On Reformation Day, the posting of Martin Luther’s theses on the door of the castle church in Wittenberg is remembered as the event that launched the Protestant Reformation. Luther’s initial intention was to reform Catholicism and not replace it with another church; Luther’s work, at least in the early years, was submissively reforming rather than revolutionary. However, in England, the fruit of reform seeded by Luther’s theses had ripened into a revolution against Rome when Henry VIII renounced papal authority and established himself as the head of the Church of England. Henry abandoned the Catholic Church to achieve a divorce from his first wife, Catherine of Aragon.

Following the death of heir-to-the-throne Prince Arthur in 1502, his father, Henry VII, arranged a marriage between Arthur’s widow, Catherine of Aragon, and Arthur’s brother, Henry, who was the next in line of succession to the throne and Henry VII’s  only surviving son. The proposed union was within the prohibited degrees of marriage as defined by the Roman Catholic Church through its interpretation of the Bible and the church’s canon law. As such, the marriage was judged to be incestuous because Henry would be marrying his deceased brother’s widow. It would be a marriage of affinity—a marriage with one who is kin by marriage, and not one of consanguinity—a marriage with one who is kin by blood. So that the marriage could take place, Pope Julius II granted a bull allowing Henry and widow Catherine to marry in June of 1509. Henry VII had recently died on April 21, which provided an impetus to completing the marriage so Henry VIII would have a queen and they could pursue having a boy to become heir to the throne. As the years passed it became clear to Henry that Catherine was not going to give him the male heir that he so greatly coveted, so he sought a way to end his sonless, but not childless, marriage.

only surviving son. The proposed union was within the prohibited degrees of marriage as defined by the Roman Catholic Church through its interpretation of the Bible and the church’s canon law. As such, the marriage was judged to be incestuous because Henry would be marrying his deceased brother’s widow. It would be a marriage of affinity—a marriage with one who is kin by marriage, and not one of consanguinity—a marriage with one who is kin by blood. So that the marriage could take place, Pope Julius II granted a bull allowing Henry and widow Catherine to marry in June of 1509. Henry VII had recently died on April 21, which provided an impetus to completing the marriage so Henry VIII would have a queen and they could pursue having a boy to become heir to the throne. As the years passed it became clear to Henry that Catherine was not going to give him the male heir that he so greatly coveted, so he sought a way to end his sonless, but not childless, marriage.

As Henry VIII looked for a way to end the marriage, he discovered in Leviticus 20:2 that a man who married his brother’s widow would be cursed with a childless marriage. He believed that he had no son as punishment for marrying Catherine, but the couple was not childless because they had a daughter. However, the use of Leviticus 20:21 for his case became even more apropos in 1527 when a Cambridge Hebrew scholar, Robert Wakefield, told King Henry that the Hebrew of Leviticus said more precisely that the punishment would be the death of sons in particular and not children in general. The evidence for Henry’s understanding of the Leviticus verse was convincing because of the five conceptions achieved by Henry and Catherine, two were miscarriages, two were sons that died within a few weeks of birth, and the only survivor was Princess Mary. One can see how the King would have been impressed by the relevancy of Wakefield’s interpretation as he contemplated his male heir to the throne problem.

The complexities of exegesis and application of the Levitical prohibitions against marriages of affinity are exemplified in Henry’s approach to Rome. As Henry presented his case he based his appeal for terminating his marriage with Catherine on two factors, first, he contended that the union of a man with his brother’s wife was contrary to the Law of God, and secondly, he argued that Pope Julius’s dispensation was invalid. The second point seems a risky approach because Henry VIII was discrediting a previous pope in his appeal to a sitting pope, which seems an unlikely track to success and may explain to some degree the lack of cooperation from Pope Clement VII. However, both of his points showed a Protestant spirit because the first appealed directly to the Law of God over against its interpretation and application by Rome, while the second stated that Pope Julius had erred in giving his bull allowing the marriage.

