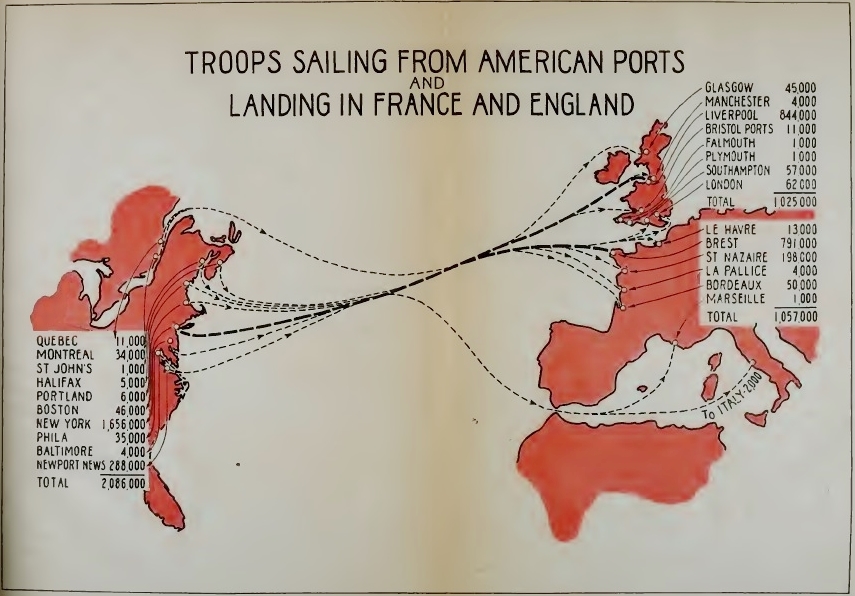

At seven in the morning of the sixteenth of January one-hundred years ago today, J. Gresham Machen set sail from New York for the purpose of providing United States troops with spiritual counsel and gospel witness while working in support services with the Young Men’s Christian Association in France. The interdenominational YMCA was not his first choice for work as a noncombatant. He could not become a chaplain for the Presbyterian Church because the positions filled quickly, then he hoped to drive an ambulance but chose not do so because they could be commandeered to carry ordnance. Thus, as did many ministers of the day, he resolved to do his bit for the war effort as a “Y-man” supporting the American Expeditionary Force.

At seven in the morning of the sixteenth of January one-hundred years ago today, J. Gresham Machen set sail from New York for the purpose of providing United States troops with spiritual counsel and gospel witness while working in support services with the Young Men’s Christian Association in France. The interdenominational YMCA was not his first choice for work as a noncombatant. He could not become a chaplain for the Presbyterian Church because the positions filled quickly, then he hoped to drive an ambulance but chose not do so because they could be commandeered to carry ordnance. Thus, as did many ministers of the day, he resolved to do his bit for the war effort as a “Y-man” supporting the American Expeditionary Force.

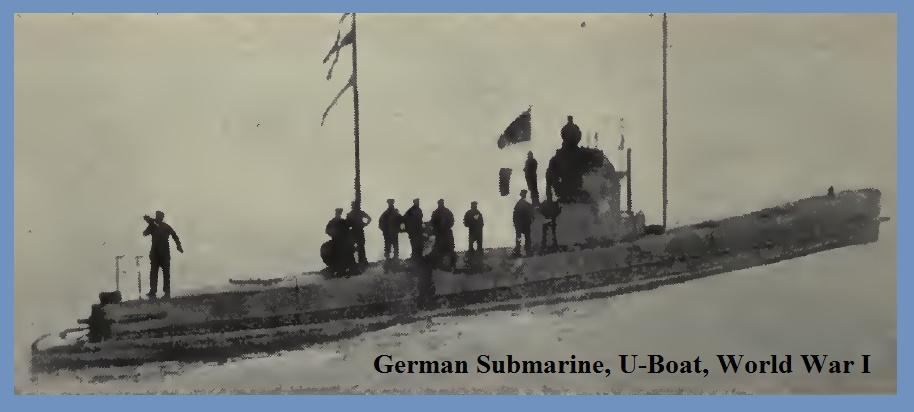

The book, Letters from the Front: J. Gresham Machen’s Correspondence from World War 1, 2012, includes letters he sent home with the lion’s share destined for his mother in Baltimore. The first letter in the collection provides a summary account of his journey for the eleven days ending on January 25, 1918. On board ship Machen roomed with two other YMCA men in a stateroom amidships on the first deck, which was a good location for minimizing the affects of rough seas. The journey started out well and appeared to be no different to Machen than a peace-time Atlantic sailing. Temperate weather, a glassy sea, and neatly folded blankets on the deck chairs all contributed to hopes for an uneventful journey. There was really little indication that the ship was bound to the war zone. But that evening as twilight turned to night, the situation changed as precautionary measures were taken to protect the ship. Every source that could provide the slightest sliver of light was masked in order to blend the ship into the darkness and hide it from the monocular view of German U-boat periscopes. Also, there were two guns on board—one at the bow and the other astern. This trip was very different from Machen’s previous transatlantic journeys.

