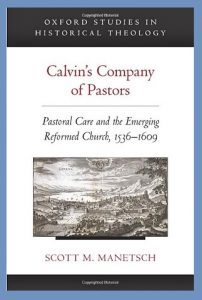

Scott M. Manetsch’s Calvin’s Company of Pastors: Pastoral Care and the Emerging Reformed Church, 1536-1609, Oxford, 2013, paper 2015, presents a lesser known aspect of John Calvin’s life and work. Calvin is not often described in a pastoral context by those who write about his life. For example, Robert Godfrey’s, John Calvin: Pilgrim and Pastor, 2009, and John Calvin: Writings on Pastoral Piety, edited by Elsie Anne McKee, are two of the few pastoral titles available. A survey of Manetsch’s secondary sources in his bibliography shows few titles concerned with pastoral issues, but a glut of titles regarding doctrinal, political, and social subjects. Calvin’s Company of Pastors makes an important contribution to a more panoramic understanding of a brilliant, complex, and dedicated pastor.

Scott M. Manetsch’s Calvin’s Company of Pastors: Pastoral Care and the Emerging Reformed Church, 1536-1609, Oxford, 2013, paper 2015, presents a lesser known aspect of John Calvin’s life and work. Calvin is not often described in a pastoral context by those who write about his life. For example, Robert Godfrey’s, John Calvin: Pilgrim and Pastor, 2009, and John Calvin: Writings on Pastoral Piety, edited by Elsie Anne McKee, are two of the few pastoral titles available. A survey of Manetsch’s secondary sources in his bibliography shows few titles concerned with pastoral issues, but a glut of titles regarding doctrinal, political, and social subjects. Calvin’s Company of Pastors makes an important contribution to a more panoramic understanding of a brilliant, complex, and dedicated pastor.

Dr. Manetsch says of Calvin’s Company of Pastors that its purpose “is to examine the pastoral theology and practical ministry activities of the cadre of men who served as pastors in Geneva’s churches during nearly three-quarters of a century from 1536 to 1609” (2). The study is presented following three themes—first, the religious nature of the Geneva ministers’ idea of vocation; second, he says “it is inaccurate to portray Calvin and his pastoral colleagues as ivory-tower theologians, disengaged from the every day concerns of their parishioners”; and third, he shows that while Theodore Beza and his colleagues guarded the legacy of Calvin, they also made subtle changes to his pastoral paradigm to meet practical challenges (9-10).

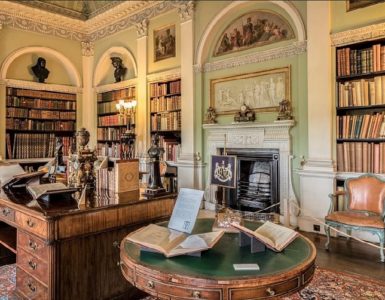

The author’s plan is executed with 307 pages of text divided into nine chapters that are followed by a catalog of biographical vignettes of Geneva’s ministers, notes, a bibliography, and an index. Along with maps of Geneva at the beginning of the book are illustrative tables, lists, and statistical analyses distributed throughout the text to support the author’s presentation. The opening chapter, which is particularly helpful for setting the scene as Calvin first entered Geneva, provides information about how the Reformation unfolded in the city; the next chapter introduces the design and ministry of the Company of Pastors, with the next two chapters providing additional detailed information; chapters 5 and 6 address the nature of ministry in terms of schedules and duties, and the centrality of the ministry of the Word; chapter 7 is titled, “The Ministry of Moral Oversight”; then there is a chapter for bibliophiles titled, “Pastors and Their Books”; and the final chapter describes the pastoral care expected of Geneva’s ministers.

One of John Calvin’s observations regarded church attendance. Before the Ecclesiastical Ordinances of 1541, the people were allowed to go to the temple of their choice—the three churches within the city, St. Pierre, St. Gervais, and St. Germain were called temples. However, Calvin commented that the practice was unacceptable because it fostered the belief that ministers were preachers and not pastors (20). Thus, the Ordinances required both children and adults to attend their parish temples for certain services. Given his observation about sixteenth-century preacher chasers in Geneva, what might Calvin suggest to churches today regarding television, internet, and video preachers?