As Henry sought separation from Catherine, the confrontational method he pursued led to increased opposition from the papacy. However, as it turns out, there was another option he could have tried. One historian, J. J. Scarisbrick, has shown that Henry would have been wise to listen to Catherine’s repeated contention that her marriage to Arthur was not consummated, which would have likely worked in the king’s favor. Henry himself had said that Catherine came to him a virgin—though later, as he developed his case, he said he had been joking. The reason he deemed his comment a joke may have been driven by concern to defend his deceased brother’s adolescent virility because he had married Catherine when he was fifteen and died not long thereafter. However, as Scarisbrick turned to the Catherine and Arthur marriage he pointed out that even though the union was not consummated, it would have been quite something else to establish the legal certainty of non-consummation unless Henry and Catherine came to agreement regarding Arthur’s failure, which was unlikely given Catherine’s opposition to the divorce.

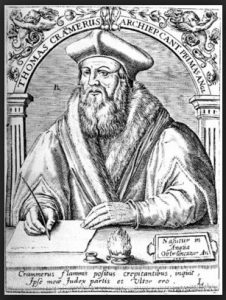

King Henry VIII decided to turn to the scholars of England and the Continent in hopes of finding appropriate grounds for separation that would satisfy Rome. The idea for seeking the opinions had been formulated by Thomas Cranmer when Edward Fox and Stephen Gardiner explained to him that there was an impasse between England and Rome concerning the divorce. The king adopted Cranmer’s idea and canvassing the universities for opinions began in August 1529. Opinions were sought from all academics of any reputation, so much so that the consulting fees paid by King Henry became a secondary source of income for the often meager-salaried scholars. One study of the “Great Matter,” as the Henry-Catherine divorce came to be known, lists twenty-three universities and at least 160 scholars responding to the throne’s request for opinions.

King Henry VIII decided to turn to the scholars of England and the Continent in hopes of finding appropriate grounds for separation that would satisfy Rome. The idea for seeking the opinions had been formulated by Thomas Cranmer when Edward Fox and Stephen Gardiner explained to him that there was an impasse between England and Rome concerning the divorce. The king adopted Cranmer’s idea and canvassing the universities for opinions began in August 1529. Opinions were sought from all academics of any reputation, so much so that the consulting fees paid by King Henry became a secondary source of income for the often meager-salaried scholars. One study of the “Great Matter,” as the Henry-Catherine divorce came to be known, lists twenty-three universities and at least 160 scholars responding to the throne’s request for opinions.

King Henry’s involvement in the literature regarding the ending of his near-kin marriage is seen in his publication of the Censurae, which was later published in English as The Determinations. These tracts from some of the canvassed academics supported Henry’s case to divorce and provided the public with the near-kin opinions of academia. The Universities of Paris, Bourges, Bologna, Padua, Anjou, Toulouse, and Orleans all condemned the marriage as against the laws of God and of nature, and they argued that the Pope’s bull allowing the marriage was a case of his overstepping his authority. Thomas Cranmer’s solicitation of the academic opinions had become a key means to continue the literature in favor of the invalidity of Henry’s marriage and further his quest for its end. Cranmer, who would increasingly become sympathetic to the Reformation, also pursued the opinions of key Protestants.

The opinions that came from the scholars were being gathered by agents of King Henry such as Simon Grynaeus (1493-1541). Grynaeus had entered the Reformation through the influence of Luther, but he eventually grew impatient with Luther’s conservative and slow approach to changing the church. He moved to Basel, came under the influence of Oecolampedius, and began teaching at the University of Basel where he taught until his death. Grynaeus visited England in 1531 where he befriended several Reformation proponents. When he returned to Basel he did so with a secondary income as a solicitor of opinions regarding Henry’s marriage from the scholars of Switzerland, Wittenberg, and Strasburg. In a letter to Henry VIII in the fall of 1531, Simon Grynaeus summarized the views he had retrieved to date. He saw two perspectives on the issue. The first concluded that Henry’s marriage to Catherine was “unlawful” and “it cannot be valid by any prescription of time” and divorce was allowed. The second view admitted the unlawfulness of the near-kin union, but believed it should be permitted to continue if the marriage could be used righteously and the couple had “such strength and firmness of conscience” to continue in their union. Then Grynaeus concluded that both these views saw the marriage as condemned by nature, the “general consent of nations,” and Leviticus. Thus, more data was added to the already complex situation as Henry sought an end to his marriage in his quest for a wife that could bear him a son.

