There must be some difficult situations and decisions to be made when a minister of the church is employed by the government to serve as a chaplain. Such a calling would be similar to serving in a state church because the responsibilities of church and state may become entangled. History bears witness to the fact that monarchs governing churches expected their clerics to submit to their will just as though they were civil officials. A clear though not unique example of the problem is England’s Henry VIII whose desire for a male heir to the throne clouded his judgment concerning the church, and as the years passed he required his clergy to yield to his wishes not only for political but also personal ends. Church and state issues have been and will continue to be sticky wickets. Thus, serving as a penitentiary chaplain, which is a pastoral ministry to parishioners behind bars, had to have been a rough job in the nineteenth century. Despite the challenges and church-state tensions of the chaplaincy, John L. Milligan worked in the Western State Penitentiary in Pennsylvania for forty years.

There must be some difficult situations and decisions to be made when a minister of the church is employed by the government to serve as a chaplain. Such a calling would be similar to serving in a state church because the responsibilities of church and state may become entangled. History bears witness to the fact that monarchs governing churches expected their clerics to submit to their will just as though they were civil officials. A clear though not unique example of the problem is England’s Henry VIII whose desire for a male heir to the throne clouded his judgment concerning the church, and as the years passed he required his clergy to yield to his wishes not only for political but also personal ends. Church and state issues have been and will continue to be sticky wickets. Thus, serving as a penitentiary chaplain, which is a pastoral ministry to parishioners behind bars, had to have been a rough job in the nineteenth century. Despite the challenges and church-state tensions of the chaplaincy, John L. Milligan worked in the Western State Penitentiary in Pennsylvania for forty years.

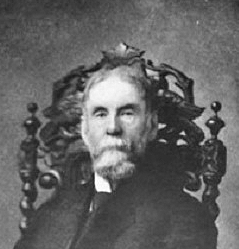

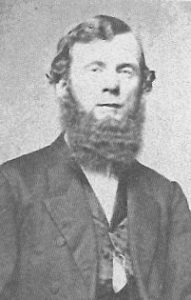

John Lynn was born to James and Eleanor (Lynn) Milligan, July 31, 1837, in Ickesburg, Pennsylvania, which is about forty miles northwest of Harrisburg. His early education was obtained under the mastership of Mr. J. H. Shoemaker in Tuscarora Academy. John professed faith in Christ while a college student. He continued his studies in Washington College graduating with the class of 1860. In the fall he entered Princeton Theological Seminary where he completed the program in 1863 after having been licensed by the Presbytery of Huntington in the Synod of Philadelphia, Old School, in April of the previous year. He was particularly adept at languages and at the time of his death he read and spoke Spanish, French, Italian, and German with ease, and as one might expect of a minister of the day, he read Greek and Hebrew, to which he added Arabic. One of his seminary friends, James B. Kennedy, kept an autograph book in which his classmates could write sentiments, sign their autographs, and adhere photographs. Milligan concluded his comments to his friend and fellow Pennsylvanian with the following paragraph.

Soon we must part from this elevation of sacred learning. We both return to Pennsylvania. May we do nothing ever to tarnish her fair fame, and in our life work, the noblest and most responsible of all callings, may we “be heroes in the strife”—“quit ourselves like men” and having done all acquitted, accepted, and glorified with our Captain in heaven.

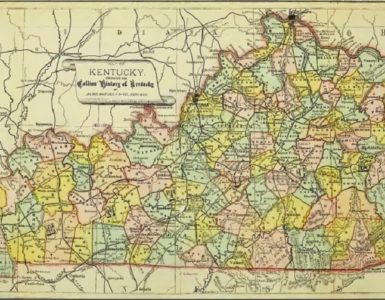

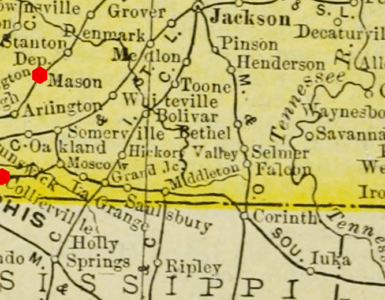

Before he sought a call to a church, Licentiate Milligan entered the Civil War first as a volunteer with an agency of the YMCA for three months, then as a chaplain from November 1863  through May 31, 1865. His first church pastoral call was to the First Presbyterian Church in Horicon, Wisconsin, where he was ordained and installed February 21, 1866. However, within a few years a friend who was a deputy in the Western State Penitentiary in Pennsylvania recommended Rev. Milligan to his employer for the prison’s vacant chaplaincy. He initially refused the opportunity, but persistence from his friend and others led him to accept the position. However, the transition was slowed by the unwillingness of the Presbytery of Winnebago to accept his resignation from his call because it believed he was sorely needed in Wisconsin because of a shortage of ministers. However, persistence achieved its end on January 15, 1869, when his call was dissolved by presbytery freeing him to move to Allegheny, which is currently part of Pittsburgh.

through May 31, 1865. His first church pastoral call was to the First Presbyterian Church in Horicon, Wisconsin, where he was ordained and installed February 21, 1866. However, within a few years a friend who was a deputy in the Western State Penitentiary in Pennsylvania recommended Rev. Milligan to his employer for the prison’s vacant chaplaincy. He initially refused the opportunity, but persistence from his friend and others led him to accept the position. However, the transition was slowed by the unwillingness of the Presbytery of Winnebago to accept his resignation from his call because it believed he was sorely needed in Wisconsin because of a shortage of ministers. However, persistence achieved its end on January 15, 1869, when his call was dissolved by presbytery freeing him to move to Allegheny, which is currently part of Pittsburgh.

