John Holt was born July 23, 1818 in Petersburg, Virginia, the first son of Martha Alexander and Benjamin Holt Rice. At the time his father was pastor of the recently established Tabb Street Presbyterian Church. His mother was the younger sister of founding professor of Princeton Seminary, Archibald Alexander. Newly born John was named for his paternal uncle John Holt Rice. His preparatory education was accomplished in Mount Pleasant Institute in Amherst, Massachusetts, under the instruction of Francis Fellows and Chauncey Colton; the Washington Institute in New York as directed by Rev. J. D. Wickham; and then privately with John S. Hart, LL.D., in Princeton. Following the completion of his undergraduate and law studies in the College of New Jersey in 1841, John practiced law in Richmond for about two years during which time he attended First Presbyterian Church where he professed his faith in Christ during the ministry of William Swan Plumer. He returned to the familiar village of Princeton to study in its seminary where he completed his divinity program in 1845. His six-years junior brother, Archibald Alexander Rice (1824-1902), had completed his seminary education the previous year.

John Holt was born July 23, 1818 in Petersburg, Virginia, the first son of Martha Alexander and Benjamin Holt Rice. At the time his father was pastor of the recently established Tabb Street Presbyterian Church. His mother was the younger sister of founding professor of Princeton Seminary, Archibald Alexander. Newly born John was named for his paternal uncle John Holt Rice. His preparatory education was accomplished in Mount Pleasant Institute in Amherst, Massachusetts, under the instruction of Francis Fellows and Chauncey Colton; the Washington Institute in New York as directed by Rev. J. D. Wickham; and then privately with John S. Hart, LL.D., in Princeton. Following the completion of his undergraduate and law studies in the College of New Jersey in 1841, John practiced law in Richmond for about two years during which time he attended First Presbyterian Church where he professed his faith in Christ during the ministry of William Swan Plumer. He returned to the familiar village of Princeton to study in its seminary where he completed his divinity program in 1845. His six-years junior brother, Archibald Alexander Rice (1824-1902), had completed his seminary education the previous year.

John was licensed by New Brunswick Presbytery, April 23, 1845, and then remained in Princeton to assist his father in his pastoral ministry to the First Presbyterian Church for about a year. After a short ministry as a city missionary to the poor in New Orleans, he was ordained April 30, 1848 for a call to the First Presbyterian Church in Tallahassee, Florida, where he married Lizzie Bogart Neil October 24, 1849. Her father, William, was stated supply in the Iamonia Church which was located north of Tallahassee near the state line. For his next call, Rice returned to his home state of Virginia to pastor the Charlotte Court House Church until 1855, which was followed by a brief term as the agent for the Presbyterian Board of Publication in Kentucky and Tennessee. Louisville, Kentucky, was his next ministry where he shepherded the Walnut Street Presbyterian Church until shortly after the start of the Civil War. The remainder of his life included numerous one to three-year tenures as stated supply in churches in Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee, but from 1867-1868, he was the installed pastor of Third Presbyterian Church in Mobile where he also edited the Presbyterian Index.

August 23, 1878, John Holt Rice responded to a letter from William E. Schenck in which he had asked Rice why he did not fill out and return the Princeton Seminary biographical questionnaire he sent to him. Schenck was responsible for collecting information from Princetonians to publish a catalog. Rice addressed Schenck as his “dear brother and old friend,” as he mentioned their times at the seminary. He said he had not returned the form because he believed…

…it was of no consequence to anybody in the world that my name should be in your catalogue, and I did not believe that any one would be interested in the few facts that might be stated with reference to my ministerial life.

Schenck’s letter had mentioned that all seminarians were to be included in the catalog. Rice had saved the form, so he filled it out and included it with his letter to Schenck. The letter is written on nearly seven full sides of stationery and it includes recollections of the varied ministerial works he had done over the years along with some personal information. He was unable to provide many dates and other material because when he served the Walnut Street Church in Louisville his books and records were confiscated by the the United States District Court. He commented “under what law this was done I have never been able to discover.” The tone of the letter as Rice related events and locations to Schenck is one of despondency. His recollections presented the picture of a life and ministry that had been varied, difficult, and often short on funds with all his memories having their focus sharpened by his recent sixtieth birthday reminding him of what had been, and possibly, what might have been. Maybe he suffered from what the Victorians called melancholia—what would be called depression today.

