Not too long ago we pulled up to our home after a morning at church and went to the entrance as usual. On the porch was a brown package complete with the usual abundance of bar coded slick paper and Times New Roman font. We knew what it was. We had ordered a coffee maker to replace the one that died a particularly pungent death when the heating coil burned out. As I stood there with tie and jacket in hand, I thought, “What is this doing here? The United States Post Office does not deliver packages on Sunday.” But it seems that it does, which was a factor not taken into account when the new brew maker was ordered a few days earlier. The box on the porch prodded my memory regarding a substantial controversy from the past between Christians and the U. S Postal Service.

Not too long ago we pulled up to our home after a morning at church and went to the entrance as usual. On the porch was a brown package complete with the usual abundance of bar coded slick paper and Times New Roman font. We knew what it was. We had ordered a coffee maker to replace the one that died a particularly pungent death when the heating coil burned out. As I stood there with tie and jacket in hand, I thought, “What is this doing here? The United States Post Office does not deliver packages on Sunday.” But it seems that it does, which was a factor not taken into account when the new brew maker was ordered a few days earlier. The box on the porch prodded my memory regarding a substantial controversy from the past between Christians and the U. S Postal Service.

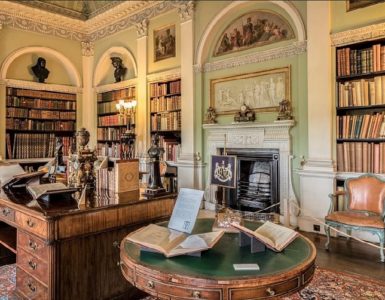

Mail delivery on the Sabbath was an issue that first came before the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA) in 1810. Mr. Wiley, the postmaster in Washington, Pennsylvania, was appealing the decision of the Synod of Pittsburgh excluding him from “the special privileges of the Church” because he worked on the Sabbath and supported mail delivery on that day. He was disciplined by the Synod for Sabbath breaking. Mr. Wiley’s appeal was denied and the decision of the synod was affirmed.

In 1812, Sabbath mail again appeared on the docket of the assembly. The commissioners sent a petition to the United States Congress concerning the “evils of Sabbath profanation,” and it called for changing the national law “relative to the mails as will prevent the profanation of the Sabbath which now takes place in conveying and opening the mail.” Also that year, Postmaster Wiley’s case returned to the assembly via a “petition signed by a number of persons in Washington, Pennsylvania, and its vicinity” desiring the overturn of the 1810 Assembly’s decision because he was such a fine and exemplary citizen. The assembly refused to overturn its judgment and reiterated its reasons for its decision. Then, in 1814, the action of the assembly two years before regarding petitions to Congress had been fruitless because the assembly moved that “each Presbytery [be] directed to take order that the same be circulated for subscription in all the congregations under their care, and forwarded to Congress by the first day of January next.” With apparent failure again in 1814, the 1815 assembly sent another petition.

The undersigned, inhabitants of __________, and State of __________, beg leave to represent to the honorable Senate and House of Representatives of the United States, in Congress assembled, that in the opinion of your petitioners, the transportation and opening of the mail on the Sabbath day is inconsistent with the proper observance of that sacred day, injurious to the morals of the nation, and provoked the judgments of the Ruler of nations. We perceive from the report of the Postmaster General, at your last session on this subject, that it is his opinion that when peace shall arrive [i.e. when The War of 1812 ends], the necessity of carrying and opening the mail on the Sabbath day will greatly diminish. While, therefore, we congratulate you on the return of peace, we approach you with confidence, and beseech you to take this subject into your serious consideration, and enact such laws as you in your wisdom may deem necessary for the removal of this evil. And we, your petitioners, as in duty bound, will ever pray.

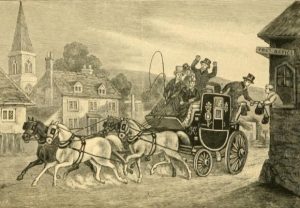

Assembly actions reminding the government and congregations not to break the Sabbath continued to be delivered by the Presbyterian Church for several years. In 1819, the assembly considered an overture concerning reception of a person into the church who owned and operated on the Sabbath a fleet of stage coaches that not only transported passengers but also mail. The assembly said the following about the case.

That it is the decided opinion of this Assembly that all attention to worldly concerns on the Lord’s day, farther than the works of necessity and mercy demand, is inconsistent both with the letter and spirit of the fourth commandment; and consequently all engagements in regard to secular occupations on the Lord’s day, with a view to secure worldly advantages, are to be considered inconsistent with Christian character, and that those who are concerned in such engagements ought not to be admitted into the communion of the Church while they continue in the same.

That it is the decided opinion of this Assembly that all attention to worldly concerns on the Lord’s day, farther than the works of necessity and mercy demand, is inconsistent both with the letter and spirit of the fourth commandment; and consequently all engagements in regard to secular occupations on the Lord’s day, with a view to secure worldly advantages, are to be considered inconsistent with Christian character, and that those who are concerned in such engagements ought not to be admitted into the communion of the Church while they continue in the same.

The subject appeared again in 1826, then 1828, then an extensive multi-point resolution was adopted in 1836 just before the division of the denomination into Old and New Schools. Shortly thereafter the Old School Assembly adopted a long resolution that included another condemnation of Sabbath mail. In 1840 there was more instruction to the churches about the Lord’s Day which included the appointment of a committee of nine members to “correspond with other evangelical denominations on the subject of measures for promoting a better observance of the Lord’s Day.” Moore’s digest notes that similar actions were repeated in 1840, 1843, and 1846. Then in 1853, a general resolution regarding the Sabbath without specific mention of mail delivery ended with a summary paragraph.

