the P.C.U.S., and the Stillman College website. The nearly 1200 pages of proceedings of The General Council of the Presbyterian Alliance of 1880 is available online.