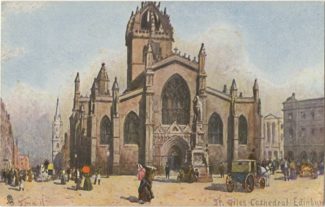

It might be thought that one as important to the history of Presbyterians and Scotland as John Knox would have a distinguished place of burial. It would hopefully be a pleasant statue, or a nice monument with some information about him. But no, the approximate site of his grave is designated with a square white stone and a descriptive slab set in asphalt. John Knox is awaiting the resurrection beneath parking space number twenty-three in Parliament Square behind St. Giles Cathedral in Edinburgh. Maybe those who paved over the remains of Knox and his deceased colleagues were skeptical descendants of the anti-supernatural Sadducees. Regardless, if you want to see the burial site of John Knox you will have to stand on blacktop instead of a green church yard lawn.

It might be thought that one as important to the history of Presbyterians and Scotland as John Knox would have a distinguished place of burial. It would hopefully be a pleasant statue, or a nice monument with some information about him. But no, the approximate site of his grave is designated with a square white stone and a descriptive slab set in asphalt. John Knox is awaiting the resurrection beneath parking space number twenty-three in Parliament Square behind St. Giles Cathedral in Edinburgh. Maybe those who paved over the remains of Knox and his deceased colleagues were skeptical descendants of the anti-supernatural Sadducees. Regardless, if you want to see the burial site of John Knox you will have to stand on blacktop instead of a green church yard lawn.

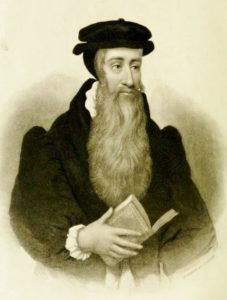

John Knox was born in 1514 near Haddington which is about eighteen miles east of Edinburgh. The climate of the village is sufficiently temperate that it was known in its day for orchards. His father, William, was a freeman and may have been a merchant or craftsman, and what is known about his mother is that her maiden name was Sinclair. After completing his studies in the grammar school in Haddington, Knox was taught by the scholastic theologian and historian John Major at St. Andrews University. He finished studies and was ordained a priest by Bishop of Dunblane William Chisholm, April 1, 1536. Even though lads of the day often aspired to be priests, Scotland had too many and obtaining a benefice was difficult. Apparently the grim prospects for ministry came to fruition for Knox because by 1540 he was a notary apostolic in Haddington and practicing law. Four years later Notary Knox was living in the household of Sir Hugh Douglas of Longniddry for the purpose of tutoring his two sons.

John Knox was born in 1514 near Haddington which is about eighteen miles east of Edinburgh. The climate of the village is sufficiently temperate that it was known in its day for orchards. His father, William, was a freeman and may have been a merchant or craftsman, and what is known about his mother is that her maiden name was Sinclair. After completing his studies in the grammar school in Haddington, Knox was taught by the scholastic theologian and historian John Major at St. Andrews University. He finished studies and was ordained a priest by Bishop of Dunblane William Chisholm, April 1, 1536. Even though lads of the day often aspired to be priests, Scotland had too many and obtaining a benefice was difficult. Apparently the grim prospects for ministry came to fruition for Knox because by 1540 he was a notary apostolic in Haddington and practicing law. Four years later Notary Knox was living in the household of Sir Hugh Douglas of Longniddry for the purpose of tutoring his two sons.

Knox was converted to Christ through the effort of Thomas Guillaume and was influenced to turn from John Major’s scholasticism through reading Augustine and other church fathers. In 1545 he was first influenced by the sermons of George Wishart. Wishart, a fellow Scot, had been on the Continent absorbing the doctrines of Luther and Calvin until he returned to Scotland. Knox worked with Wishart until he was arrested, convicted of heresy for his Protestant teaching, and burned at the stake in 1546. Knox was well known to be a colleague of Wishart and when Cardinal Beaton was murdered in May, the situation became more fearsome for Knox. In April of the next year Knox and his students sought refuge in the Castle of St. Andrews with the hope of avoiding agents of the papacy seeking him for heresy. He continued his teaching and ministry of the Word in relative freedom behind the castle walls until French galleys entered St. Andrews Bay, laid siege to the castle, and severely breached the wall with cannon fire which resulted in the inhabitants surrendering. Knox and over a hundred other those captured were condemned to row in the galleys. He survived nineteen months of brutal existence as a galley slave until his release in 1549.

