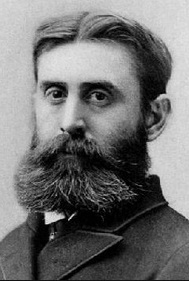

Tuesday, February 16, will be the centennial of the death of B. B. Warfield. His passing left a sizeable gap in the Princeton Seminary line defending the Bible and historic Reformed confessionalism against the German higher critical approach to Scripture and the associated influences of theologians claiming to have the essence of Christianity without the supernatural atoning work of the resurrected Son of God. Warfield was the man for the time and his work continues to be influential. In remembrance of his life and ministry I have turned to what I believe was Warfield’s first love for study, the New Testament. He taught New Testament in Western Seminary before moving to Princeton and continued to read and write about the New Testament even though he was Charles Hodge Professor of Didactic and Polemic Theology (systematics).

Tuesday, February 16, will be the centennial of the death of B. B. Warfield. His passing left a sizeable gap in the Princeton Seminary line defending the Bible and historic Reformed confessionalism against the German higher critical approach to Scripture and the associated influences of theologians claiming to have the essence of Christianity without the supernatural atoning work of the resurrected Son of God. Warfield was the man for the time and his work continues to be influential. In remembrance of his life and ministry I have turned to what I believe was Warfield’s first love for study, the New Testament. He taught New Testament in Western Seminary before moving to Princeton and continued to read and write about the New Testament even though he was Charles Hodge Professor of Didactic and Polemic Theology (systematics).

The short piece that follows has been transcribed from the “Contributions and Comments” section of the August 1920 issue of The Expository Times and it appears to be Warfield’s last explicitly New Testament publication. The Times was published in Edinburgh by its founder and editor James Hastings (1852-1922) who was a minister of the United Free Church of Scotland. In addition to the serial work, he edited Dictionary of the Bible, 5 volumes (1898-1904); Dictionary of Christ and the Gospels, 2 volumes (1906-1908); Dictionary of the Apostolic Church in two volumes (1915-1918); and the massive twelve-volume Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics (1908-1921). He retired from pastoral ministry in 1911 to dedicate his time fully to editing.

The works Warfield refers to in the article were published in German. The language was so much a part of his thinking that sometimes when writing English he slipped into capitalizing all nouns as is done in German. In the academic theological universe of Warfield’s era, German was as necessary as Latin was during the Protestant Reformation.

Notice the mention of psychology and ego as Austrian Sigmund Freud was having increasing influence with his theories regarding psychoanalysis.

Charles Hodge, said this about Paul buffeting his body in his commentary on First Corinthians.

The body, as in part the seat and organ of sin, is used for our whole sinful nature. Rom. 8, 13. It was not merely his sensual nature that Paul endeavored to bring into subjection, but all the evil propensities and passions of his heart.

As will be seen, Warfield not only disagreed with the German theologians, but also his mentor and predecessor for whom his professorship was named.

Some of the article is difficult to follow and a few words have been added in brackets for clarification, but the last paragraph summarizes his interpretation. The text issues in the piece likely result from Hastings having trouble deciphering Warfield’s sometimes cryptic scrawl.

Barry Waugh

Paul’s Buffeting of his Body, 1 Cor. 9:26-27

There is a tendency among the commentators on 1 Corinthians 9:26-27 to deflect it from the official to a more personal application than Paul had in mind. Thus, for example, Hans Windisch (Taufe und Sünde, p. 136) wishes us to see in these verses an intimation that Paul [was] required to keep under [control] his bodily passions—or, as Windisch expresses it, “the temptations to sin which arise from the body”—lest he should be led by them into sin. Accordingly, he generalizes from them: “In the body of the Christian there moves a sinful power, according to this confession, which the Christian distinguishes from his ego, and which he seeks, with all the energy which his ego can exert, to prevent from coming into action.”

Windisch is much nearer right in an earlier remark to the effect that “this self-characterization stands in relation to Paul’s calling as a teacher”; although he applies this remark wrongly. The apostle appears, in point of fact, merely to be alluding in these works to the hardships to which he voluntarily subjected himself in preaching to the Corinthians. Others ate and drank and married; he not only denied himself these common rights of man, but labored without charge, not even taking the gleanings by the way secured by the law to the very laboring oxen and bringing himself into nothing less than bondage to all. It was thus that he buffeted his body, not that he might overcome its evil impulses, but that by its bondage he might the better prosecute his labors. It was not that he feared his body’s passions, but that he was consumed by zeal for the work of the gospel. When he says, “Lest I myself should be rejected,” he but repeats his “Woe is me, if I preach not the gospel.” We learn nothing, therefore, from this passage of the Apostle’s consciousness of sin, or of “the psychology of the sinless man.” What we learn is the strenuousness of the Apostle’s labors in the gospel, and his subordination of the comforts, and even the necessities, of personal life to its prosecution.

Windisch is quite right in rejecting the remark of Max Meyer (Der Apostel Paulus, p. 26), to the effect that the passage shows us the great role which “sin” played in the life of the Apostle, as well as the more generalized one of A. Titius (Seligkeit, iii, p. 81), to the effect that it enables us to observe the degree of power which “sin” still possesses in the believer. But the ground on which he rejects them is not appealing. The Apostle, says he, presents himself as a constant victor; and impulses to sin constantly repressed are not sin. It is quite true, in itself, that “the natural tendencies to sinful movements remain in Christians.” But it is not of them that this passage speaks. The natural tendencies which the Apostle here represents himself as crushing out were not only in themselves lawful, but their gratification would have been lawful. He was, for his work’s sake, denying himself legitimate satisfactions of legitimate bodily needs.

We are far from learning from this passage that “the Christian is distinguished from the heathen by his conscious thinking and conduct being uninfluenced by his concupiscence—by being sinless.” What the passage teaches is that Paul, in the matter of the satisfaction of his bodily needs, denied himself, for his work’s sake, above other Christians. The contrast is between himself and other Christian workers; not between the Christian and the heathen. And the contrast between the Christian and the heathen which is attributed to the passage, so misunderstood, would not be possible on Paul’s lips. The conscious activities of the Christian are not thought of by him as cut loose from his underlying natural movements of impulse. The underlying natural movements of impulse of the Christian are not thought of by him as unaffected by his salvation. With him as with his Lord, the tree is made good that its fruit may be good; his very instincts he expects to be sanctified. So far as his activities were good, they were in his view good, not because they were unaffected by, but because in conflict with them they overcame, inward impulses which, being yielded to, would have made them evil.

B. B. Warfield

Princeton Theological Seminary

Notes: A brief biography of B. B. Warfield is available on this site. The header of the 1 Corinthians 9:26-27 passage is from, The Bible: That is, the Holy Scriptures Conteined in the Olde and New Testament: Translated According to the Ebrew and Greeke, and conferred with the best translations in divers languages. With most profitable Annotations upon all the hard places, and other things of great importance. London: Deputies of Christopher Barker, Printer to the Queenes most excellent Maiestie, 1595; the title is spelled as in the original.