While attending Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, Matthew Parker (1504-1575) became interested in the teachings of the Reformation and was a friend of two of its proponents, Thomas Bilney and Hugh Latimer. The reputed local hangout for advocates of Luther’s doctrine was the White Horse Tavern which received the nickname Little Germany. Included with Parker and his friends were another future Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, and avid Luther proponent Robert Barnes. Cambridge was important to the success of the Reformation in Great Britain due to the early Lutheran influences upon the students. Parker completed his studies, was ordained a priest, and then served in different positions until appointed in 1535 to a short-lived chaplaincy to Ann Boleyn (executed 1536). Unlike some others, Parker managed to survive the reign of Roman Catholic Mary I to become Archbishop of Canterbury shortly after Elizabeth ascended the throne in 1558. However, Parker’s friend Bilney had been burned at the stake in 1531 and their colleague, Latimer, also suffered death by fire but at the hands of Mary in 1555. Parker oversaw the Church of England until he passed away in 1575 enjoying the blessing of the Psalm’s three-score-and-ten years (90:10). Archbishop Parker survived because he was politically astute when it came to the affairs of state, and theologically, he compromised by adopting the via media or middle way between Roman Catholicism and Puritan teaching.

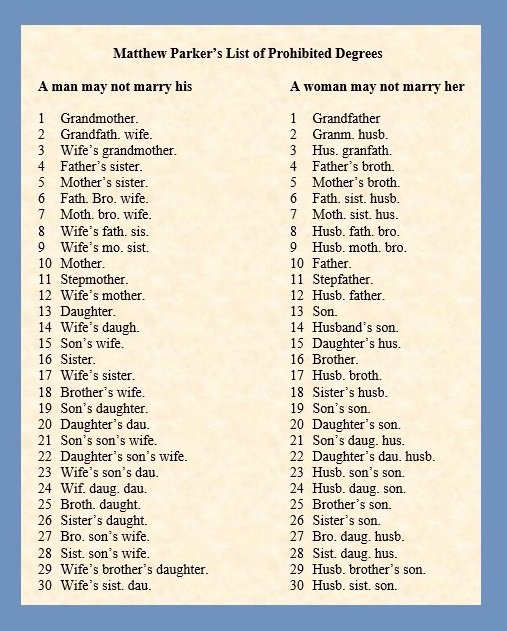

During Archbishop Parker’s tenure he was often involved in religious issues between the monarch and Puritans, but as leader of the Church of England other matters of less renown also required his attention. One such issue involved enforcing the Bible’s prohibition of marriages of consanguinity and affinity. John Strype said of Parker that he was deeply concerned about the abundance of lawless and incestuous marriages in his time. In 1563, he distributed An Admonition to all such as Shall Intend hereafter to enter the State of Matrimony, Godly and agreeable to Laws. The document was an affirmation of the Bible’s teaching and provided a list of prohibited degrees of marriage, that is the kinship relationships if united in wedlock would violate God’s law. The table was to be posted in every church and when bishops visited churches for inspection, they were to make sure the table was publicly posted. It may be difficult to imagine today but individuals marrying their kin was a big problem in the sixteenth century.

The Archbishop of Canterbury was a busy man but he found time to minister to a couple involved in an incestuous marriage. The following excerpt is taken from a letter written by Archbishop Parker to Sir William Cecil (1520-1598), August 9, 1569. Cecil studied at St. John’s College, Cambridge, participated in duties of state in the Elizabethan court, and led the group in charge of protecting the queen from plots. It is interesting that Parker confided in such a spiritual-pastoral matter to one as politically savvy as Cecil, but the two enjoyed a close relationship and Sir William was an important influence for Parker becoming Archbishop.

I am at this day occupied with all the wits I have, to persuade Gerard Danet and his sister-german, that their contracting for man and wife, and having had two children between them, and she now great with the third, that it is sin to be repented of. Thus, the devil locketh up men’s hearts in outrage. Before God, I know not what to do with them, and how to deal. I would I had your counsel. I examine as secretly as I can, and yet it is abroad. I have spent a whole afternoon with the sister, but all is vain. They have continued this ten or twelve years. Six years ago I thought I had won the brother in secret communication from his lewdness, and so he promised me, but it falleth out otherwise. I marvel of their mother. Thus this watchman the devil watcheth and wandereth, etc., to shame God’s word, to shame their house, etc.

The word german means in the context Danet’s blood sister. A brother and sister married and had children. The meaning of german can be interpreted as either full or half brother and sister. John Strype in his Life and Acts of Matthew Parker says the Danets had the same mother but different fathers. Whether it was a full or half-blood relationship, Pastor Parker was clearly distressed. Note that the senior leader of the Church of England had been working with the couple for at least six years and recently “spent a whole afternoon with the sister.” Even though he was a very busy man with the dangers of politics and intrigue ever looming, Pastor Parker was deeply concerned about the Danets. Strype says the Danets’ mother supported the marriage, and Parker’s comment, “I marvel of their mother,” could go either way—she was aghast at what her children had done, or as Strype says, she fully supported it. Parker does not say it in his letter, but the only resolution was for the Danets to repent and separate because this was the policy of the Church of England as defined by Scripture. Note that they were officially married because of “their contracting for man and wife.” They were not only cohabiting but doing so legally. Charles Hodge commented when a near-kin marriage came before the Presbyterian Church in the 1840s that Scripture is clear, the nearer the kin relationship the greater the sinfulness of a marriage; marriages of blood are worse than those by affinity and in both cases the more distant the relationship of the two married, the less the sin.

So, here is a question for contemplation by those of presbyterian polity. A man and woman with two children and one on the way attend the church’s inquirers class, they do not miss a lesson, and they want to unite with the congregation. All appears to be as it should. The time for session interviews comes along and the couple are seated with smiling and hopeful faces. After chit chat, an elder breaks the silence to begin more formally the examination and asks, “How did you two meet?” The wife says, “Oh, Gerard and I met at home; we are brother and sister.” Hopefully, the couple is seeking membership on profession of faith and not by transfer from another church. After the elders pick their jaws up from the floor, what do they do next?

Barry Waugh

Notes—Using the White Horse Tavern, or Inn, for an informal location for teaching Luther’s works is disputed by David Daniell in William Tyndale: A Biography, Yale, 1994, pages 49-50, and others. Several years ago I did what I could with secondary sources to seek good historical background for the White Horse, but much of the information is from John Fox (i.e. Acts and Monuments, known as Book of Martyrs by people today), which has good information mixed with questionable material in some places. Maybe the attraction of the story is the image of a bunch of young divinity student rebels from the local U sitting at a table gorging themselves with pork and downing tankards of ale while they debated the solas of the Reformation. The site of the non-extant White Horse is marked by a blue historical sign.

The letter from Parker to Cecil is on pages 353-54 of Correspondence of Matthew Parker, D.D., Archbishop of Canterbury…From A.D. 1535 to His Death, A.D. 1575, Parker Society, Cambridge University Press, 1853.

For information regarding how the table of forbidden marriages relates to the marriage ceremony of the Church of England, read on this site “Reformation 500th, The Royal Wedding, 2011.”

For Charles Hodge’s comments on a case of near-kin marriage in American Presbyterian History, read The History of a Confessional Sentence, available in PDF on the Log College Press website.