The terms Old School and New School are commonly found in articles on Presbyterians of the Past and in American church history in general. The following article provides brief definitions and some background information.

Old School—The Old School believed—in a stricter or fuller subscription to the Westminster Confession of Faith and its associated standards; that the issue of slavery was a political and not a church issue; that missionary work should be under the direct oversight of the Presbyterian Church and not through independent mission organizations; and that the Plan of Union of 1801 affiliating the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA) and the Congregational Church had been detrimental to the Presbyterians because of some of the theological views and practices from New England. These are not all the points of disagreement but they cover most of the issues. It could be said that the Old School believed—the church should be directly ruled in all its ministries by elders connectionally associated through its sessions, presbyteries, synods, and general assembly, with its interpretation of the Word of God governed by a conservative, full subscription, use of the Westminster Standards, and it believed that the church’s ministry is exclusively spiritual and not political. Thus, the Old School had a strong sense of the Word’s warrant for presbyterian church government and it held to the necessity of confessional standards for proper interpretation of the Bible for governing the church rightly in its spiritual ministry.

New School—The New School believed that subscription to the Westminster Confession of Faith involved little or no commitment to its doctrine; the issue of slavery was within the bounds of the spiritual ministry of the church and many thought that immediate abolition was the best solution; the use of what might be called today interdenominational mission organizations was beneficial and more efficient for missionary work and church extension than committees overseen directly by the presbyters; the Plan of Union had helped both the Congregationalists and the Presbyterians, particularly in the growth of both denominations in the western frontier (i.e. New York, Ohio, etc.); and the New England theology had influenced the PCUSA to be less rigorous and more open to differing doctrinal ideas. The New School views could be summarized—the Presbyterian Church is governed by elders locally and by connectional relationship among its congregations, but other polities, including congregational, are scriptural as well; the Presbyterians should participate in missionary organizations that are not under direct control of the denomination for more efficient evangelism; the interpretation of the Word of God by the Westminster Confession is of lesser or no importance for church doctrine and practice; and the church’s ministry is spiritual, but the spiritual work does not exclude political activism for what the church sees as pervasive sins in society. Thus, the New School had a lesser sense of the uniqueness of presbyterian ecclesiology and a more inclusive idea of denominational ministry; a liberal, or nonexistent, adherence to the confessional standards for doctrine; and an expanded idea of what the spiritual ministry of the church looks like.

If you have never read anything about the Old School and the New School before you may be thinking that the two could not continue to exist together because it was a tenuous relationship at best. You would be correct. An earlier division then reunion of Presbyterians had occurred in the mid-eighteenth century which included some similar issues. The point that brought the issues of contention into focus was the Plan of Union with the Congregational Churches accomplished in 1801 for the purpose of joint work in some ministries, especially missions. It was not a union that made the Congregationalists into Presbyterians, but instead it was a limited agreement to be united in certain aspects of their work. Opposition to the Plan of Union followed several routes but the main contention against the Plan of Union was based on the influence of what is termed the New England Theology or Hopkinsianism. Samuel Hopkins (1721-1803) was a Congregational minister in Rhode Island and a key proponent of the theology, but the designation Hopkinsian included other theologians such as Nathanael Emmons (1745-1840) and Edwards Amasa Park (1808-1900). As the years passed, the members of the respective schools found their points of difference more polarizing, especially as the issue of slavery sectionalized both the nation and the churches. At the 1837 General Assembly the Old School had a majority and was able to undo some of the affects of the Plan of Union, break the relationship with the Congregationalists, and eject the New School synods. Obviously, it was not a happy situation following the 1837 assembly. The press, both private and religious, reported some of the less than dignified moments on the floor of the assembly as commissioners debated while the moderator and others called for calmness.

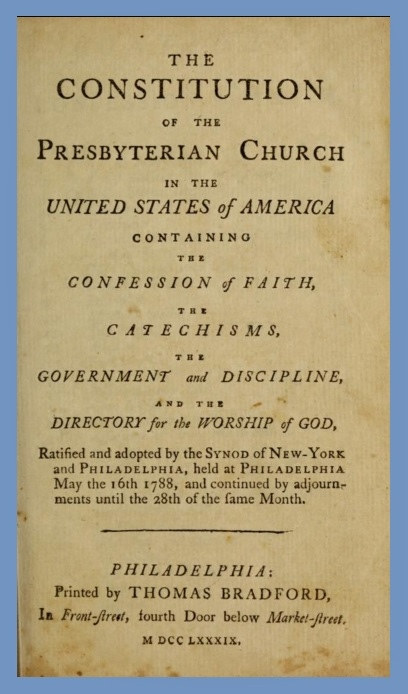

When the Old School General Assembly met the next year in Philadelphia in Central Presbyterian Church, the New School attempted to join in the proceedings but had to leave for another church for its sessions. An examination of the title pages of the published assembly minutes of the schools shows that each believed itself the true PCUSA. A rule-of-thumb way of distinguishing which school published the minutes and many of their other publications is by reading the place of publication on the title pages–Philadelphia was used by the Old School and New York by the New School.

The Old School lost a substantial number of churches to the Presbyterian Church in the Confederate States of America (PCCSA) in 1861 as a result of the Gardiner Spring Resolutions concerning allegiance to the Federal government and issues associated with the Civil War. Commissioners from the South and some in the North contended that Spring’s resolutions were placing a political requirement upon them for membership in the church. During the war, the PCCSA, reunited with the fairly small number of New School churches in the Confederacy. The Old and New schools of the PCUSA reunited in 1869. The PCCSA changed its name to Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS) in 1865 and it reunited with the PCUSA in 1983.

Barry Waugh

The header shows the Westminster Assembly as in a print provided courtesy of Reformation Art.