The year 1549 was one of optimism for Protestants in England because with the death of politic-Protestant Henry VIII, his nine-year-old son Edward VI became king and his accession brought hope that the Reformation teaching given to him by his tutors would result in a truly Protestant England. It is believed that John Knox’s release from the French galley was accomplished through Edward’s influence. Knox went to England and was soon appointed to serve a church in Berwick-upon-Tweed, which is barely in England from Scotland on the North Sea coast. However, he was there only a year or so until he was moved to Newcastle following a confrontation in Berwick with the ecclesiastical authorities over his condemnation of the Mass. He also ministered in other churches and was one of the chaplains serving Edward VI. Young King Edward’s reforming rule ended with his passing on July 6, 1553. His successor was Roman Catholic Queen Mary. Reformers had enjoyed a brief golden era under Edward, but Mary’s accession made it advisable for any leader even remotely interested in reform to leave England, including Knox. The initial fears of England’s Protestants were confirmed by the mass of executions by “Bloody Mary” as she removed vestiges of the Reformation from her country.

The year 1549 was one of optimism for Protestants in England because with the death of politic-Protestant Henry VIII, his nine-year-old son Edward VI became king and his accession brought hope that the Reformation teaching given to him by his tutors would result in a truly Protestant England. It is believed that John Knox’s release from the French galley was accomplished through Edward’s influence. Knox went to England and was soon appointed to serve a church in Berwick-upon-Tweed, which is barely in England from Scotland on the North Sea coast. However, he was there only a year or so until he was moved to Newcastle following a confrontation in Berwick with the ecclesiastical authorities over his condemnation of the Mass. He also ministered in other churches and was one of the chaplains serving Edward VI. Young King Edward’s reforming rule ended with his passing on July 6, 1553. His successor was Roman Catholic Queen Mary. Reformers had enjoyed a brief golden era under Edward, but Mary’s accession made it advisable for any leader even remotely interested in reform to leave England, including Knox. The initial fears of England’s Protestants were confirmed by the mass of executions by “Bloody Mary” as she removed vestiges of the Reformation from her country.

Knox took refuge for a time in Dieppe on the English Channel northwest of Paris until he traveled to Geneva and joined other exiles seeking the teaching of John Calvin. He did not stay long initially because he received a call from the English refugee church in Frankfurt am Main which was located about three-hundred miles north of Geneva in Germany. Reluctantly, he consented to the call because of encouragement from Calvin, but due to conflict over the congregation’s worship liturgy and what Knox described as “popish practices,” he returned to Geneva. From 1555-1559, Knox learned from Calvin in conjunction with his ministry to the English congregation. He made a return trip to Scotland during the time but after a brief visit he returned to Geneva for his safety.

Knox took refuge for a time in Dieppe on the English Channel northwest of Paris until he traveled to Geneva and joined other exiles seeking the teaching of John Calvin. He did not stay long initially because he received a call from the English refugee church in Frankfurt am Main which was located about three-hundred miles north of Geneva in Germany. Reluctantly, he consented to the call because of encouragement from Calvin, but due to conflict over the congregation’s worship liturgy and what Knox described as “popish practices,” he returned to Geneva. From 1555-1559, Knox learned from Calvin in conjunction with his ministry to the English congregation. He made a return trip to Scotland during the time but after a brief visit he returned to Geneva for his safety.

During Knox’s sojourn by scenic Lake Geneva he composed a treatise for which he is commonly remembered. In 1558, The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women was published. The use of Monstrous Regiment does not mean women marching in formation as armed troops in a war against men, but instead refers to what Knox believed was “unnatural rule” by women. The Blast contended that women rulers were contrary to Scripture and natural law. The tract was offensive to many, including John Calvin, and was absolutely odious to Catholic Queen Mary of England and Catholic Queen of Scotland, Mary of Guise. When Protestant Elizabeth became queen of England in 1558, Knox showed no favors to her Protestantism but instead wrote a defense of Blast addressed directly to her.

With the accession of Elizabeth most of’ Knox’s refugee English congregation left Switzerland to return to England, however Knox could not join them because Elizabeth’s hatred of him led to his exclusion from the land. He sailed instead directly to Scotland in May 1559 with the encouragement of Protestant lords and continued to be a vocal leader in the movement for reform. Following conflict between Catholics and Protestants in Scotland, Mary Queen of Scots returned to Edinburgh from France in 1561 and continued her personal Catholic practices while keeping a watchful eye of reluctant tolerance towards the Scottish Kirk. Mary’s reign was often a struggle between Catholic, Protestant, and political interests in which Knox often participated through print and sermons leading to confrontation with the authorities for his views. Mary was eventually forced to abdicate resulting in her toddler, James, succeeding her. John Knox preached the coronation sermon for wee James. James VI ruled Scotland beginning in 1567, he added the throne of England as James I in 1603, with both reigns ended by his death in 1625. Despite baptism as a Catholic, James became a Protestant and was particularly important for English speakers due to the Bible published in 1611 known as the King James Version. However, despite her loss of rule, Mary did not just fade away like an old soldier but rather continued intrigue, manipulation, plotting, and deception as she maneuvered to improve her royal position. In desperation she made the suicidal decision to flee to England where Queen Elizabeth had her executed February 8, 1587 after an extended imprisonment. The period during which John Knox worked for reform in Scotland was one of political instability complicated by the continuing tension between Protestants and Catholics.