The sea is a particularly unpredictable element of God’s creation and as the ship advanced along its route, the monster that is the Atlantic Ocean snarled regularly. The winds increased and the waves billowed. As the sea churned into white-caps, Machen became pale with nausea, but as he put it, he “made no contribution to the fishes.” While in bed one night a metal pitcher tottered from its perch due to the rolling ship and fell on his head. The unsettled Atlantic smoothed for a time, but then on Sunday it became even rougher than before because “a strong wind and sea sprang up” resulting in the ship “continuing a healthy roll.” Despite the tempestuous weather and Machen’s queasiness he was able to teach a brief lesson during the Sunday worship service. He commented regarding the singing of How Firm a Foundation while the ship rolled that “We needed that hymn.” Likely Horatio Spafford’s It is Well with My Soul would have also suited the situation.

The sea is a particularly unpredictable element of God’s creation and as the ship advanced along its route, the monster that is the Atlantic Ocean snarled regularly. The winds increased and the waves billowed. As the sea churned into white-caps, Machen became pale with nausea, but as he put it, he “made no contribution to the fishes.” While in bed one night a metal pitcher tottered from its perch due to the rolling ship and fell on his head. The unsettled Atlantic smoothed for a time, but then on Sunday it became even rougher than before because “a strong wind and sea sprang up” resulting in the ship “continuing a healthy roll.” Despite the tempestuous weather and Machen’s queasiness he was able to teach a brief lesson during the Sunday worship service. He commented regarding the singing of How Firm a Foundation while the ship rolled that “We needed that hymn.” Likely Horatio Spafford’s It is Well with My Soul would have also suited the situation.

J. Gresham Machen taught New Testament in Princeton Seminary, so study, education, and language interests were in his blood. While at sea he took advantage of the French lessons provided for passengers. He did not think he was progressing as he should in acquiring the Gallic tongue, but others told him that he was doing quite well. Since his work in France would be with American troops he believed that opportunities to learn parler français more fluently would be limited. French prose and conversation were challenging enough for Machen, but he was particularly frustrated by a lecture on board ship in which the teacher read French poetry selections. He commented poetically, “a most discouraging feature to me, since I get very little of the poetry.” On Monday, while the seas continued to billow, he delivered a lecture to some of the YMCA men titled, “Christianity and the World Crisis,” in which he traced briefly the state of New Testament scholarship at the time. It was a subject he had studied thoroughly and one which would find expression after the war in The Origin of Paul’s Religion, 1921, and The Virgin Birth of Christ, 1930, along with other publications.

As the ship neared its port in France, Machen said that it was passing through the area where German submarines were most active. Some of the passengers slept on the deck fully clothed so they would be ready to quickly access the lifeboats if a torpedo struck the ship. He commented that “there seems to be no real expectation of seeing a submarine,” but that did not stop him from sleeping partially dressed in his street clothes. Machen’s twenty-seven-page hand-written letter ended—

As the ship neared its port in France, Machen said that it was passing through the area where German submarines were most active. Some of the passengers slept on the deck fully clothed so they would be ready to quickly access the lifeboats if a torpedo struck the ship. He commented that “there seems to be no real expectation of seeing a submarine,” but that did not stop him from sleeping partially dressed in his street clothes. Machen’s twenty-seven-page hand-written letter ended—

I have plenty of five-franc notes, but they are too big to give a porter. We hope to get the Saturday morning train to Paris. It is pretty nearly time to mail the letters; so I say good bye for the present and send lots of care to all.

In conclusion, the remembrance of the First World War has been limited in the United States. Cable television channels a few years ago were running some very good serial accounts of the war, but they must not have been very well received because they have dwindled in frequency. Books have been published and both CSPAN and PBS have had their commemorative programs, but honestly, the abundant carnage, chemical warfare, disfigurements, deaths, and rampant disease are hard to take. War is always horrid, but it was shockingly so when it began in Europe because much of the continent had been experiencing prosperity and optimism until the firing of a few fatal shots in Sarajevo. President Woodrow Wilson had struggled to keep the nation out of war. As a child he had seen in Augusta, Georgia, a multitude of dead and groaning wounded Confederate soldiers while living in the manse of First Presbyterian Church. It was no wonder he wanted to keep the nation out of war, he knew the costs. However, added to his childhood Civil War experiences was a progressivist optimism that drove his public pacifism. The Great War killed Progressivism, seeded the flappers and promiscuity of the Lost Generation, and brewed a pessimism not only about peace but more importantly about life itself. Could it be that the limited remembrance of the First World War is because the optimism, alliances, and prosperity that preceded it strike too close to home as the global economy and its rising stock values produce a similar way of thinking? However, today, if a few shots are fired their significance will not initially be measured by the death of a royal couple, but will instead likely be seen in the killing of a multitude.

In addition to more posts about J. Gresham Machen’s experience during the war, the centennial will be remembered on Presbyterians of the Past with other items about Presbyterian and Reformed subjects of relevance. The post preceding this one, John Wesley Ischy, 1885-1973, tells the story of a chaplain serving in France, and other chaplains’ biographies will be added as the year progresses. Readers are referred to other entries regarding the war including Chaplain T. M. Bulla and aviator Lt. J. V. Wilson along with other posts. The articles “J. Gresham Machen, The Great War,” and “Over There, Presbyterians in the First World War,” offer background information and a PDF version of a pocket-size Presbyterian worship book published for distribution to members of the military. A few articles will include American Christianity’s thinking about the war and the influence of eschatology on that thinking.

Barry Waugh

To continue on to part 2, click HERE.