A brief recounting of the order and practice of worship in Geneva is provided on pages 152-56. It not only describes the simple vernacular liturgy with its use of the Psalms, but also includes some of the problems faced within the churches. For example, the ministers suffered from the malady that perpetually plagues preachers—the failure to preach within a limited period of time. In the case of Geneva, the sermons were restricted to forty-five minutes but continued over runs led to installing hour glasses in the churches with sufficient sand for forty-five minutes. Needless to say, the sixteenth-century hour glass in view of the minister was no more helpful for controlling preachers’ tongues than the clocks opposite pulpits today.

There were some interesting problems in services, especially given the irenic nostalgia with which worship in Calvin’s Geneva is sometimes viewed. Services could be disrupted and noisy. A man took his hunting firearm and dog to church so he could quickly stalk his prey after the service. One of the temples was near a blacksmith’s shop and the noise caused by forging disturbed the services. During a communion service a mentally disturbed woman barked like a dog. A woman used a stool for her weapon to severely injure another woman’s leg during an argument over seating, and another woman insisted on sitting near a particular man because God had told her she was going to marry him (men and women had separate seating). It was not uncommon for congregants to snore loudly, hold conversations, or pass around food during sermons. In conjunction with the description of worship in Geneva, Calvin’s view of preaching and the importance of rhetoric is summarized on pages 156-173.

One assumption made by Dr. Manetsch for his scrutiny of Geneva’s discipline is questionable. On page 199 he says with regard to his statistical analysis of disciplinary cases that the words “suspension and excommunication will be employed as synonyms.” It may be that the sources he used were not clear as to which measure of discipline was applied to individuals, but according to the common interpretation of the disciplinary sequence in Matthew 18:15-20 as illumined by other passages, “suspension” is separation from the Lord’s Supper and “excommunication” is the final step for a congregation member because it means removal from the roll of the church. Excommunication, hopefully, occurred considerably less often than suspension in Geneva.

An example of church discipline which readers might find a bit humorous involves honoring the memory of John Calvin. In 1570—Calvin died in 1564—a man named Claude Griffat was suspended from the Lord’s Supper for naming his dog “Calvin.” There is hopefully more to this story because it appears to be a show of power by the Consistory. If a dog was named “Churchill,” the owner likely intended to honor Sir Winston’s memory. Even though some Genevans would find Griffat’s act offensive, is it something that required suspension from the Lord’s Supper? Should a person be pressed to repent of such a thing? One of the concerns of church discipline is the spiritual welfare of the offender, recovering the wayward, but in Geneva between 1542 and 1609 there were over 9,200 suspensions, which as was noted earlier includes separation from the Lord’s Supper and excommunication. Church discipline is a mark of the church, but it is important to be cautious and conservative with its use.

Throughout the book the author brings out tension between the Consistory and the Company of Pastors. There are several examples given of the Consistory overruling the ministers, such as whether a particular minister could pastor one of the area churches. Geneva in the sixteenth century is generally known today for its disciplinary environment and Dr. Manetsch points out that after Calvin and Beza passed from the scene, an increasing confusion of church and state developed with the state often coming out on top. History has shown that a proper relationship between church and state inevitably deteriorates into state dominance, which is particularly evident in the current condition of state churches established as a result of the Reformation. Even though in Calvin’s era discipline was sometimes intrusive and disturbing by current standards, the positive side included discovering and punishing criminal behavior such as wife abuse, infanticide, beating of children, and brutality to livestock.

There are few subjects regarding Calvin, the Company of Pastors, the Consistory, and Geneva’s churches that are not discussed in Calvin’s Company of Pastors. Scott M. Manetsch has provided a thoroughly researched presentation of the subject that objectively, analytically, critically, and contemplatively illumines the pastoral work of John Calvin and his colleagues in ministry. This book is heartily recommended as essential for anyone interested in John Calvin, Geneva, and the work of the Company of Pastors.

BY BARRY WAUGH

Notes–A biographical subject on Presbyterians of the Past, Rev. Thomas Smyth, D.D. (1808-1873), had a problem with the length of his sermons during the many years he was pastor of Second Presbyterian Church in Charleston, South Carolina.