What is currently called St. Giles Cathedral began as the simple parish church of St. Giles in medieval Edinburgh, and the present structure dates to the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries with modifications, additions, repairs, and restorations occurring several times over the years. John Knox was the minister of St. Giles’ from 1560 to 1572. As was common during the Reformation, the ornaments, decorations, and altars of Catholicism were removed during his ministry and a substantial pulpit was installed which showed the central importance of the Word for worship . John Knox not only ministered at St. Giles but also continued to be involved in the greater Church of Scotland in many ways with one of his most important contributions being the First Buke of Discipline, 1560, which governed worship and order for the Presbyterians of Scotland. In Buke there is instruction regarding the design of churches and the importance of pulpits, which can be read about on Presbyterians of the Past in the article, “Church Design-Pulpits.”

What is currently called St. Giles Cathedral began as the simple parish church of St. Giles in medieval Edinburgh, and the present structure dates to the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries with modifications, additions, repairs, and restorations occurring several times over the years. John Knox was the minister of St. Giles’ from 1560 to 1572. As was common during the Reformation, the ornaments, decorations, and altars of Catholicism were removed during his ministry and a substantial pulpit was installed which showed the central importance of the Word for worship . John Knox not only ministered at St. Giles but also continued to be involved in the greater Church of Scotland in many ways with one of his most important contributions being the First Buke of Discipline, 1560, which governed worship and order for the Presbyterians of Scotland. In Buke there is instruction regarding the design of churches and the importance of pulpits, which can be read about on Presbyterians of the Past in the article, “Church Design-Pulpits.”

John Knox suffered a stroke in July 1570 which affected at least one of his arms because he referred in his writings to his “dead hand.” He was able to minister on an irregular basis until he left Edinburgh for St. Andrews. He returned to Edinburgh in August 1572 after receiving a letter from a group of congregants requesting his return so “that once again his voice might be heard among them.” He died November 24. Knox had been married twice, first to Marjory Bowes, and the second time to Margaret Stewart Ochiltree. Two sons from Marjory, along with Margaret and three daughters survived him. Like Calvin, he was buried without a marker, which explains the approximation of the location of his remains in the St. Giles churchyard under the parking lot.

Knox’s works are available in the six volumes edited by David Laing titled The Works of John Knox, which were published 1846-1864 and have been reprinted in subsequent years. In Laing’s edition Knox’s History of the Reformation in Scotland is in the first two volumes which provide general history woven with personal aspects of Knox’s life along with transcriptions of primary sources and other material. W. Stanford Reid in his biography Trumpeter of God has defended Knox’s History of the Reformation against those labeling it hagiography saying that “wherever he could, he used original sources, many of which he reproduced” and it “is still a work that no one interested in this area can afford to neglect.”

Barry Waugh

Notes—The National Archives of the UK has an image of a letter by Knox sent to Queen Elizabeth, August 6, 1561. The British Library has some lovely selected scans of pages of Knox’s The First Blast. The complicated history of the rulers of England, France, Spain, and Scotland in the sixteenth century are sometimes difficult to follow due to too many Marys, James, Henrys, and such. In the case of Britain, I have found The Oxford Companion to British History, edited by John Cannon for Oxford University Press, 1997, very helpful with each entry written by university level lecturers or professors. There is likely a later edition, but I have found that with each new edition of such publications there are fewer entries for Christian related subjects.

Sources—The header shows a view of Edinburgh and the postcard image shows St. Giles. Thomas M’Crie (1772-1835), Life of John Knox; Containing Illustrations of the History of the Reformation in Scotland, with Biographical Notices of the Principal Reformers…[etc.], First Complete American Edition, Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1905; M’Crie published his first edition in Edinburgh, 1811. John Knox, by Jasper Ridley, Oxford, 1968, is good, detailed, lengthy, and provides social, geographical, political, and other aspects of Knox’s times. Moving to 1974, as was mentioned earlier, W. Stanford Reid’s, Trumpeter of God: A Biography of John Knox, was published by Charles Scribner’s Sons. An article titled, “John Knox’s Communion Service,” published by The Church Service Society in its Annual number 5 (1932-1933), 15-36, describes an early order for communion as administered by Knox in the church at Berwick-upon-Tweed. A current Knox title which I have yet to receive for reading is John Knox, published by Yale University Press in 2016, which was written by Jane Dawson who is John Laing Professor of Reformation History, School of Divinity, University of Edinburgh.