While, therefore, we earnestly entreat our fellow-citizens of every class to “remember the Sabbath day to keep it holy,” the Assembly do hereby, in a special manner, enjoin it upon the church Sessions to watch over their brethren with tenderness and great fidelity in respect to the observance of the Sabbath; and to exercise wholesome discipline on those who, by travelling or other ways, presume to trample upon this sacred institution. And we further enjoin it upon the Presbyteries annually to institute inquiries of the eldership, as to the manner in which this injunction has been attended to in their respective churches.

After the Civil War ended Sabbath mail carrying debates continued as the United States continued to provide seven-day mail delivery. In some locations mail was not only delivered on Sunday but sometimes more than once. Due to the closing of nearly all other businesses on the Lord’s Day, private businesses in smaller communities were often contracted to include post offices —sometimes saloons—which were also gathering places for socializing on Sunday. Late in the nineteenth century and into the twentieth the Christian denominations, including the Presbyterians, were active regarding the use of the Lord’s Day. There were interdenominational and denominational Sabbath day preservation societies. For Presbyterians, their sessions, presbyteries, synods, and general assemblies often passed resolutions rebuking congregants for lack of Sabbath reverence while entreating the government to remember the day. When special events like the United States Centennial in 1876, World’s Colombian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, or the St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904 were open seven days a week, Presbyterians were reminded not to attend them on the Sabbath. For several years Presbyterian general assemblies had an annual sermon on keeping the Sabbath.

So, when did Sunday, the Lord’s Day, or Sabbath mail services cease? It was not until 1912 during the presidency of William Howard Taft. The Sunday mail issue came before the House of Representatives in H. R. 21279, which was the appropriations bill for the Postal Service budget through June 30, 1913. After some debate concerning the use of bill riders, finagling the rules, and raising points of order, the resolution was adopted by the House, and then approved by the Senate after a conference with the House about some amendments. Then it was finally signed by President Taft. The part of the bill germane to the issue of Sunday mail is section 5.

So, when did Sunday, the Lord’s Day, or Sabbath mail services cease? It was not until 1912 during the presidency of William Howard Taft. The Sunday mail issue came before the House of Representatives in H. R. 21279, which was the appropriations bill for the Postal Service budget through June 30, 1913. After some debate concerning the use of bill riders, finagling the rules, and raising points of order, the resolution was adopted by the House, and then approved by the Senate after a conference with the House about some amendments. Then it was finally signed by President Taft. The part of the bill germane to the issue of Sunday mail is section 5.

That on and after July 1 next following the passage of this act, letter carriers in the City Delivery Service and clerks in first and second class post offices shall be required to work not more than eight hours a day: provided, that the eight hours of service shall not extend over a longer period than ten consecutive hours, and the schedules of duty of the employees shall be regulated accordingly.

That in cases of emergency, or if the needs of the service require, letter carriers in the City Delivery Service and clerks in first and second class post offices can be required to work in excess of eight hours a day, and for such additional services they shall be paid extra in proportion to their salaries as fixed by law.

That should the needs of the service require the employment on Sunday of letter carriers in the City Delivery Service and clerks in first and second class post offices, the employees who are required and ordered to perform Sunday work shall be allowed compensatory time on one of the six days following the Sunday on which they performed such service.

Churches that had repeatedly pointed out to the government the problem of Sabbath mail for over a century had finally achieved their end, but was it Christian protest or something else that achieved the goal? It seems the end or limitation of Sunday mail is attributable to the rise of organized labor unions and shorter work hours. National legislators had been hearing for years from churches regarding Sabbath mail, but with the rise of unions and better defined hours for workers—two birds could be killed with one stone. Thus, if Sunday is pulled out of the work week the potential regular hours workers can labor have already been reduced by one seventh, which is what the Lord had in mind with the Sabbath. The bonus for the lawmakers was that the Presbyterians and other denominations would stop their protest campaigns about the Lord’s Day. For the legislators, as might be said today, it was “a definite win-win situation.” It was great politics with maybe a touch of piety for the Christians in the national legislature.

The Apostle Paul wrote in Romans 8:7,8, that, “the carnal mind is enmity against God: for it is not subject to the law of God, neither indeed can be. So then they that are in the flesh cannot please God.” The church bears the sword of the Word of God, while the state bears the sword of government. The ministry of the church is spiritual and eternal; the ministry of the state—it is a ministry ordained by God—is physical and temporal. Yes, the church should judiciously address grievous sinful legislation and actions by the state, but it should also know when to cease while continuing to pray for change. The state bears responsibility for its own sins within its physical and temporal domain, just as the church bears responsibility for its sins within its spiritual and eternal realm.

Barry Waugh

Notes—Header image by Frank Magdelyns from Pixabay. The first stamp is U. S. Postmaster, Benjamin Franklin, and the second is a portrait of George Washington; they were issued in 1847 and the images are from Wikimedia Commons. The book referred to above as “Moore’s digest” is, The Presbyterian Digest of 1898, A Compend of the Acts, Decisions, and Deliverances, of the General Presbytery, General Synod, and General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America 1706-1897, compiled by William E. Moore and published in Philadelphia by the Presbyterian Board of Education and Sabbath School Work, 1898; digests were also published in earlier and later editions. The excerpt from the H. R. 21279 was pulled from a secondary source titled, The Postal Record, Edward J. Cantrell, editor, 25:5, May 1912.