Rev. Milligan moved back to his home state to begin his work. Western State Penitentiary was established early in the nineteenth century with its first prisoner arriving in July 1826. As the years passed, the capacity was exceeded and prison practices were changing, so a new property was acquired in 1878 where a larger facility reflecting current design philosophy was constructed. Some of the difficulties faced by him during his years included in 1886 the attack of three prison officials by an inmate, one of the men died from his stabbing wounds, but the other two survived. In 1885, nearly four hundred prisoners became ill with influenza during an epidemic. In 1884, there was a flood which inundated Western Penitentiary as the waters of the Ohio River rose. In March 1902 the prison was again flooded such that the New York Times described Allegheny as “a modern Venice, with every sort of improvised water craft in service.” The water problems were such that when Chaplain Milligan resigned, his successor suggested to the prison administration that the reoccurring floods necessitated construction of a new facility. Added to these episodes of difficulty were changes in wardens; new laws, both state and federal; the change of penal philosophy from penitence, penitentiary, to behavior modification, correctional center; and capital punishment was debated in the 1890s because of efforts to move executions from local jails to the penitentiaries of Pennsylvania.

The National Prison Association (NPA) was organized in 1870 with Chaplain Milligan a charter member, and he later became its secretary continuing until his retirement from office in 1908. When the association held its annual meeting in Pittsburgh in 1891, a special Sunday evening lecture was held in the Duquesne Theater on Penn Avenue. The speaker, Dr. T. K. Beecher, was one of the several famous–or infamous depending on one’s perspective–children of the New School Presbyterian minister, Dr. Lyman Beecher. Milligan was seated on the platform with former U. S. President Rutherford B. Hayes, who was an active member of the NPA for several years, and other officers and dignitaries committed to the association’s work. A reporter for The Pittsburgh Dispatch, October 12, commented that Beecher’s two hour lecture “pursued his theme in a rather erratic way, and continually left the thread of his argument, if such it could be called, to follow out a train of thought suggested by the moment.” The reporter concluded his thoughts about the lecture saying, “He was listened to throughout with much attention,” which surely must have been a concession to Victorian courtesy or a tongue in cheek comment given his critique of Beecher’s discourse. One can only imagine the uncomfortable evening as the august folks wriggled in their seats on the platform visible to all while bearing an appearance of attentiveness. The Duquesne Theater was being used by the congregation of Christ’s Church for its weekly services and it had allowed the NPA to hold its meeting that evening with them resulting in a greatly overcrowded situation. Chaplain Milligan continued a faithful member of the NPA until his life of service was capped by his election to the organization’s presidency in 1908.

Other aspects of his work associated with the penitentiary included his charter membership in the Allegheny County Prison Society which included some years as its president. He was selected the representative of the United States at the International Prison Congress during its meetings in London in 1872, Stockholm in 1878, Rome in 1885, St. Petersburg in 1890, Paris in 1895, and Budapest in 1905. One aspect of his work with the Executive Committee of the NPA was reported in The Pittsburgh Dispatch, February 14, 1892. It involved a proposal to ship all the prisoners of the United States to Alaska with a headquarters in Sitka which would govern the area as a penal colony. Rev. Milligan pointed out that he believed both England’s attempt at a penal colony in Australia and France’s Devil’s Island off the coast of French Guiana failed. Chaplain Milligan commented, “I don’t believe in sending criminals to islands.”

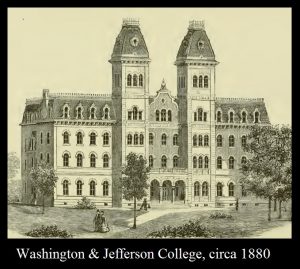

John Milligan was also active in the Presbytery of Allegheny. He was its stated clerk from 1882 until 1906 when it was consolidated with Pittsburgh Presbytery. The new presbytery elected him the first moderator. In 1892, he participated in services dedicating the new Providence Presbyterian Church building in Allegheny. The morning service that day included a sermon preached by Dr. James D. Moffatt, the president of Washington and Jefferson College; Scripture was read by Rev. Samuel M. Mackay; prayer was offered by Dr. Robert Dick Wilson; and Providence’s pastor, Rev. William A. Kinter, provided the invocation. Rev. Milligan’s contribution was prayer in the evening service. In commemoration of his many years of service his fellow ministers presented him with a handsome trophy with their names and all their churches engraved on it.

