According to Bradley J. Gundlach’s Process and Providence: The Evolution Question at Princeton, 1845-1929, the scientific and evolutionary differences in views between Charles Hodge of Princeton Seminary and President James McCosh of Princeton College have been overstated sufficiently to obscure the institutions’ theological and philosophical affinities. The author also uses “Princeton” as an encompassing term for both the college and seminary, particularly during the Charles Hodge era. The two institutions were bonded by a Presbyterian-Reformed theological commitment as presented in the Westminster Standards and the philosophical use of Scottish common-sense realism, but as the years passed the institutions’ boards and faculties diverged in thought. In keeping with their similar views during the early years, the author sometimes uses “Princeton” in a way that obscures whether he is referring to the college or seminary—but then maybe the ambiguity was intended to show how close the two schools were in thought early on. An example of their close relationship is that Charles Hodge was president of the college board of trustees when McCosh was called to Princeton, but at the time of his hiring he had not adopted his Darwin-based view. It seems the sea trip from Ireland to the United States rocked McCosh’s perspective enough to persuade him that dropping anchor in the port of Darwin was a safe haven. Those individuals in Princeton, particularly in the college, who to one degree or another espoused evolution now had a sympathetic leader.

According to Bradley J. Gundlach’s Process and Providence: The Evolution Question at Princeton, 1845-1929, the scientific and evolutionary differences in views between Charles Hodge of Princeton Seminary and President James McCosh of Princeton College have been overstated sufficiently to obscure the institutions’ theological and philosophical affinities. The author also uses “Princeton” as an encompassing term for both the college and seminary, particularly during the Charles Hodge era. The two institutions were bonded by a Presbyterian-Reformed theological commitment as presented in the Westminster Standards and the philosophical use of Scottish common-sense realism, but as the years passed the institutions’ boards and faculties diverged in thought. In keeping with their similar views during the early years, the author sometimes uses “Princeton” in a way that obscures whether he is referring to the college or seminary—but then maybe the ambiguity was intended to show how close the two schools were in thought early on. An example of their close relationship is that Charles Hodge was president of the college board of trustees when McCosh was called to Princeton, but at the time of his hiring he had not adopted his Darwin-based view. It seems the sea trip from Ireland to the United States rocked McCosh’s perspective enough to persuade him that dropping anchor in the port of Darwin was a safe haven. Those individuals in Princeton, particularly in the college, who to one degree or another espoused evolution now had a sympathetic leader.

As Dr. Gundlach develops his case he brings into his narrative the college and seminary personnel of later years. In the seminary the individuals noted, among others, move from Charles Hodge, to A. A. Hodge, then to C. W. Hodge, on to B. B. Warfield, and finally J. Gresham Machen. The key figures are analyzed with objectivity as the author works through primary and secondary sources to show that the fences built by historical theologians between the views of thinkers of the past are not always board and batten but rather in some cases are more like chain link. Despite the author’s historical objectivity, I came away with the impression—a subjective assessment from reading between the lines–that he did not care much for Francis L. Patton. As the controversies of the 1920s dawned, Dr. Gundlach assessed that the appeal of B. B. Warfield and J. Gresham Machen to the fundamentalist movement was their theological supernaturalism. Warfield could be relied on for his defense of the God-breathed Word, and Machen, also holding a theopneustosic view, became the voice of the supernatural for the virgin birth, the message of Paul, and Gundlach’s selection for emphasizing Machen, Christianity and Liberalism. The gist of Dr. Gundlach’s analysis is that the period of his study was unified in thought from Alexander through Machen by its defense of supernaturalism with the help of common sense realism against the reoccurring manifestations of naturalism, whether it was the deism of the early days or the theological liberalism (evangelicalism?) of the later years. Fundamentalists did not accept Princeton’s views on science and evolution, but if the issue of debate involved the supernatural outside the context of creation and origins, fundamentalism and Princeton could get along in a common cause. I find this analysis beneficial and well thought out except for one thing—the author did not adequately address the fact that Princeton’s supernaturalist perspective was delimited by the Westminster Standards‘ interpretation of the Bible; he mentioned that the Princetonians subscribed to the Standards but did not develop how their summary of doctrine affected their thinking.

The important work of Mark Noll and others has provided insight into the philosophical influence of common-sense realism at Princeton, but supernaturalism is essentially a theological issue. After all, super-nature is beyond nature, it acts in, through, or upon nature. Supernatural is necessarily the work of the Triune God and theology is the proper subject for providing understanding of the supernatural. For the Presbyterian Princetonians who dominated the leadership, administration, and faculty of both Princeton institutions, their theology was summarized and delimited by the Westminster Standards. For example, even though Charles Hodge and McCosh differed on evolution, they agreed theologically as subscribers to the Westminster Standards. Confessionalism summarily expressed the Bible’s supernaturalism. The first section of chapter one on the Word of God in the Westminster Confession of Faith expresses the supernatural nature of Scripture as God’s revelation.

Although the light of nature, and the works of creation and providence, do so far manifest the goodness, wisdom, and power of God, as to leave men inexcusable; yet they are not sufficient to give that knowledge of God, and of his will, which is necessary unto salvation: therefore it pleased the Lord, at sundry times, and in divers manners, to reveal himself, and to declare his will unto his Church; and afterwards, for the better preserving and propagating of the truth, and for the more sure establishment and comfort of the Church against the corruption of the flesh, and the malice of Satan and of the world, to commit the same wholly unto writing; which maketh the holy scripture to be most necessary; those former ways of God’s revealing his will unto his people being now ceased.

The light of nature cannot bring individuals to the knowledge of God’s will sufficiently for understanding salvation, nor does it tell us all God has revealed regarding himself. The light of nature was created by God and is thus a product of his supernatural work. The first words of the Confession bring out the natural vs. supernatural theme running throughout Scripture which was adopted with vigor and taught with clarity in Princeton’s history. The given facts of Scottish common-sense realism are compatible with supernaturalism, but the supernatural is defined and worked out by God as revealed in his Word and summarily comprehended in the Westminster Standards.

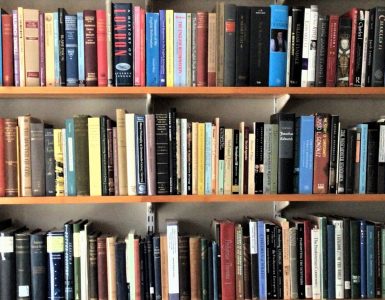

Despite my point of contention regarding confessionalism, Dr. Gundlach’s book is thoroughly researched with primary and secondary sources, well written, and insightful. It should be read along with the work of Mark Noll, David B. Calhoun, D. G. Hart, W. K. Selden, and others to understand the complexities of Princeton Seminary and University, 1845-1929. Process and Providence was published in 2013 by Eerdmans and is reviewed on this site because of its importance. The Internet and continued availability of books via publisher stock, digital versions, on demand printing, and the online used book market, warrants, in my opinion, reviews of older books of abiding value.

Barry Waugh