The opinions that came from the scholars were being gathered by agents of King Henry such as Simon Grynaeus (1493-1541). Grynaeus had entered the Reformation through the influence of Luther, but he eventually grew impatient with Luther’s conservative and slow approach to changing the church. He moved to Basel, came under the influence of Oecolampedius, and began teaching at the University of Basel where he taught until his death. Grynaeus visited England in 1531 where he befriended several Reformation proponents. When he returned to Basel he did so with a secondary income as a solicitor of opinions regarding Henry’s marriage from the scholars of Switzerland, Wittenberg, and Strasburg. In a letter to Henry VIII in the fall of 1531, Simon Grynaeus summarized the views he had retrieved to date. He saw two perspectives on the issue. The first concluded that Henry’s marriage to Catherine was “unlawful” and “it cannot be valid by any prescription of time” and divorce was allowed. The second view admitted the unlawfulness of the near-kin union, but believed it should be permitted to continue if the marriage could be used righteously and the couple had “such strength and firmness of conscience” to continue in their union. Then Grynaeus concluded that both these views saw the marriage as condemned by nature, the “general consent of nations,” and Leviticus. Thus, more data was added to the already complex situation as Henry sought an end to his marriage in his quest for a wife that could bear him a son.

All of this wrangling with Rome and canon law as well as canvassing the universities and academics came to naught, because after several years of conflict the matter was to be solved through another means. On May 15, 1532, the King’s document called the Submission of the Clergy was enacted and the clergy were forced to acknowledge King Henry as the Protector and Supreme Head of the Church. The standing archbishop, William Warham, found the submission odious but he followed the king’s desire. Conveniently, for Henry, Warham died shortly after the Submission of the Clergy, which allowed Henry’s man, Thomas Cranmer, to be consecrated the new archbishop on March 30, 1533. Shortly thereafter, May 23, 1533, Archbishop Cranmer announced his judgment ending the marriage between Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon because it was in fact a “pretended marriage” and that they “contracted and consummated the said pretended marriage de facto and not de jure, and that they, so separated and divorced, are absolutely free from all marriage bond.” Henry had already married Anne Boleyn secretly in January of 1533, she was crowned queen in May, and Elizabeth, who would become Queen Elizabeth I, was born to her in September. The complete break with Rome was achieved by Parliament’s Act of Supremacy, October 30, 1534, when Henry VIII was recognized officially as the Supreme Head of the Church of England. Henry’s quest for a male heir led him into the labyrinthine workings of affinity as he sought to justify his divorce from Catherine, but when all was said and done, he obtained the end of the marriage using his power as king to renounce Rome’s authority, establish the Church of England, and have himself as the supreme spiritual authority in the land.

In conclusion, near-kin marriage was the cause of the Tudor throne’s break with Rome and it produced heated debate as the legitimacy of King Henry’s marriage to Catherine was challenged. At least some of the complexity of the situation was due to differing methods for interpreting Mosaic legislation. Henry’s marriage to his deceased brother’s wife was not a peripheral matter; the union addressed issues central to the Reformation including papal authority and sola Scriptura. Despite differing views regarding the legitimacy of Henry’s marriage to Catherine, the marriage was broken by divorce on the basis of it having transgressed Leviticus 18:16, and thus it could be said that the English Reformation’s Ninety-Five Theses event was resolution of the “Great Matter” with the divorce of Catherine and Henry through the establishment of the Church of England with Pope-King Henry VIII as its supreme head.

BY BARRY WAUGH

Sources—J. J. Scarisbrick’s book is, Henry VIII, London: Eyre & Spottiswood, with the discussion of the marriage of Henry and Catherine found in pages 163-197. The book by Guy Bedouelle and Patrick Le Gal, Le “Divorce” Du Roi Henry VIII, Etudes et Documents, Genève: Librairie Droz S.A., 1987, was helpful for information as found on pages 309-437, 445-453, and 469-70. For the text of the divorce tracts published in Latin (Censurae) and English (The Determinations), see, Edward Surtz and Virginia Murphy, eds., forward John Guy, The Divorce Tracts of Henry VIII, Angers: Moreana, 1988. The letter from Grynaeus to Henry VIII, September 10, 1531, was found in Original Letters Relative to the English Reformation, ed. Hastings Robinson, Parker Society series, Cambridge: University Press, 1847, 2:555-56. The quote regarding Cranmer’s pronouncement of the divorce is from page 470, of vol. 6, of The Lives of the Archbishops of Canterbury, by Walter F. Hook, London: Richard Bentley, 1868.