If you have not read the previous articles of this series you may want to do so by visiting the first part, “J. Gresham Machen, France 1918,” and then continuing through the succeeding parts using the links at their ends.

If you have not read the previous articles of this series you may want to do so by visiting the first part, “J. Gresham Machen, France 1918,” and then continuing through the succeeding parts using the links at their ends.

After serving two-hundred-forty-nine cups of hot chocolate on Easter Sunday, the area around Machen’s hut was shelled resulting in his locating refuge in a shelter in a church basement. The days rolled one into another while he continued his hut duties which involved primarily mixing increasing amounts of hot chocolate. The coming of spring brought the color and newness of violets and other flora to the grayness and devastation defining the war zone. Not only were there wild flowers, but Machen obtained some seeds and planted a small flower garden around a patch of grass by the hut. He found that his brief encounters with troops while they bought items in the hut were not conducive to serious conversation. However, Machen was able to speak about the gospel with one French soldier conversing with him to improve his facility with English.

Helping in the hut was a Frenchman named Montí who Machen described as hardworking, congenial, and a good player of the French version of checkers. He also helped Machen with his French by patiently listening to him and correcting pronunciation as well as editing his reports to the YMCA administration. Montí took on more and more responsibility for hot chocolate production and other hut duties, which allowed Machen to mingle with the soldiers.

One of the services provided by a hut director was overseeing a library of books which included only titles that had been approved by the YMCA. Soldiers would sometimes ask Machen questions about the content of selections available which resulted in an occasional conversation of substance. On one occasion a French translation of some of Edgar A. Poe’s works was discussed. One aspect of the library that frustrated Machen was that books supporting Christianity were excluded from the acceptable selections, but on the other hand, books clearly against the Gospel were deemed suitable by the YMCA administration. Note here that the letter “C” in YMCA begins the word “Christian.” The YMCA was established to provide young men transplanted from rural homes to industrialized cities with access to Bible studies and wholesome influences in the midst of many temptations. Machen did not mention it in his correspondence, but a handbook for YMCA speakers noted that no speech should “ask any of you men to change your faith. The YMCA seeks only to help you to live up to your own faith.” Interdenominational organizations inevitably discover that increased inclusiveness is achieved only through decreased doctrinal distinctions.

By the last week of May, the business of the hut had dwindled to nearly nothing. Because of the warmer weather, hot cocoa became ambient chocolate in an attempt to alleviate some of the above-normal temperatures experienced in France at the time. Rats had been a continuing problem for Machen. Given the chocolate, sugar, and other ingredients for the drinks, rodents inevitably found their way into the store of goodies to enjoy a feast. Machen declared war on the intrusive critters and managed to catch seven during the first three nights he used traps. But soon the trouble with the rats would be exchanged for a considerably more serious problem with the Germans.

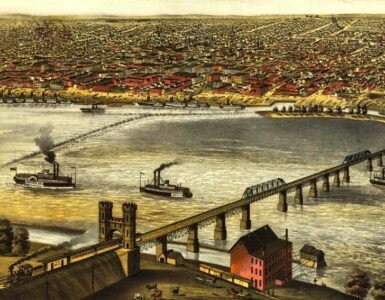

Sunday afternoon May 26, 1918 was a lovely day, but late in the afternoon a general alert was called instructing Machen and Montí to pack everything up and be ready to move out when so ordered. A heavy bombardment commenced with German shells hitting all around and there was an attack with poisonous gas. The next morning the Germans advanced rapidly. The order was given to move out, so Machen joined the exodus across the bridge hoping to make it before the Germans could cut off access. Once on the other side he found shelter from the intense bombardment that was taking place. When the shelling let up he continued his journey away from the front and at one point paused to look back at the battle where smoke was billowing while the Germans continued their destructive advance. Finally, he arrived at a train station and boarded the last train bound for Paris. On May 30th, he commented, “Good bye to all my things, the Boches have swept over my post.”

When Machen had left Paris to begin his work with the soldiers at the front, he commented that residents of the great city were living their lives as if there was no war. Upon his return to the city, much seemed the same.

The town is being bombarded again, but everything goes on just as unconcernedly as before. The city presents the same busy, bright, normal appearance as at the time of my last visit.

Even though Paris was threatened by the German “grosse Bertha,” an artillery weapon that fired a large shell from a great distance, Parisians continued to try and live as though the Germans were not rattling the gates. However, Machen observed that despite the appearance of normalcy, food restrictions were “much more severe”—including on many days no sugar, no butter (particularly difficult for French cuisine), and no meat.

Machen’s letter of May 30, 1918 draws to its end with some poignant observations.

The scenes that I have stressed can never be forgotten, but it is not so easy to make any one else realize what they were like. The refugees, I think, constituted the saddest part of all. The roads for miles and miles were crowded with the wagons containing household effects placed on them in direst confusion. On the train by which I arrived at Paris there was a middle-aged woman with an aged man—utterly infirm—who she told me was her grandfather! I helped with the bundles and got an employee of the station to look out for the party. On arrival, it must be said, the government authorities are doing everything in the world for the unfortunate people. But it is terribly sad.

Tragically, war would not be war without sadness, however memories of its unremitting sorrow encourage—as it would with Machen—resorting to its horrors only after diplomacy and other peaceful means have failed to bring resolution.

BARRY WAUGH

To continue on to part 4, click HERE.

The quotations, except for the YMCA publication mentioned, are from Letters from the Front: J. Gresham Machen’s Correspondence from World War I, 2012.