John Milligan was also active in the Presbytery of Allegheny. He was its stated clerk from 1882 until 1906 when it was consolidated with Pittsburgh Presbytery. The new presbytery elected him the first moderator. In 1892, he participated in services dedicating the new Providence Presbyterian Church building in Allegheny. The morning service that day included a sermon preached by Dr. James D. Moffatt, the president of Washington and Jefferson College; Scripture was read by Rev. Samuel M. Mackay; prayer was offered by Dr. Robert Dick Wilson; and Providence’s pastor, Rev. William A. Kinter, provided the invocation. Rev. Milligan’s contribution was prayer in the evening service. In commemoration of his many years of service his fellow ministers presented him with a handsome trophy with their names and all their churches engraved on it.

He continued his chaplaincy in Western State Penitentiary until June 1909, when he was made chaplain emeritus, owing to his incapacity to fill the duties on account of ill health. He had been preaching in the penitentiary chapel on January 17, 1909, and suffered an “apoplectic stroke,” that resulted in his death later on July 12 in Newport in the home of his sister, Clara Ellen (or Eleanor), and her husband, John Holmes Irwin. He was also survived by his brother, Thomas, who had operated a hardware business in Newport for many years. Another surviving sibling was Ann, who was married to H. O. Orris, M.D. Chaplain Milligan never married. Among the many tributes at his graveside was a wreath of galix leaves, palms, and carnations from the prisoners of the Western Penitentiary. The impression one gets when reading sources about Rev. Milligan is that he was one of those people that was liked by all who made his acquaintance. One anonymous author commented that “among the greatest of all his endowments was his power to inspire affection.” Rev. John Lynn Milligan, Presbyterian chaplain and stated clerk, and prison reformer was buried in the Newport Cemetery in Perry County.

In conclusion, it is unfortunate that a more panoramic picture of the life and ministry of J. L. Milligan cannot be painted with the sources consulted; the scene presented is missing the central vista of his life, forty years of pastoral work to those behind bars. His family background, education, denominational work, and involvement in professional organizations provide some views, but the forty years of leading prisoners in worship, counseling with them, and teaching the Bible are missing. Maybe there is in an archive holding a journal of his life that could provide material for a more complete picture. The impression left is that he was a stated clerk and a prison reformer, but how he ministered to and cared for his parishioners behind bars is, sadly, limited to the flowers of mourning given to cover his grave.

BARRY WAUGH

Notes—Some sources spell his middle name “Linn,” but in papers he signed he has written his name “J. Lynn Milligan” and it is written on his grave marker the same way. The information regarding the new facility for the Western Penitentiary built circa 1878 is conflicting and it is hard to believe that the new prison was completed in less than a year given its size. One source gave the date of completion as 1882, which seems more likely. Pictures of his grave in Newport are available on Find-a-Grave. Over the years, the city of “Pittsburgh” has been spelled “Pittsburg,” and vice versa, just do searches of the web with both spellings. For some trivia see http://www.visitpittsburgh.com/about-pittsburgh/history/the-pittsburgh-h/ which explains the history of the spellings with and without the final “h”.

Sources—The portrait of Milligan with his lengthy beard, which is on the page he wrote for Kennedy’s sentiment book, was taken on or before April 1863 and a copy was graciously provided by Ken Henke, Curator of Special Collections and Archivist, Princeton Seminary, who also provided copies of several press obituaries and seminary alumni forms. From The New York Times archives online, the flooding in 1884 is located in the issues of February 2, 8, 6, 9, 11, and 13; the attack on prison officials by an inmate is from the issue of Feb. 5, 1886; and the 1902 flood account was found in the issue of March 2. The information on the influenza epidemic is from, State Prisons, Hospitals, Soldiers’ Homes and Orphan Schools Controlled by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, by Amos H. Mylin, Vol. 1, Clarence M. Busch, State Printer of Pennsylvania, 1897. The Princeton Seminary Necrological Report for Milligan was a source along with assorted memorials in publications associated with his prison reform work and professional organizations. The Moffat and Washington and Jefferson College images are from Nevin’s encyclopedia.

A Note on Washington College, Jefferson College, and Washington and Jefferson College—Washington and Jefferson College was established by an act of the Pennsylvania Legislature March 4, 1865. John Milligan would not have had classes in the building pictured in this biography because he attended Washington when it was a separate school, but he did receive his LL.D. from the two institutions united in Washington and Jefferson. The two schools had merged and attempted to conduct some classes on the old Jefferson campus in Canonsburg with others on the Washington campus in Washington. It did not work. On February 26, 1869, the campus was consolidated at the Washington location but not to the satisfaction of all individuals. There was adjudication that went to the state and federal supreme courts. Finally, the building pictured was constructed for a new beginning for Washington and Jefferson College in Washington. Canonsburg and Washington are just under ten miles apart and as the years passed with speedier and more accessible transportation, the colleges that had once seemed a good distance apart were merely a hop, skip, and a jump away. Thus, many colleges merged in the late nineteenth century and into the twentieth.