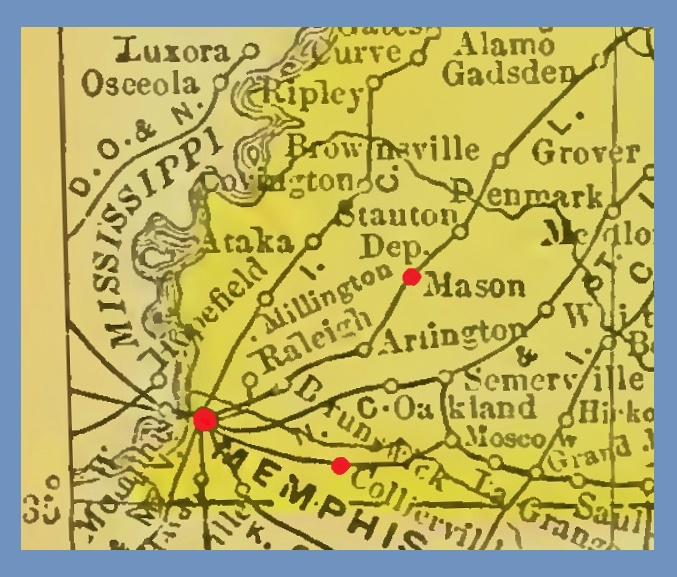

Dr. Rice, preached the Word twice in Collierville, Tennessee, on Sunday, September 1, 1878, contracted yellow fever on Wednesday, and then died of the horrendous disease on Saturday, September 7, 1878, in his home in Mason. Yellow fever deaths had begun in Memphis in mid August. Lizzie was the only one to attend to him as his condition degraded and he passed away. William Schenck had written a response to Rice’s sad letter the same day Rice died. Surely, Schenck would have composed for his old classmate some words of encouragement that would have been welcomed by Rice if he had survived. Because of the yellow fever there was no one willing to take his remains to the cemetery, so John Holt Rice was buried in the backyard of his home under the shade of a tree. Lizzie and a friend of hers had prepared his body for burial. Lizzie’s father led the family and handful of friends and reluctant pallbearers in prayer. Whatever the reasons for Pastor Rice’s difficulties over the years, his life is a reminder that ministers sometimes serve with not only the responsibilities of their congregations and families but also bearing other concerns and fears. Whether Rice’s varied ministerial data sheet could be attributed to interpersonal reasons, distractions from extended family or friends, or circumstances beyond his control—he was faithful to the end as is indicated by his having preached the Lord’s Day before his passing. The trip from Mason to Collierville to supply the pulpit of a church with twenty communicant members may very well have exposed him to yellow fever and ended his life.

Dr. Rice, preached the Word twice in Collierville, Tennessee, on Sunday, September 1, 1878, contracted yellow fever on Wednesday, and then died of the horrendous disease on Saturday, September 7, 1878, in his home in Mason. Yellow fever deaths had begun in Memphis in mid August. Lizzie was the only one to attend to him as his condition degraded and he passed away. William Schenck had written a response to Rice’s sad letter the same day Rice died. Surely, Schenck would have composed for his old classmate some words of encouragement that would have been welcomed by Rice if he had survived. Because of the yellow fever there was no one willing to take his remains to the cemetery, so John Holt Rice was buried in the backyard of his home under the shade of a tree. Lizzie and a friend of hers had prepared his body for burial. Lizzie’s father led the family and handful of friends and reluctant pallbearers in prayer. Whatever the reasons for Pastor Rice’s difficulties over the years, his life is a reminder that ministers sometimes serve with not only the responsibilities of their congregations and families but also bearing other concerns and fears. Whether Rice’s varied ministerial data sheet could be attributed to interpersonal reasons, distractions from extended family or friends, or circumstances beyond his control—he was faithful to the end as is indicated by his having preached the Lord’s Day before his passing. The trip from Mason to Collierville to supply the pulpit of a church with twenty communicant members may very well have exposed him to yellow fever and ended his life.

John and Lizzie had nine children, of which six were alive at the time of his death—two boys and four girls. The boys were named John Holt and Douglas Neil. A reliable source for the girls’ names was not found. Rice had been honored with the Doctor of Divinity by Centre College in Kentucky, 1860, and he had published two articles in the Southern Presbyterian Review, “The Princeton Review on the State of the Country,” 14:1, April 1861, and “The Science of Pastoral Theology,” 17:3, Nov. 1866.

Barry Waugh

Notes—According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the incubation period for yellow fever is three to six days. The portrait of Rice was provided by Wayne Sparkman of the PCA Historical Center in St. Louis; Rice’s age at the time the photograph was made is not known. Newspaper clippings, the letter to Schenck, and other items were provided by Ken Henke of Special Collections, Princeton Theological Seminary. The book on Internet Archive, A History of the Yellow Fever: The Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1878, in Memphis, Tenn., Memphis: Printed for the Howard Association, 1879, provides considerable information about the epidemic and an extensive chronology of yellow fever events in the United States. The online Tennessee Encyclopedia posted by the Tennessee Historical Society has a nicely done article on the yellow fever epidemics in Tennessee, “Yellow Fever Epidemics.” The biography of George D. Armstrong, 1813-1899, on Presbyterians of the Past tells about his experiences with the yellow fever epidemic in Norfolk, Virginia, in 1855. Other information was obtained from the Princeton Seminary necrological reports. The map section is from the map of Tennessee in Rand, McNally & Co.’s Pocket Atlas of the World, 1906, on Internet Archive. A good historical fiction book about an Episcopal minister in Memphis during the 1878 yellow fever epidemic is The Celebrant, 1982, by Charles Turner.